When the heart is hard and parched up, come upon me with a shower of mercy.

When grace is lost from life, come with a burst of song.

We do not know when Mohandas K. Gandhi first heard Rabindranath Tagore’s song “Jibano jakhono sukaaye jaay” (1910). But we do know, on the testimony of his secretary and alter ego, Mahadev Desai, that it was one of Gandhi’s “favourite songs”. Its opening lines reproduced above, as translated by the poet, may well be the reason why it was so.

Tagore has rendered jibano in the original Bangla as “the heart”. Only he had the authority to change his word-pictures. “Hard” and “parched up” paint a desert scene of the kind Gandhi knew from his childhood in rock-dry Kathiawar. To convert that desiccated terrain into a metaphor for an unfeeling heart would have struck him as only natural. And would have appealed to his inner sensitiveness.

Gandhi had a way of capturing songs, making them part of his mind’s music repertory, so that quite a few songs have come to be known as being ‘one of his favourite songs’. Tagore’s “Ekla chalo re” (1905) has, of course, come to be even more closely associated with Gandhi than “Jibano jakhono”. Indistinguishable from his ‘lonely pilgrimage’ in riot-engulfed East Bengal in 1946, “Ekla chalo” has become twin to another extraordinary work of art from Bengal — Nandalal Bose’s black and white linocut of the “Dandi Gandhi” (April 12, 1930).

To return to “Jibano jakhono”. This song is part of two defining moments in his life. The first belongs to the year 1932. Gandhi is deeply exercised over the British government’s ‘Communal Award’ which, following the Second Round Table Conference held in London in 1931, was a rejection of Gandhi’s plea for not separating “untouchables” or the Depressed Classes from the rest of India’s future electorates. Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, he says, are Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Sikhs for all time. But “untouchability” is a condition, not an identity and one that must, in civilization’s name, go. B.R. Ambedkar differs from Gandhi at the Conference vehemently and successfully, and the Award meets his aspirations. It says the Depressed Classes will have a separate electorate, “untouchables” being elected by “untouchables”; they will not be part of a general electorate.

Back from the Conference in India and, in fact, a prisoner of the raj when the Award is announced, Gandhi sees it as calculated hard-heartedness towards Indian attempts at reform, progress, human dignity. In fact, another callous example of London’s encouragement to the divisions that plague and imprison India. Unless the Award is revised, he says, he would cease taking any food of any kind save water from September 20. And the fast does so begin. The weapon he knows outside that of negotiation — satyagraha through a fast — electrifies the nation. It also does something more important. It brings Ambedkar and Gandhi to a fresh discussion and, even as the fast deepens and upper-caste Hindu orthodoxy is challenged to make new gestures of inclusiveness to “untouchables”, the two leaders reach a historic accord — the Poona Pact which has Gandhi accept reserved seats and Ambedkar accept a common electorate. Gandhi in a statement says he sees “the hand of God” in “the glorious manifestation”.

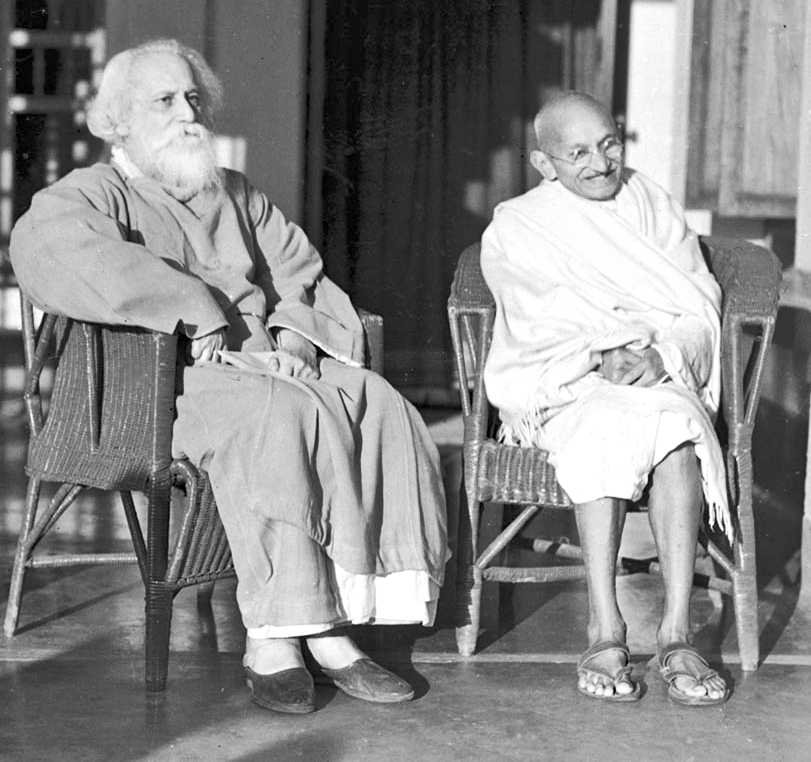

Tagore meanwhile has travelled across the country from Calcutta to Poona to be with the fasting man. On September 26, six days after it started, as the fast is broken and the Pact is signed, Mahadev Desai asks Tagore if he could please sing “Jibano jakhono”, describing it as one of Gandhi’s favourites. Be it that or not, it is curiously appropriate for the occasion which has come as “a shower of mercy”. The principle of reservation of seats through a common electorate is now part of the Indian Constitution’s arrangements for electing India’s representatives in legislatures, a felicity in terms of the numbers of Depressed Classes’ — now Scheduled Castes and Tribes — representation in the halls of law-making. A blow to the raj’s then hard-heartedness and to the parched conscience of Hindu society.

Fifteen years later, Gandhi and India are into another September — that of 1947. And into the other great ‘divide’ in India — Hindu-Muslim. India has been free since August 15, and partitioned into India and Pakistan, exactly as the Muslim League leader, M.A. Jinnah, wants. But the countries are burning. Gandhi, who is in Calcutta, staying in a house chosen by him in the city’s Muslim quarter of Beliaghata, is fasting. He is doing that to bring sanity to the city and to still the frenzy of communal violence. Some brave-hearts are doing all they can to fight the flames. Two youths — Smritish Banerjea and Sachindranath Mitra — are killed as they interpose between rioting mobs from the two communities.

On the fifth day of the fast, Gandhi is feeling its action. He is giddy, exhausted from the starving and the discussion over several hours and, in Hydari Manzil, Beliaghata, begins to utter “Rama Rama”. The prospect is grim. And then it happens.

Chastened by the stark reality of Gandhi’s life being in danger, the city begins to stagger to return to some calm. Leaders of the Hindu Mahasabha and the Muslim League and others from the Sikh community as well, confer among themselves, come to Gandhi and give him an undertaking in writing: “We, the undersigned, promise to Gandhiji that peace and quiet have been restored in Calcutta once again. We shall never again allow communal strife in the city. And shall strive unto death to prevent it.” The statement is read out to Gandhi who then, on September 4, agrees to end the fast which has lasted for seventy-three hours. To the singing of “Jibano jakhono” and the Ramdhun, the former premier of the undivided Province of Bengal and controversialist, H.S. Suhrawardy, gives him the glass of orange juice to end the fast with. As Gandhi sips the fluid, Suhrawardy falls at his feet, weeping.

Tagore has been gone seven years but on that September night of 1947, his song sends a shower of mercy.

And, miracle of miracles, another ‘shower’ happens as well — guns, swords, daggers, cartridges are surrendered that day and the next day to Gandhiji. These are arms some men have used to threaten, maim and murder innocents.

Poona’s Pact and Calcutta’s Promise have been anointed by a song.

Seventy-three years on, the Poona Pact and the Great Calcutta Miracle and that song need to be recalled by an abashed, embarrassed India. On the parched up hardened denial of its guilt, the atonement offered and the undertaking offered to Gandhi by Calcutta, redeemed.