There is hardly any expectation — at least within India — that the reported ‘de-escalation’ of military tensions along the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh’s Galwan Valley that followed the telephonic discussions between the special representatives of India and China last Sunday evening will trigger a return to ‘peace’ and ‘tranquillity’. There are many loose ends that are unattended, not least of which are military perceptions on the ground and levels of political determination. It took nearly seven months of negotiations in 2017, manoeuvres and counter-manoeuvres, for the conflict in Doklam Valley on the India-Bhutan-China border to reach a near-satisfactory level of de-escalation. However, even this ‘truce’ is likely to be extremely fragile. The two sides may not exchange artillery fire along the LAC but Sino-Indian relations are bound to be extremely tense in the near future. For all practical purposes, both India and China have declared each other as hostile neighbours.

The real reasons that prompted the People’s Liberation Army to undertake a fresh bout of incursion along the LAC will, in all likelihood, remain unknown for many decades. However, if one of the principal objectives was to quietly test Indian and global responses — and this seems a periodic exercise — without letting events spiral out of control, Beijing will have much to chew on.

First, it is clear that while shirking from outright military hostilities, the government of Narendra Modi is not inclined to give China the benefit of the doubt — as, arguably, some earlier regimes in India were. India’s border response has been governed by a combination of both firmness and restraint. The willingness to negotiate at the level of local military commanders has been supplemented by the resolute determination to clearly identify the unacceptable. However, unlike earlier times when a ‘forward policy’ was based on military unpreparedness, the Modi government’s firmness has been backed up by India’s enhanced capacity. While assessing the domestic political fallout of the loss of 20 Indian jawans in the skirmish, the Chinese side has been absolutely silent about their own casualties.

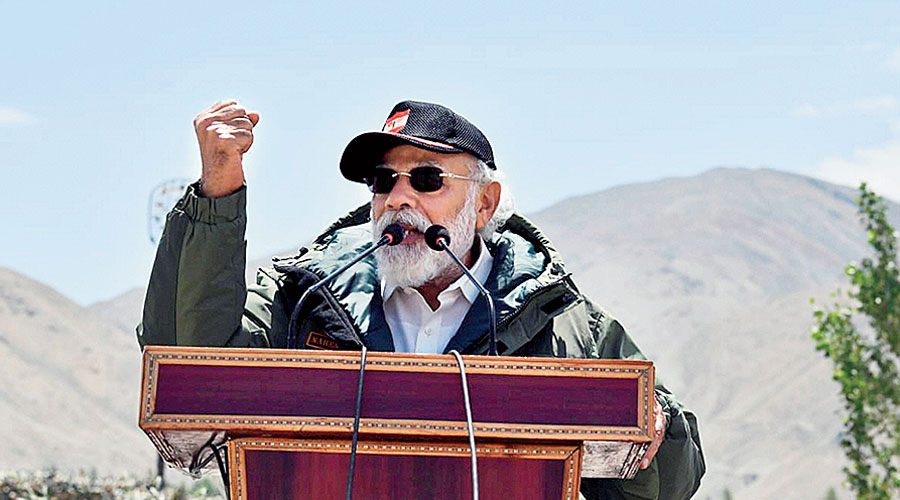

Beijing may also have concluded that far from India getting a bloody nose, the credibility and standing of the Modi government have been largely unaffected. China’s analysts would have noted that the taunts and barbs directed at the Indian prime minister have been confined to exactly the same circles that have been resolutely opposing him since 2014. This is grudgingly conceded by the Western media that — owing to a mixture of unfamiliarity with the saffron dispensation, not to mention its easy proximity to the Delhi liberal ecosystem — is unsparingly hostile towards Prime Minister Modi. Citing a poll by Morning Consult that showed Modi’s approval rating at 74 per cent, a Financial Times report suggested that “Indians’ unshakeable confidence in Mr Modi reflected his almost messianic image as a leader who is seen as eschewing family and personal enrichment to devote himself to public service.” The prime minister’s visit to the Ladakh front line and his speech debunking the “age of expansionism” have further bolstered his pre-existing nationalist credentials. Just as the bus diplomacy with Pakistan failed to affect Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s standing during the Kargil conflict, the inability of Modi’s personal diplomacy with Xi Jinping to yield results hasn’t affected his political standing within India.

Secondly, it is significant that in responding to China’s ‘expansionism’ that involves periodically asserting its claims on territories it sees as parts of Greater China — prior to the ‘century of humiliation’ — the Indian response hasn’t been confined to more effective management of the frontiers. The ongoing programme of infrastructure building and enhancement of military capacity has been supplemented by the opening of a second front — denying China the benefits of a large market in India. The ban on 59 apps of Chinese provenance that jeopardize national security may be a symbolic step. However, in the short term, it is certain to be complemented by restrictions on Chinese companies bidding for contracts and other Chinese investments. The total Chinese investment in the Indian economy is estimated to be at around $8 billion and this cannot be nullified overnight. However, the government is in a position to create an environment that makes it difficult for companies with obvious China links — particularly links that can be traced back to China’s State apparatus — to obtain cumbersome statutory clearances.

Thirdly, it is apparent that hostilities against China on the economic front will not constitute an effective pressure point on China if it is undertaken by India alone. For long, and particularly in the context of the seven-decade dispute with Pakistan over the status of Jammu and Kashmir, India has been wary of internationalizing neighbourhood disputes. Although there have been occasions when India has accepted international mediation — the Soviet Union played a role in ending the India-Pakistan war of 1965 — the desire to keep the country insulated from Big Power rivalries has shaped the allergy towards any international involvement in the neighbourhood. It is unlikely that this principle will be formally repudiated. However, dealing with China is a different ball game altogether. It is worth bearing in mind that with the rapid progress of the China-Pakistan economic corridor that also envisages Afghanistan as its backyard, the encirclement of India will assume a menacing dimension.

It is increasingly apparent that China’s aggressiveness in its border dispute with India cannot be viewed in splendid isolation. There are, of course, China’s designs on what are called the ‘five fingers’ of Tibet — Arunachal Pradesh, Bhutan, Sikkim, Nepal and Aksai Chin-Ladakh. The claims on these regions, either by way of direct incorporation or transformation into tributary states paying obeisance to the Middle Kingdom, are periodically asserted. However, following the incorporation of the Belt and Road scheme into the Constitution of the Communist Party of China in 2017, the military, economic, technological and soft power might of China has been directed towards the creation of a unipolar Asia (and Australia), with China back in its role as the Middle Kingdom. Although the tentacles of this grand and somewhat terrifying vision extend beyond Asia to include strategic control over the economies of Africa and Europe, it is Asia which is in the front line of China’s assertive hegemonism.

China and its fellow travellers have often presented the Belt and Road as a new ‘harmonious world’ and a ‘community of shared destiny’ — its version of the end of history. However, as the Portuguese writer, Bruno Maçães, observed in his seminal work, Belt and Road: A Chinese World Order, “Once a ‘community of shared destiny’ has been advanced as the only correct option, the temptation is to start identifying disharmonious elements, those who, as the Chinese authorities like to put it, still harbour a Cold War mentality or a zero-sum approach to world politics. The implication is that the same Chinese elites who developed the concepts guiding the Belt and Road must now be left to decide how those concepts are to be executed... Participants in the Belt and Road are thus pushed to a position where only two options are possible: agreeing to its basic tenets and goals or declaring oneself on the wrong side of history.”

In not signing up for the Belt and Road, India has declared itself on the wrong side of China’s Mandate of Heaven. Fortunately, it is not the only country that has chosen to uphold the blend of economic progress and national sovereignty. By its defiance of China, it has cast itself as the alternative in Asia and a natural ally of other countries repelled by China’s single-minded, immoral pursuit of hegemonism. The harnessing of this global alliance must become a pillar of India’s national security.