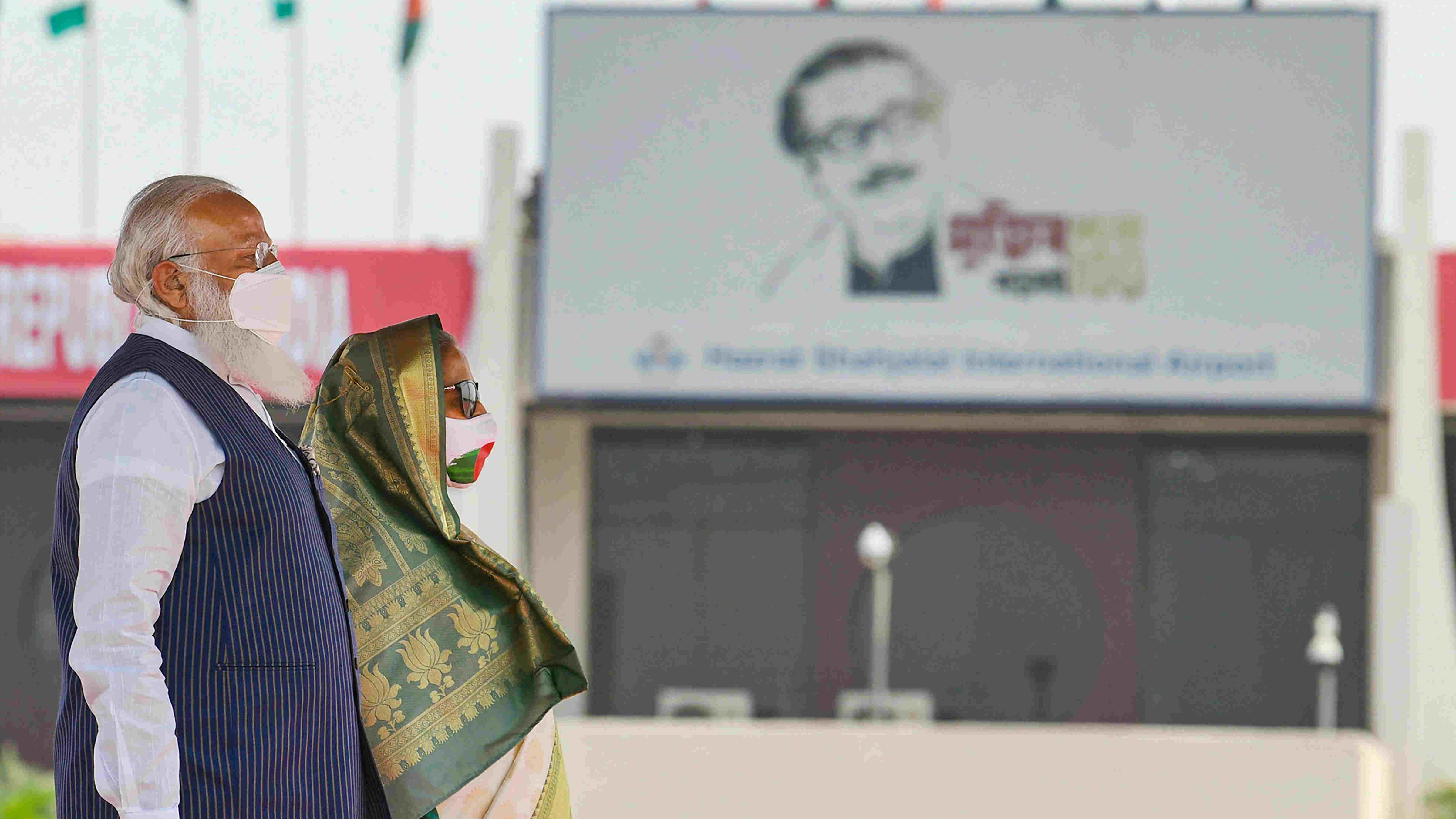

The former prime minister, Manmohan Singh, one of India’s most erudite and perceptive statesmen, had once said that the nation can choose its friends but not its neighbours. In a rare and happy occurrence, New Delhi has in Dhaka a reliable friend as well as an ideal neighbour. That the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, is the guest of honour at the celebrations to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of Bangladesh — it also happens to be the centenary birth year of Bangladesh’s founder, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman — is a testament to the strength as well as the potential of this friendship.

History, of course, has played its part in cementing the bond. India’s contribution to the creation of Bangladesh is truly historic. The political prudence of Indira Gandhi was matched by the valour of India’s armed forces that facilitated Bangladesh’s birth by fire. India has been a model of freedom and democracy for the smaller neighbour that has witnessed periods of turbulence. Present-day India, arguably, could learn a few things from Bangabandhu’s unfailing commitment to secularism as well as from Dhaka’s progress in the economy — that too, in a pandemic year — and in human development indicators. The two nations have marched forward with some of the most significant strides being taken in recent years. In 2015, the leadership of both countries signed the Land Boundary Agreement, facilitating the exchange of enclaves that not only enabled the resettlement of populations on the basis of their choice of residence but also resolved some border issues. Anti-Indian forces were neutralized effectively by the Bangladesh government under Sheikh Hasina Wajed, removing a contentious crease on the bilateral fabric. Communication and trade ties have bloomed, with Dhaka emerging as New Delhi’s biggest partner in South Asia and India extending lines of credit for development. Shared cultural and linguistic ties between the two Bengals could also be used as a productive asset to deepen the alliance.

But there are irritants as well, largely from the Indian side. The sharing of river waters, primarily that of the Teesta, remains the principal bone of contention. Trade imbalances caused by non-tariff barriers on this side of the border as well as the tardy pace of the disbursement of India’s lines of credit must be looked into. Of equal concern are the warts on the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s Bangladesh policy. The rhetoric of the infiltrator — ‘termites’ in India’s home minister’s lexicon — has been used to derive political capital by the BJP in domestic politics. The domesticization of diplomacy was equally evident in Mr Modi’s unprecedented decision to visit a shrine revered by the Matua community in an attempt to derive political brownie points in poll-bound West Bengal. Mr Modi and his party must be careful not to fritter away the gains made by India and Bangladesh over decades at the altar of provincial politics. An injury to this deepening association could have broader — pan-Asian — consequences at a time when China is busy scooping up many of New Delhi’s allies in a widening embrace.