We are witnessing a discernible decline in the strength of democracy as a social and political system not only in India but also the world over. What is surprising is the fact that the erosion is not the effect of external shocks, like military coups or foreign aggressions, but rather through the damages wrought by elected governments. The cancer lies within. It is true that democratic systems are not perfectly defined, the observed systems vary from country to country, and they change in different ways over time. However, there is an ensemble of features that is common to most versions. None of the features taken in isolation defines democracy, but their collective presence provides the essential structure.

The most basic among these is the ability of citizens to exercise some sort of franchise by which they can choose their government and, more so, to change governments by voting politicians out of power. The second feature ensures that those elected to rule the country do not misuse the exercise of power. This is guaranteed through constitutionally-granted checks and balances that include political rights, civil liberties, and a set of neutral institutions that can restrict governmental arbitrariness, like courts of law, or other institutions like a free media, or, as in some countries, a neutral Election Commission. Above all, the ability to voice opinions that are critical of the government is central to the set of freedoms and rights that a citizen enjoys.

Each of these features is being compromised. Elections are hardly fair and free, with false propaganda, ballot-box tampering, and big-money campaigns making the individual’s vote worthless. Social media, along with the commercial electronic media, has made us tribal to the extent that we seek constant validation and comfort by being with people like us — people who think, behave and have lifestyles similar to ours. Hence, societies have become aggressively polarised. Social media gives one the courage of numbers and the safety of crowds. Each tribe wishes to have the other extinguished decisively and rapidly. The tribe in power is usually the groups from the far-Right of the political spectrum. A longish second half of the twentieth century had seen the rise of a liberal democratic polity, which also contributed to its own decay.

Now, in the twenty-first century, the far-Right is the more radical voice of change that gains support. The first act of governance, when these tribes enter the throne room of power, is to begin stifling the voices of dissent. Gradually, rights are curbed and civil liberties trodden over. All these can be done without altering the rulebook. It is the de facto world that changes sharply. Neutral institutions are purchased or threatened into servility. All these changes take place without much fanfare or explicit changes in laws and regulations. Existing rules are simply disregarded and flouted. Every feature that defines the broad contours of democracy gets distorted. The long arm of the State begins to crawl and extend to all and sundry — citizens, institutions, political Opposition, internal critics. This is necessary to ensure that any dissent or organised opposition beyond the ballot box is made dangerous and well-nigh impossible.

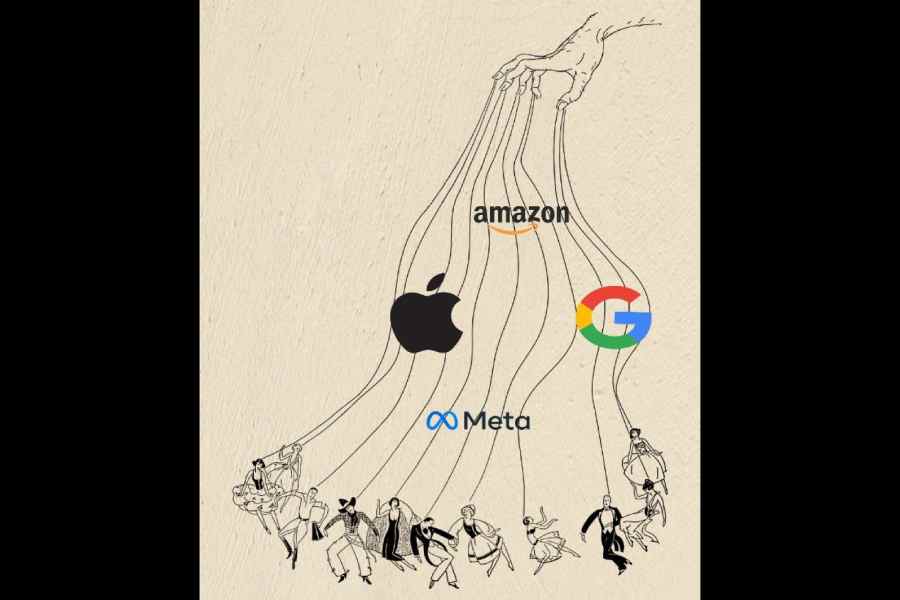

In the world of fake news and falsities, the charisma that authoritarian rulers enjoy is actually ephemeral. Big business rules the world of illiberal democracies, not the authoritarian leaders who hog the headlines. The de facto transitions in the features of democracy are linked to the vast changes that are happening in the structure of capitalism. The world of manufacturing and factory technologies is far less important now compared to the world of ideas, knowledge, and algorithms — the nebulous clouds of cyberspace. This is the world of high technology beyond the information and communications revolution. The explosion in data has given these large companies unprecedented power to control, manipulate, and influence human behaviour as never before. The power of governments, compared to what the big tech firms possess, is trivial. We are, in many ways, owned by the Mark Zuckerbergs and Jeff Bezoses of the world.

Industrial capitalism is giving way to a new type of feudalism. The Industrial Revolution emerged from the world of European feudalism where land was the primary asset and rent extracted from it was the principal source of income. This gave way to machines and manufactured capital as the main assets from which income flowed. Profits became the main source of income and the working class remained stable and with a reasonably secure wage. The new world emerging has data and information as capital and the income earned is a rent and not profit as normally understood. Some scholars have begun to refer to this as cloud rent in the age of the internet. When we post on Facebook, we are not working for Zuckerberg and he pays us no wages, but our post enhances his capital — data. This is not the wage labour to capital nexus of capitalism. Firms like Google, Meta, Apple or Amazon do not have workers in the sense that twentieth-century firms had. In those days, large firms used to have payroll figures that were 80%-85% of their top-line earnings. The big techs of today spend something like 1%-2% as wages.

This trend has a number of implications. The unprecedented concentration of wealth and income is not distributed through taxes and subsidies. The wealth is not used in widening the capital base or the sources of livelihoods. The old-style labour force with unions and collectives has given way to informal work and the unorganised gig economy. The tech giants of the world have way more power than any government in their ability to control mass behaviour. Indeed, despite the far-Right’s usual ideological arsenal of nationalist identity, the final validator of one’s identity remains the tech companies in cyberspace. Without Google or Apple confirming our identities, we are half a human being. If there is any long-drawn struggle in the transition to this new form of economic feudalism, it will be between the big tech companies and governments.

These captains of industry, to retain their control over wealth, need to create social polarisation and as well as the ability to reproduce the schism over time. The political pawns of these companies appear as the illusory political masters of the new order. They are mere actors strutting on stage, their dance choreographed from behind the scenes. It is a kind of feudalism because the source of earnings is a form of economic rent and the formal features of freedom associated with capitalism are no longer relevant. There is a tiny elite — the super-rich — who control governments, control our beliefs, influence our behaviour, and supply us with a stream of illusions. Religion and politics merge. Control is the key, and dissent has dangerous consequences. As far as the proverbial democracy’s man-on-the-street is concerned, there is a variety of goods — real and virtual — to choose from. He is socially disconnected, rather awkward in the real world, completely helpless without smart devices, and awestruck by the spectacular show of intelligent machines. All of us are on a high-tech ride to a distant past.

Anup Sinha is former Professor of Economics, IIM Calcutta