One of the earliest books of which I still have a vivid memory is a collection of fairy tales with brilliantly coloured illustrations. I was too young to be able to actually read the book, with its thick, large pages and a cover painting of an ant sailing in a walnut shell (using a straw to steer the vessel), but I knew that although the words on the pages were in the familiar Bangla script, the book was definitely something strange, and somehow ‘foreign’. It was not until much later that I realised that what had gripped my childhood imagination was a book of translations of Russian fairy tales. Since that time, more than half-a-century ago, I have read hundreds of translated works, ranging from poetry (Virgil, Kalidasa, Dante, Neruda, Lorca, Cavafy), to drama (Sophocles, Kalidasa again, Ibsen, Strindberg, Brecht, Ionesco, Karnad, Elkunchwar), to short stories (Borges, Kawabata, Maupassant), to novels (Cervantes, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Proust, García Márquez, Cortázar, O.V. Vijayan), to non-fictional prose (Plato, Aristotle, Montaigne, Descartes, Kant, Marx, Piketty) — given enough time, I could go on listing such names until they took up this entire column. For the most part, I have never judged these texts in terms of their fidelity to their originals, for the simple reason that I cannot read the languages in which these works were composed. So they have come to occupy a somewhat strange place in my inscape of good or important or influential books — as though they were all composed in the same two languages, English and Bangla, in which I have read them. To consider just one genre, it is as though all the novelists whom I love, ranging from Cervantes to Defoe to Austen to Dostoevsky to Dickens to George Eliot to Bankimchandra to Rabindranath to Calvino to Amitav Ghosh to K.R. Meera, have all written their works in some strange polyglot mixture of Bangla and English, and when I remember bits and pieces from their works, I invariably remember them in a muddled-up language that is peculiarly my own.

All of which is by way of trying to say that irrespective of the language in which a work was originally composed, or the language in which we encounter it, such works seem to reside in the same part of our imaginative mindscape. The problem arises, of course, when we consume the same work in two different languages, as those who have read Rabindranath in both Bangla and English, or Manto in Urdu and English, can testify; and this gets more complicated if we try to judge the relative merits and demerits of the same text encountered in two linguistic avatars, as it were. Things start to get even more confusing when the author herself, or himself, is the translator (Beckett, Tagore, O.V. Vijayan), and matters get positively maddening when more than one translation exists of the same work in the same language, with one made, or sanctioned, by the author, and the others by different hands. A case in point are the four English translations of Rabindranath’s Ghare Baire, all called The Home and the World, the first one translated by Surendranath Tagore, authorised by Rabindranath himself and published in his lifetime, the other three rendered into English by Sreejata Guha, Nivedita Sen, and Arunava Sinha, all published in the 21st century.

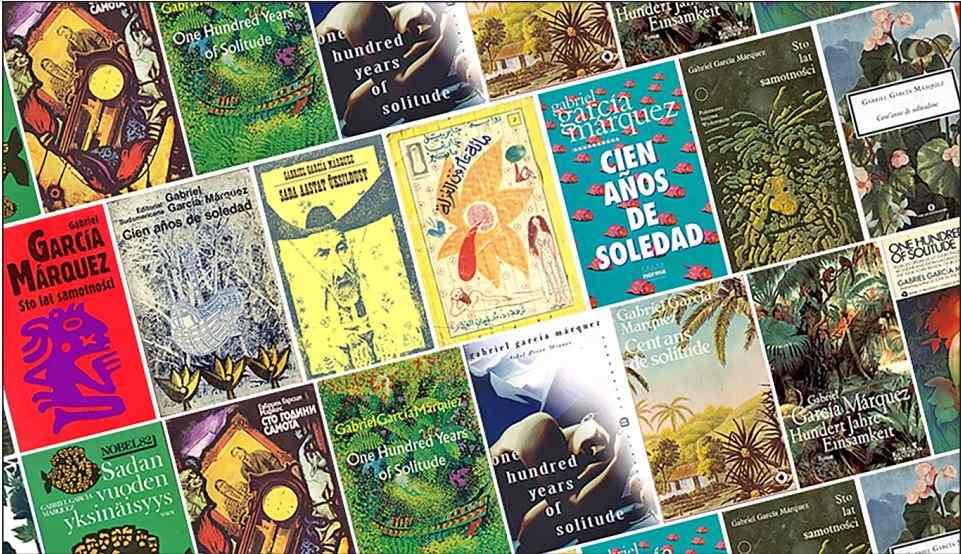

How, then, can we judge such translated texts? One way could be to ignore the source language text altogether and consider the translated text as though it was a work in the target language. One Hundred Years of Solitude has probably exercised a greater influence on the development of ‘magic realism’ in languages other than Spanish than it has in its language of original composition, with Gabriel García Márquez’s comment, that Gregory Rabassa’s English rendering was better than his Spanish original, making things even more confusingly exciting. For all intents and purposes, therefore, One Hundred Years is an English novel, of a strange and wondrous kind, one that had never really been encountered by its English language readers earlier.

All of which is by way of preamble to the basic point I am trying to make in this piece — that books, whether of fiction, or poetry, or drama or whatever, are still perhaps the most effective means of taking us out of ourselves, into the lives and times and minds of those who are (most) unlike us — and translated texts play an absolutely vital role in this process. Such translated works may not always be of the kind enumerated above, originally written in one language which has then been transmuted into another. I think of some works as ‘translations’ because the people, places, and things that populate them are not usually rendered in the language in which we get to read the work. The recent, brilliant, works of Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar — which give us an intimate, insider look into the lives (and much more) of Santhals — are one contemporary example of this.

As significant parts of the world, including the one we inhabit, take a homogenising turn, with leaders asserting a single identity — whether based on ethnicity, religion, or some other cultural marker — it seems to me that literature is one of the few remaining places that enables us to celebrate our varied, multitudinous selves. This is perhaps especially true of a country like ours, where we take the multiplicity of our identities for granted, or maybe it would be more accurate to say that this multiplicity is such a natural part of our daily existence that we probably don’t pause to reflect on it (as perhaps we ought to). One of the markers of this multiplicity, or, if one prefers, diversity, are the several languages in which we operate in our day-to-day transactions with others. It is this linguistic diversity that facilitates the proliferation of translations — of all kinds — for to be Indian is to be both translator and translated by others. Like most readers of this piece, I have grown up within (both ‘with’ and ‘in’) several languages, which underwent a whole complicated series of changes through the use, misuse, abuse, hybridisation and mongrelisation we (family, friends, neighbours) subjected them to on a daily basis. Even now, I am most comfortable in a ‘language’ that is a complicated khichuri of Bangla, English and Hindi; like most of my friends and acquaintances, I continue to use the diverse resources of these three primary language systems and to add the occasional flourish from several others.

When was the last time you heard shuddho (pure) Bangla unmixed with a word or phrase from another language? Whether in advertising jingles (“Surobhito antiseptic cream Boroline”), or in books (“Fight, Koni! Fight!”), or in the give-and take of crowded daily living (“aaste ladies!”), hybridity always seems to trump purity. Of course, some languages may be considered more equal than others when it comes to their acceptance into the universe of Bangla discourse, and others looked down upon, but that discussion can wait until another time. For now, as the powers that be seem hellbent on pushing a singular ‘Indian’ identity on us all, perhaps we ought to spare a moment to celebrate the delightfully mixed-up multifariousness that makes us what we are.

Samantak Das is professor of Comparative Literature and pro-vice-chancellor, Jadavpur University. Views expressed are personal