The Preamble to the Constitution of India, as it now stands, defines India as “a sovereign socialist secular democratic republic”, committed “to secure to all its citizens” justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity — in that order — with each one of these four terms further specifying the realm in which its virtues must operate in the nation that “the people of India” are giving to themselves. So, justice is to be enshrined in the realm of the “social, economic and political”; liberty ensured in “thought, expression, belief, faith and worship”; equality assured when it comes to “status” and “opportunity”; thereby creating a fraternity that will promote “the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity” of India.

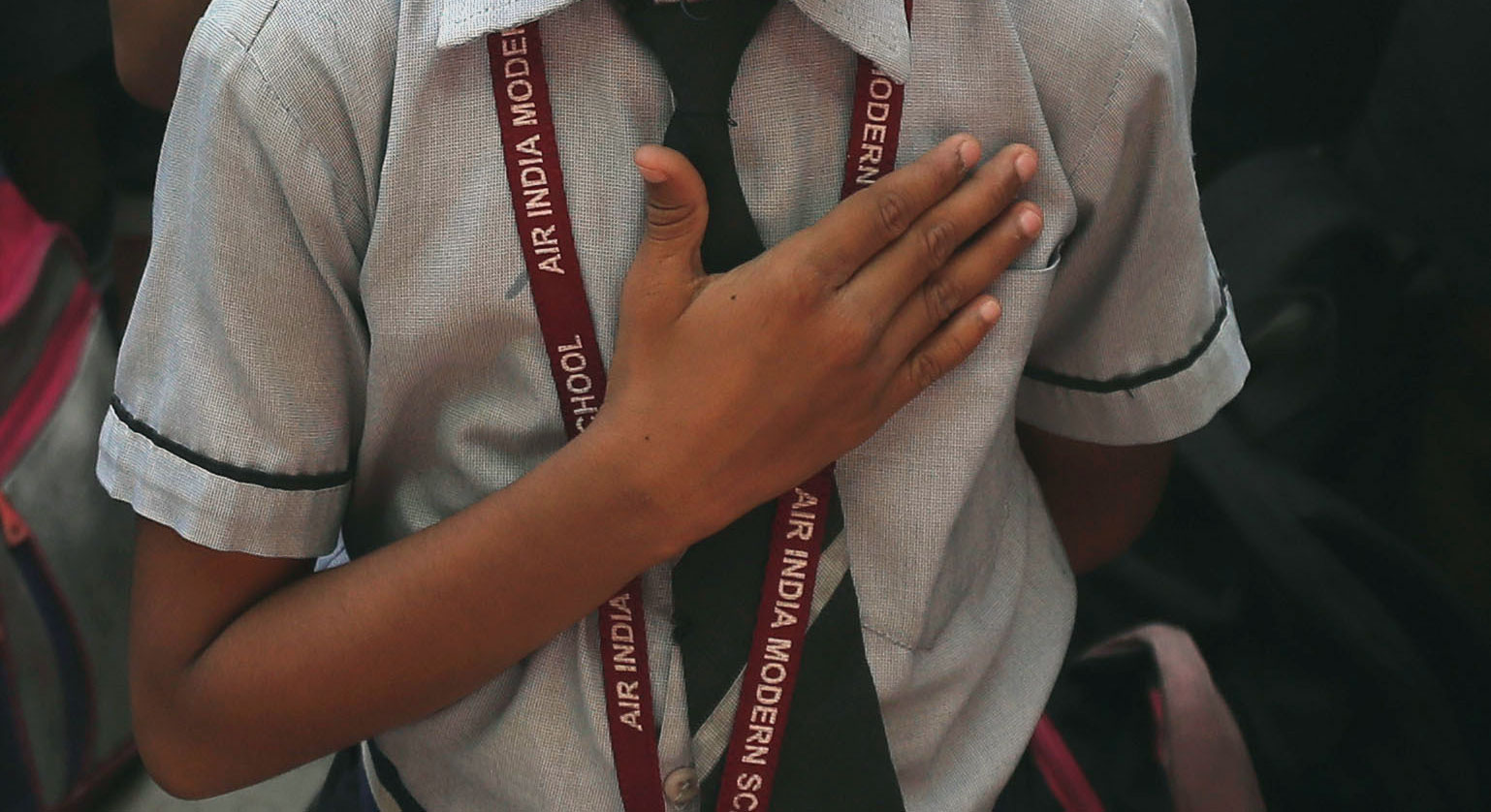

These are powerful words, long recognized for their ability to inspire and to move, and now being used across the country to challenge what is widely perceived as the communal underpinnings of the recently-enacted Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, especially when considered together with the proposed National Register of Citizens and the National Population Register. Young women and men in college and university campuses, people from all walks of life, gathering in open spaces, parks, and gardens across the country, usually led by women — some of whom are taking part in public demonstrations for the first time in their lives — have weaponized the Preamble to openly challenge the CAA, NRC, and NPR, and, by extension, the government that has declared its intention to enforce them. As commentator after commentator have remarked, and as many (including this writer) have experienced first hand, the most noticeable thing about these demonstrations is that there seems to be no central command leading them, nor does there seem to be any significant role being played by political parties or religious leaders in shaping or guiding such protests. The second thing that is obvious is that these aren’t emphatically “Muslim protests”, even though they are directed at the anti-Muslim bias of the CAA, and the fear of Muslim victimization should the NRC and the NPR be enforced.

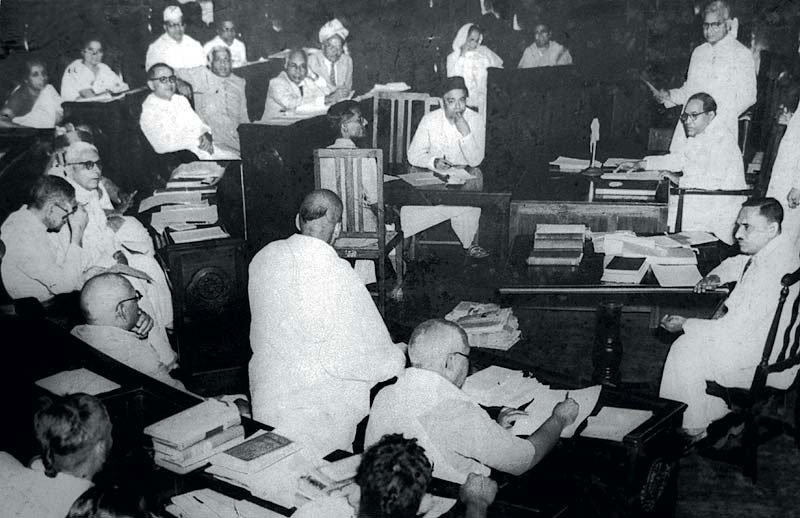

Our Constitution is a living document, as witnessed by the many changes it has undergone since its formal finalization on November 26, 1949; with some amendments universally lauded and others contested bitterly and, on occasion, repealed or modified (for example, perhaps the most contentious of them all, the forty-second amendment of 1976, introduced during the Emergency), but a consideration of such changes is well beyond the scope of a brief discussion such as this. However, the vibrant and fundamentally democratic nature of the Constitution is perhaps nowhere better demonstrated than in the 12 volumes recording the discussions and debates of the Constituent Assembly, right from December 9, 1946, when its members met for the first time, to the signing of the Hindi and English copies of the final Constitution by members of the Assembly on January 24, 1950. These 12 volumes are freely available here, and they make for truly fascinating reading. Problems and issues that remain contentious to this day were discussed, debated, voted on, and resolved, in a manner that can only be characterized as civilized, respectful towards differing views and opinions, and leavened throughout with an almost impish sense of humour. I am not suggesting that an interested individual should read all 12 volumes in one go, but for nearly every issue that is sought to be used to divide and confound us by our political leaders, the proceedings of the Constituent Assembly provide much food for cogitation. One such issue being the place given, or, to be more accurate, not given, to divinity and the then recently-deceased Father of the Nation in the text of the Constitution.

When the Constituent Assembly met on October 17, 1949, with the text nearing finalization, the issue of the Preamble, and its exact wording, was taken up. Several amendments were moved, for which notice had been given by members, “in which”, as Rajendra Prasad, the president of the Assembly, put it, “the name of God is brought in, or the name of Mahatma Gandhi is brought in, or both together”. The first of these (amendment No. 430) was moved by H.V. Kamath, who proposed that the phrase, “In the name of God”, should precede “We, the people of India” as the opening line of the Preamble. After the amendment had been negated, Shibban Lal Saxena moved that the Preamble begin with the words, “In the name of God the Almighty, under whose inspiration and guidance, the Father of our Nation, Mahatma Gandhi, led the Nation from slavery into Freedom, by unique adherence to the eternal principles of Satya and Ahimsa, and who sustained the millions of our countrymen and the martyrs of the Nation in their heroic and unremitting struggle to regain the Complete Independence of our Motherland” and then go on to “We, the people”. Saxena’s argument for introducing both divinity and the Father of the Nation into the Preamble was predicated on the fact that such a “great piece of work” (his words) as the Constitution, of which everyone ought to be proud, should acknowledge the contribution of Gandhiji and also recognize the “realm of the spirit” that was an integral part of the new nation. It was J.B. Kripalani whose intervention was crucial at this point. “We must be very sparing of the use of the name of the Father of the Nation. My friend Shibban Lal knows that I yield to nobody in my love and respect for Gandhiji. I think it will be consistent with that respect if we do not bring him into this Constitution that may be changed and reshaped at any time.” This insistence on the Constitution as a living, changeable entity, subject to the will of “We, the people”, as opposed to the eternal virtues of both God and Gandhi, led Saxena to withdraw his proposed amendment with grace. When requested to speak, as he had done at the commencement of the proceedings of the Constituent Assembly, Kripalani began by commending Rajendra Prasad for saving the discussion on the Preamble towards the end of the Assembly’s deliberations: “Sir, you like a good host, have reserved the choicest wine for the last.” He then went on to say that “what we have stated in this Preamble are not legal and political principles only. They are also great moral and spiritual principles... ” His injunctions that “on this solemn occasion, it is necessary to lay down clearly and distinctly, that sovereignty resides in and flows from the people” and that “we [the members of the Constituent Assembly] are the servants of the people” still resonate in our difficult and fractious times.

Whether CAA 2019 is violative of constitutional principles is a matter for the courts to decide, but — given, especially, the anti-intellectual, anti-democratic, majoritarianism that our rulers seem to take pride in celebrating — it is well worth our while to go back to the foundational text of our republic, and to the process of its formation, if for no other reason than to equip ourselves for the long struggle that seems to loom ominously ahead of all of us.

The author is professor of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, and has been working as a volunteer for a rural development NGO for the last 30 years