Public functions often attract their fair share of attention. Republic Day is not an exception. This year, eyebrows were raised by the depiction of religious symbols in the tableaus rolled out by some states. January 26, after all, was the day when India embraced a Constitution that sought to uphold the principle of secularism. There has also been talk about some of the choices made by the Centre when it comes to the recipients of civilian awards. This year, an activist associated with an organization that reportedly enjoys the patronage of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh was conferred with the Padma Shri, the nation’s fourth-highest civilian award, in spite of her association with the endeavour of religious conversion.

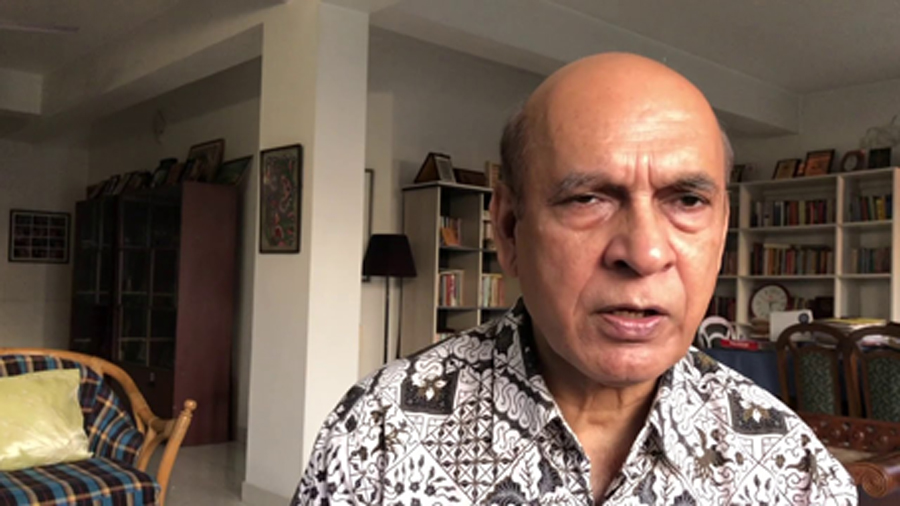

But this is not to say that the Centre got everything wrong when it came to bestowing national honour. There can be no disputing its decision to award Quazi Sajjad Ali Zahir with the Padma Shri. Mr Zahir, one of the two luminaries from Bangladesh who were honoured by India, is not only a veteran of the Liberation War of 1971 but has also spent much of his life educating citizens about the importance to remember and learn from periods of genocidal turbulence. New Delhi’s gesture must be applauded on two counts. First, this is a pragmatic decision in political terms, signaling to Dhaka and the world India’s resolve to deepen — and smoothen the creases in — the ties with its neighbour in the east. Second, there is also a certain degree of poignancy about the selection. Mr Zahir’s recognition, quite pertinently, coincides with the week in which Auschwitz — an enduring symbol of the horror of genocide perpetrated by Nazi Germany during the Second World War — was liberated. Mr Zahir’s life and work and India’s recognition of both are a testament to the need to educate citizens and mobilize collective resistance against oppression of every conceivable kind around the world. This is because genocides, much like a virus, have a propensity to return.