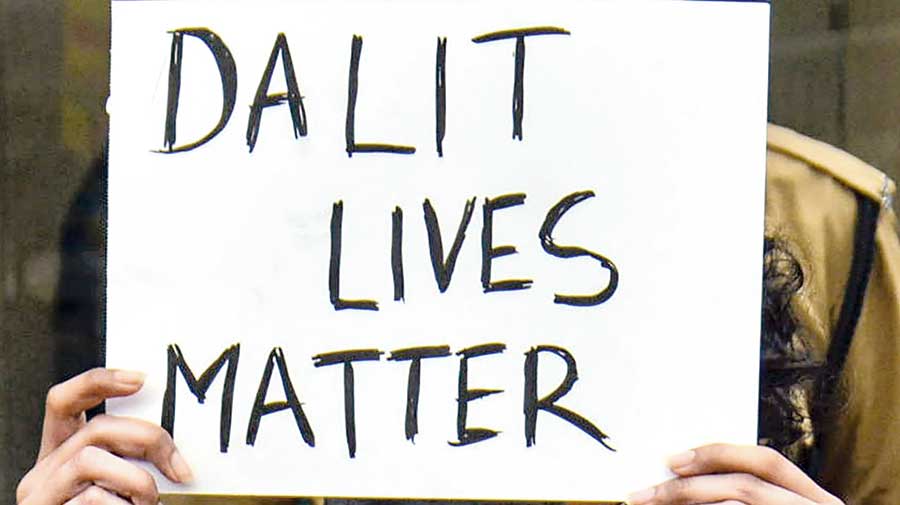

A steady rise in cases of atrocity against Dalits reflects the deep-seated caste bias in India. Public servants are not immune to this prejudice. The manner in which local authorities approached the gang rape and mutilation of a Dalit woman in Hathras is a testament to the bias. The officials delayed registration of the crime, attempted to pressurize the victim’s family, participated in the destruction of evidence, and prevented the media from covering the case. By not taking appropriate action against these officials, the State is deviating from constitutional and international guarantees of protection, dignity and substantive equality.

The Constitution recognizes ‘caste’ as a marker of discrimination against citizens. Article 15(4) and Article 16 enable the State to undertake affirmative action for marginalized communities, including Dalits. Parliament has implemented policies such as reservations for Dalits in public educational institutes and government jobs to uplift them socially and economically. The Constitution, thus, strives for ‘substantive equality’ — a multidimensional view of equality — in a bid to redress historically created systemic disadvantages, combat prejudice and stigma, prevent political exclusion and accommodate structural changes.

The Supreme Court recognized the constitutional vision of substantive equality in State of Kerala vs N.M. Thomas. It acknowledged that people were not created equally, and that the claim for equality was a protest against unjust and unjustified inequalities. Thus, the State had the power to enact affirmative action to ensure a level playing field for India’s various caste groups.

The Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 is another manifestation of the goal of substantive equality. It provides special protection to SC and ST members from humiliation and harassment. It criminalizes acts of public servants who neglect their duty to protect SCs and STs. Those charged under this statute do not have recourse to anticipatory bail. In State of MP vs Ram Krishna Balothia, the bar on anticipatory bail was recognized as an important protection for SCs and STs by the apex court; otherwise, the accused would misuse their liberty to terrorize their victims and prevent an investigation. Cognisant of this fact, Parliament had overturned a decision by the Supreme Court to grant additional protection to public servants in cases under the Act. This parliamentary intervention is an acknowledgment that Dalits continue to endure horrors. The Hathras officials who burnt the body of the victim and refused to file the complaint had not been charged under the Act.

India has ratified several human rights treaties that impose international obligations. In its latest cycle of the UNHRC Universal Periodic Review, the Indian delegation had “noted” nine caste issue-based suggestions. However, Dalit rights activists say that there has been no further information on how the government seeks to implement these suggestions to end caste-based violence.

Human rights, in parlance of international law, are achieved through obligations of conduct and of result. Where the former would require “action... calculated to realize the enjoyment of a particular right... [t]he obligation of result requires States to achieve specific targets to satisfy a... substantive standard.” Honouring substantive equality would remain a hollow promise unless it is implemented to satisfy the standards of social, economic and political equity.

For a State to eradicate the core of discrimination, it must counter it through the language of human rights entrenched in constitutional and international law. It must give life to this language through actions of its machinery to implement these laws faithfully.