While petitioning the court, beseeching judicial intervention to prevent the killing of wild animals in the districts of Bankura, Purulia, and East and West Midnapore during the traditional hunting festival of tribal people — the Disum Sendra or the Shikar Utsab — the secretary of the Human and Environment Alliance League made a rather interesting observation. “There is nothing tribal about these festivals,” he is reported to have said. “Clad in denims and T-shirts, the intoxicated men are out for a day of pure recreational hunting.”

One inference that can be drawn from the statement is the suggestion of the hunters masquerading as adivasis. Their sartorial choice — denims and T-shirts — the argument goes, gives them away. Here, tribal identity is being deciphered on the basis of the understanding of what constitutes and differentiates the modern from the primitive. Indigenous people — the primitive ones — cannot wear clothes that are the insignia of the civilized.

Unfortunately, the line separating the savage and the civilized can be rather fluid. The resultant confusion — is the savage civilized and the civilized a savage? — has exercised many a luminous mind, one of whom was Verrier Elwin, the anthropologist, ethnologist and activist, who was, in many ways, more Indian than English. Ramachandra Guha’s excellent biography, Savaging the Civilized, shows which side Elwin was on of this vexing question. Elwin chose specific tribal institutions and customs to posit the primitive as the modern. One such institution was the ghotul, the Muria dormitory, the “arena of encounter and friendship, of play, music and dance”, that Elwin discussed in detail in The Muria and their Ghotul to not only challenge its vilification by a puritan, religious, urban sensibility but also to underline the superior moral plinth of adivasi society. He pointed out that incidents of venereal disease, prostitution, rape and child marriage, the gifts of civilization to mankind, were absent among the Muria. Strikingly — and cannily — Elwin sought to link the Muria ideas of pleasure and sexual autonomy with the Hindu civilizational ethos, further diffusing the lines between the cultured and the crude: “... that freedom and happiness are more to be treasured than any material gain, that friendliness and sympathy, hospitality and unity are of the first importance, and above all that human love — and its physical expression — is beautiful, clean and precious, is typically Indian. The ghotul is no Austro-asiatic alien... Here is the atmosphere of the best old India...” Even while examining transgressions like crime in Maria society (Maria Murder and Suicide) — the law in Elwin’s India was predisposed to condemning entire communities as criminal — Elwin argued that murder among the Maria was the consequence of an “astonishing innocence”, an innocence Elwin contrasted with some of the perversities of civilization: “They [the Maria] are... ignorant of caste and race prejudice... They do not form themselves into armies and destroy one another by foul chemical means. They do not tell pompous lies over the radio...”

The public discourse on the shifting boundaries between the savage and the civilized has been invigorated by a number of Indian scholars and artists. Satyajit Ray was among the latter. Ray first examined this complex equation in Aranyer Din Ratri. The film was released six years after Elwin’s demise, but it was quintessentially Elwinian in spirit. Thus, Palamau’s adivasis, enfeebled by poverty and disease, still retain the resilience as well as the moral force to expose the turpitude of modernity, the wickedness manifest in the choices made by four friends, city dwellers all, who visit a forested idyll. Ashim’s bribing of the caretaker and DFO to gain unauthorized access to a bungalow or Hari’s seduction of Duli, the tribal woman, is, in a way, a condensed register of the pillaging of the savage by the civilized.

Ray’s last film, made 21 years after Aranyer Din Ratri, felled the myth of modernity’s benevolence even more decisively, reaffirming, in the public eye, the maestro’s solidarity with Elwin. The hollow heart of modernity and the consequent erosion of values are exposed, again and again, with the protagonist (Utpal Dutt) — the agantuk — clinically dismantling civilization’s false claims of supremacy — material, moral, aesthetic, ethical and intellectual — over the savage in a telling conversation with his inquisitor (Dhritiman Chaterji).

But the scholarship that challenges Elwin’s — and by default Ray’s — position of ecological romanticism is compelling too. Archana Prasad’s Against Ecological Romanticism, to cite one example, counters Elwin’s understanding of the Baiga as a self-sustaining community independent of the political economy and the market by citing evidence of the Baiga’s integration with the colonial and capitalist systems. Another criticism has an equally contemporary relevance. Elwin’s reassessment of the relationship between the tribal people and the Hindu faith — he had called for the mobilization of Hindu organizations as a bulwark against missionary interventions around the time of Independence — proved to be a catalyst for the proponents of Hindu revivalism who, unknown to Elwin, would eventually undermine the sovereign tribal life. That ecological romanticism has complemented religious fundamentalism is a proposition, which demands rigorous debate and research.

Hindutva has been quick to exploit the loophole in Elwin’s reasoning to camouflage its aggression — ideological and political — towards aboriginal society as assimilation. Prasad notes that as far back as 2002, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its allies had been brazen enough to conclude that the Hindu caste hierarchy has been especially sensitive when it comes to civilizing the savage, adjusting “to the needs of the hunters-gatherers”.

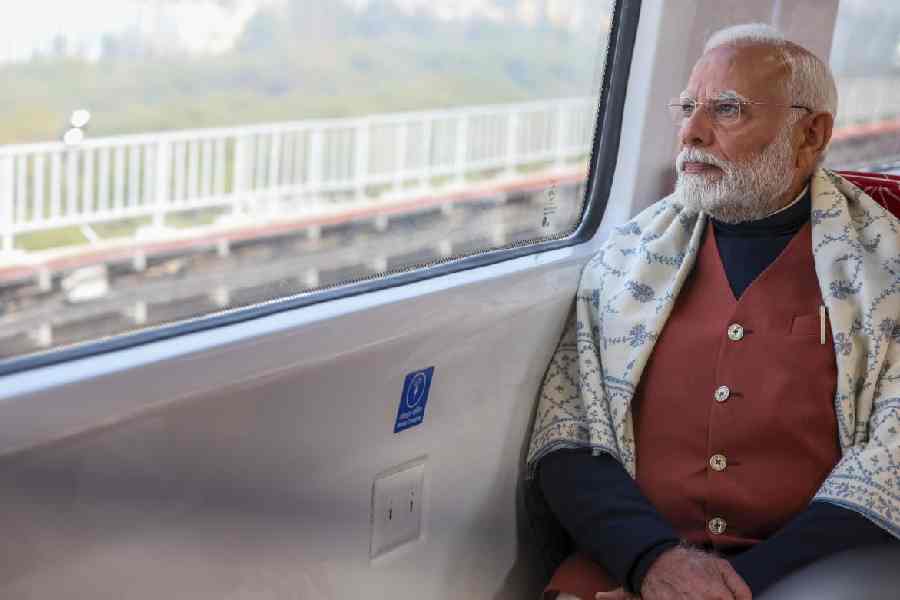

This barely-concealed condescension, common to colonialism and the Hindutva project, resurfaced recently in an interview that Narendra Modi — exit polls have predicted that he will return to power — gave to a newspaper. Responding to the charge that certain segments of the population no longer felt integral to Modi’s model of nation-building, the prime minister said, “As for Dalits/tribals, I have been of the opinion that why shouldn’t Dalits/tribals/Muslims be chairmen of, say, Lions Club. Why should everything be in politics?”

This philosophy of empowering the marginalized is singular. It imagines them as leaders of a benign philanthropic organization while suggesting — legitimizing? — their redundancy to the political project.

Can the savagery of the civilized — envisioned, chronicled and criticized by Elwin and Ray — acquire a more sinister edge?