I am writing this piece on a day when many in my country are hailing the return of Rama to Ayodhya. In making such a claim, falsities are being dubbed as historical. The idea of Rama returning implies that he was removed or banished, much like he was in the epic. This also means that there is a villain; in this case, it is Babur. But this is extended to include Muslims in general. This resonance has been cleverly used to tap into the sentimentality of Rama coming back to his rightful place of birth. Contrary to this story, the Supreme Court verdict that allowed the construction of the Ram temple in Ayodhya stated that there is no proof that a temple had been demolished to build the Babri masjid since there was an intervening gap of about four hundred years between the dating of the underlying structure and when the mosque was built. But when people in positions of power cutting across political, social, religious and spiritual lines repeat falsities ad nauseum, they become the truth. There are others who conveniently accept those parts of the Supreme Court verdict that suit the story they find palatable.

In society, we seem to have two broadly acceptable models of how bhakti is expressed. The privileged and upwardly mobile classes and castes have formulated modes of socio-ritualistic behaviour that they believe are formal and sophisticated. This calls for muted facial movement, specific styles of gesticulation, a certain degree of studied seriousness, and careful participation in activities such as chanting. In an antithesis of this manifestation exists the vocal, vigorous, physical, carefree and possessed expression of bhakti usually found among the underprivileged classes, castes and genders. There is tension between these expressions, with the former positioning itself as ritualistically superior and philosophical. There are, of course, shades in between but they are very difficult to identify. Over a period of time, they fall into one of these two categories. I will set aside the discussion on whether this kind of standardisation is even acceptable because that is an entirely different debate. The fact that they exist and are truthfully experienced cannot be denied.

When these bhakti experiences are genuine, they are palpable even to the observer. In those moments of prayer in our homes, when the screen in front of the deity is opened in the sanctum sanctorum, or when we stand below the deity as he/she is in procession around the temple, there is an exhilarating quietness that envelopes us, much like the moment when we watch the sun rise or listen to an exquisite piece of music. Those moments are deeply vulnerable and revealing. Revealing because as you give yourself up to the lord, you also see yourself for what you are, without any social trappings or obsessions. You surrender without any precondition. I am sure this also happens to those who are deeply involved in ritualistic prayer.

Another form of giving oneself to god is seen in the words of bhakti poets, such as Andal and Tukaram: this is the unadulterated and limitless explosion of love. The physical expressions of bhakti are visible when people put themselves through pain, walking on fire or piercing their cheeks with symbols of the deity. I was at the Nallur Kandaswamy (Muruga) temple in Jaffna a few months ago and witnessed hundreds of devotees call out for Muruga loudly in yearning. It was moving and powerful because there was a communion in that moment. A unison that came from the commonality of what they were seeking — Muruga. There were no external triggers and no planted agenda. For this to happen, the foundation of our relationship with the god cannot be based on triumphalism or retribution. I am certain that those who felt Muruga at that moment are not untainted human beings. But when they came to the temple and gave themselves up to Muruga, there was a momentary transformation.

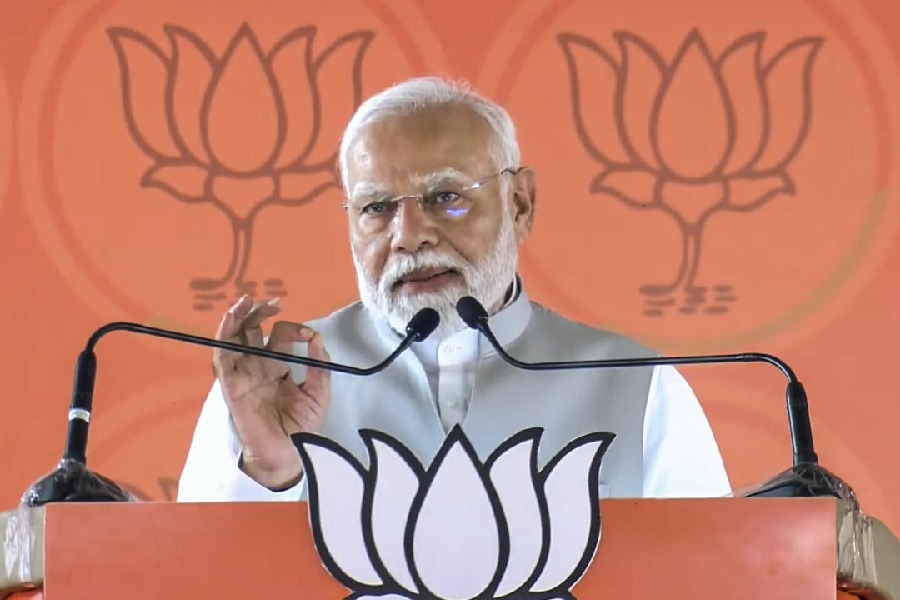

Over the past few weeks, bhakti has been evoked in its spoken, written, pictorial, symbolic and photographic forms. The images of the prime minister in perfectly curated meditative postures and those of him performing rituals have enamoured the devotees of Narendra Modi. Modi ensures that he conforms to the social behaviour, body language, facial expressions, use of certain words and tonality of the voice that work for elite bhakti-ites. Let us keep in mind that this is an aspirational style of bhakti. So the rest of society also sees this as befitting of a leader. Local members of his party and ‘fringe’ elements make sure to give bhakti’s other — overt — presentation a dangerous twist. They demonstrate their bhakti with frenzy, screaming ‘Jai Shri Ram’, waving flags, planting these flags on other religious buildings and purposely going into Muslim localities and proclaiming Rama. All these are seen as over-enthusiastic expressions of the love for Rama, or are given a go-by as the venting of long-time angst. To even the most disinterested person, it should be obvious that Modi’s filmed moments are choreographed; yet the devout are not uncomfortable. There are a few possible explanations for this. They do not care whether Modi is being true or not as long as he emphasises a forceful Hindu position and ‘puts Muslims and Christians in their place’. Or since he does all that is required in the upper-class/caste book of religious behaviour, they trust him in toto. If not the above two, it can just be the fear that saying anything against the grain may land one in trouble.

The lack of any discernment between archetypical bhakti frames and these manipulated versions allows Modi and others to get away with provocative and intimidating statements against minority communities. At the same time, it gives unruly elements in their party the licence to go on a rampage unquestioned. There is a substantial overlap between those who have fallen for the assertive Hindu narrative and those who are celebrating the way Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party have gone about things in the past few weeks.

Among the elite, those who have engaged deeply with the philosophical side of Hinduism have disappointed me the most. I am unable to fathom how they are able to quietly watch Dalits and Muslims being attacked in the name of their religion, speak with such callousness about the destruction of the Babri masjid, not feel any discomfort with the fact that hundreds lost their lives in cycles of violence that emanated from the incidents of 1992 and justify the current opulent blitz. What Vedanta did they imbibe when they are unable to keep aside their baser, vengeful instinct, recognise the internal violence, and move towards humanity? How can they, in the case of the inauguration of the Ram temple, not call for moderation?

While many speak about the collapse of our democratic values, very few recognise the rampant deterioration and forgery in our bhakti fabric. Our propagation of the fake and the celebration of threatening conduct as aspects of faithfulness are deeply troubling. In one of his compositions, Tyagaraja said, “they walked all the way to Ayodhya yet were unable to find Rama.” He then goes on to say that Rama lies within our ‘self’. In his Adhyatma Ramayanam, Thunchathu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan wrote that when Rama asked Valmiki which was his real abode, Valmiki responded by saying that his abode is in the person who sees all creatures as one, with no malice towards anyone and worships him in peace. Bhakti lies in these realisations.

T.M. Krishna is a leading Indian musician and a prominent public intellectual