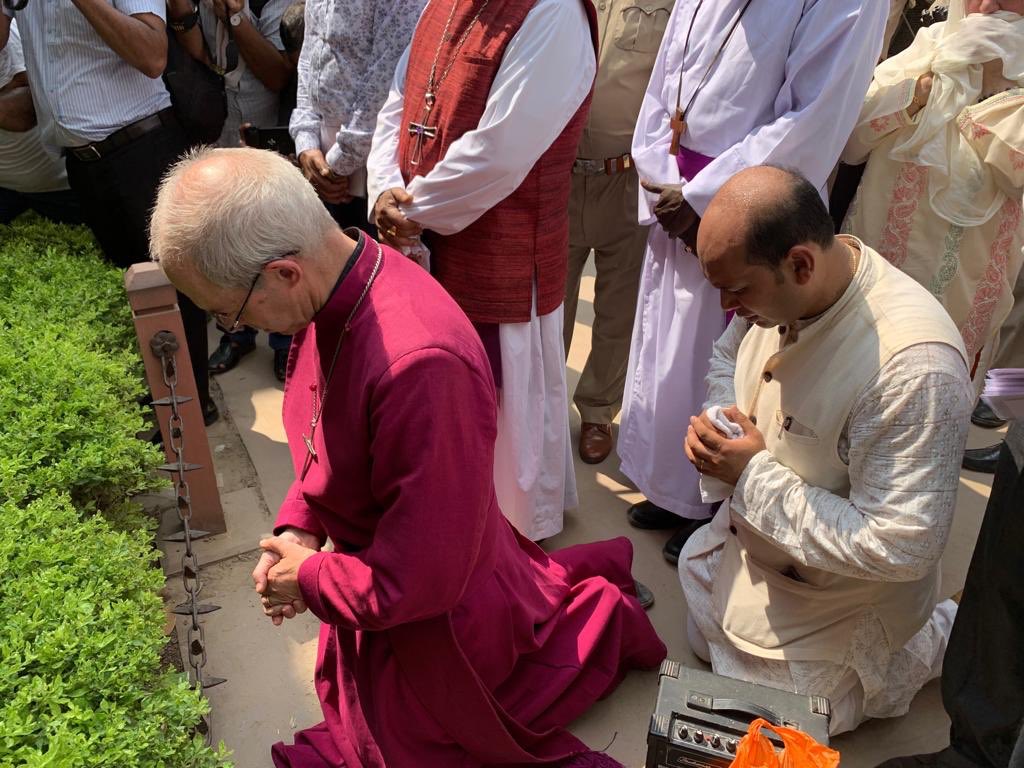

Sorry, indeed, is the hardest word. What adds to its weight, history and politics would confirm, are the contradictory pulls that inform the testy relationship between morality and diplomatic stratagem. The unqualified contrition expressed by the visiting dignitary, Justin Welby, the archbishop of Canterbury, for the butchery perpetrated by British troops on a crowd of Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims and Christians in Punjab’s Jallianwala Bagh 100 years ago is certainly welcome. What makes Mr Welby’s gesture particularly poignant is that his country is yet to issue a formal apology for an atrocity that had been instrumental in altering irrevocably the shape of India’s anti-colonial struggle. One former British prime minister had talked of ‘deep regret’; her predecessor had found the episode ‘deeply shameful’. What may have prevented these heads of state from uttering the words that have now been spoken so eloquently by Mr Welby is that charters of apology for crimes committed by imperial powers in former colonies have often strengthened demands of financial reparation among the people who had been wronged. Britain, for example, has not only apologized for its excesses in Kenya but also agreed to disburse a large sum as compensation among bona fide claimants in that country. In 2015, Japan agreed to apologize and compensate for the ill-treatment of South Korean women during Seoul’s occupation by Tokyo.

Yet, the discourse of recompense is yet to resolve some relevant — fundamental — philosophical questions. Should the sins of the father sully the hands of the son? What is the degree of complicity of, say, the modern, average Briton in the savageries executed by his colonial ancestors around the world? The history of colonialism was without a doubt a turbulent, immiserizing and violent experience for the people and nations that endured it. But can atonement, even when delivered from the highest quarters, truly compensate for the losses — moral, cultural and economic — suffered by the subjects of an imperium? A more effective way of making remorse meaningful would be to forge an equal partnership between the aggressor and the victim to heal the wounds of the past. This healing is predicated upon the creation of a knowledge that could be instrumental in preventing the recurrence of such transgressions. The knowledge, in turn, would come to fruition if both nations collaborate in terms of resources and expertise to explore and learn from a shared, but difficult, past.