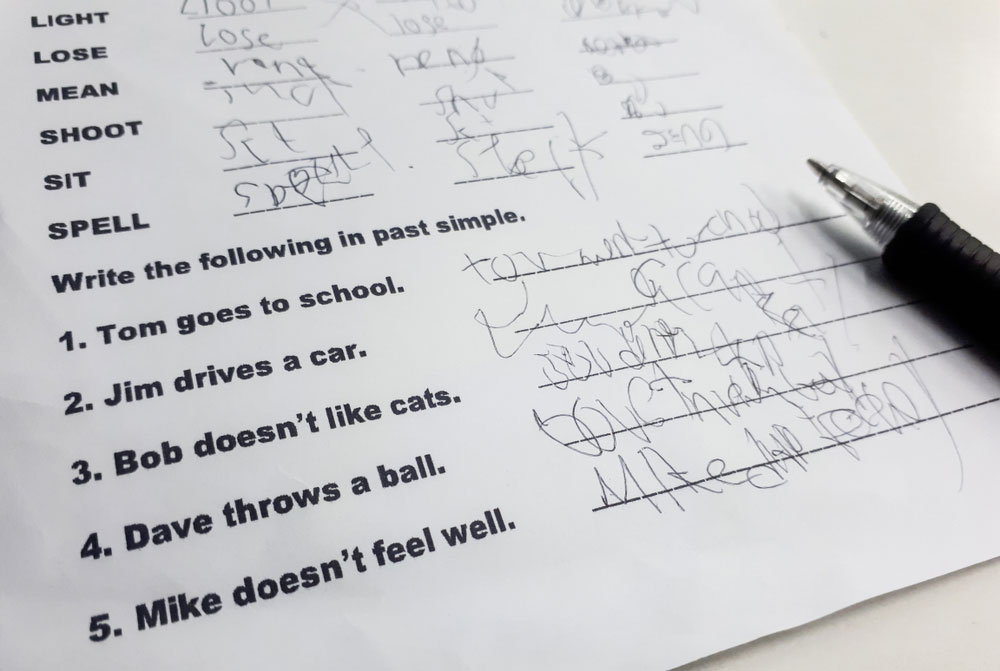

People take handwriting for granted. If they are not calligraphers, that is. Only schools are serious about it — or were till some years ago — with classes dedicated to handwriting practice that enveloped the perkiest child in gloom. Marks were deducted for ‘bad’ handwriting even in classwork on history or life science. ‘Good’ handwriting probably signalled education, culture, respectability, even artistic sensibility, as well as politeness — it was polite to be legible. But the labours of teachers often went in vain, for the ‘adult’ handwriting that developed as children grew up often had little to do with the rigours of the classroom. Some wrote big and some wrote small, some scratched in hurried strokes while others curled and looped in profusion; if one had the line of words rising in an elated slope, another’s would droop in profound dejection — in short, freed of the intimidating regimentation of school, handwriting blossomed in as many varieties as did personalities. Had that not been the case, how would the indispensable ‘handwriting expert’ of the classic detective story have been giving crucial evidence in imagined courtrooms?

But there would have been enough cause to flummox those handwriting experts during the current pandemic. A recent study — one of almost 200 people —has shown that people’s handwriting is changing. Experts have said that the comparison of pre-pandemic handwriting and the writing now shows an increased sensitivity, a feeling of lost direction and anxiety. It is the brain that writes, not the hand, say graphologists, so changed circumstances and changes of mood may lead to changes in writing. Opinion is still divided as to whether such insights into the psyche are possible by studying handwriting, although there is general agreement that illnesses, ranging from depression to dementia, do alter it. But it can be easily imagined that if distraction, anxiety, or just a rush to get a job done can produce a sloppy or scratchy script, trauma on the scale of the present pandemic might so affect the brain as to alter its more regular expressions too.

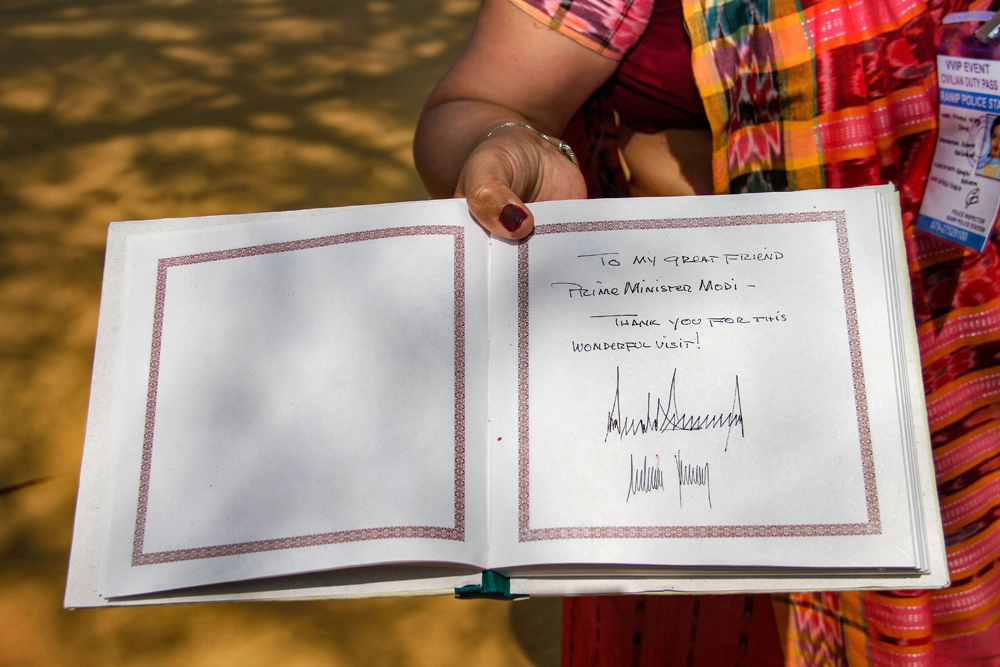

Clues to the subtler changes wrought by the atmosphere of fear, however, may not be very easily available through these means: it is little wonder that the sample pool is so small. Handwriting is gradually becoming a rapidly disappearing activity, not only in the more prosperous countries but also among those in India who can afford to be literate enough to produce long enough samples of handwriting before and during the pandemic to be assessed for mood. Regional languages still have some hope to be put down by pen on paper but the technology of the computer and the smartphone has swallowed much of that as well. The time may not be far off — somewhat beyond the novel coronavirus period though — when handwriting will be studied with as much curiosity as cuneiform writing and hieroglyphics. At least there are no more handwriting classes.