In the World Happiness Report released by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Indians stand grumpily at the 126th position out of 146 countries. India’s ruling party, expectedly, dismissed the report, while the Oppositionfound one more reason to criticise the government. The report on happiness thusled to unhappy political bickering.

Happiness, especially collective happiness, has been at the heart of many debates concerning morality, ethics, governance and politics. Philosophical treaties onthe purpose and the meaning of life considered happiness to be a worthy pursuit, although there have been differences on what actually constitutes happiness. Defining happiness is difficult because of its amorphousnature — it is simultaneously mental and material, personal as well as public. The quality-quantity dichotomy adds to the complications.

In his works on ethics, Aristotle talks of eudemonia. He explained eudemonia to be the highest goal of the human self that can be attained through the realisation of inherent virtues by means of rational functioning. This conception of happiness is applicable to both individual and society. Thus, public happiness is an outcome of collective reasoning — a defining feature of modern-day democracy.

Collective happiness has also shaped the contours of morality and justice. Utilitarians argued that any morally justified action should be evaluated on the basis of its ability to generate happiness. To the utilitarian moral calculus, what produces greater happiness for a greater number of people is justifiable action. The views of utilitarians were criticised for their initial failure to differentiate between happiness and pleasure. Nevertheless, they continue to influence many of our social and economic decisions regarding collective life, such as the ideas of the welfare State and the redistribution of resources that are aimed at maximising collective happiness. Collective happiness gradually paved the way for the present-day development discourse in which happiness is attained through development, freedom, rights and the expansion of human choices.

Happiness has also been measured in terms of wealth and income. Capitalism defines happiness in material terms. It propagated the idea that happiness is a journey of endless material acquisition and prioritised individual happiness over community well-being. In its pursuit of collective happiness, communism, on the other hand, ended up ‘forcing’ people to be happy. However, the quality of human life is assured neither by material possession nor by disciplinarian imposition since human beings value immaterial components that constitute happiness.

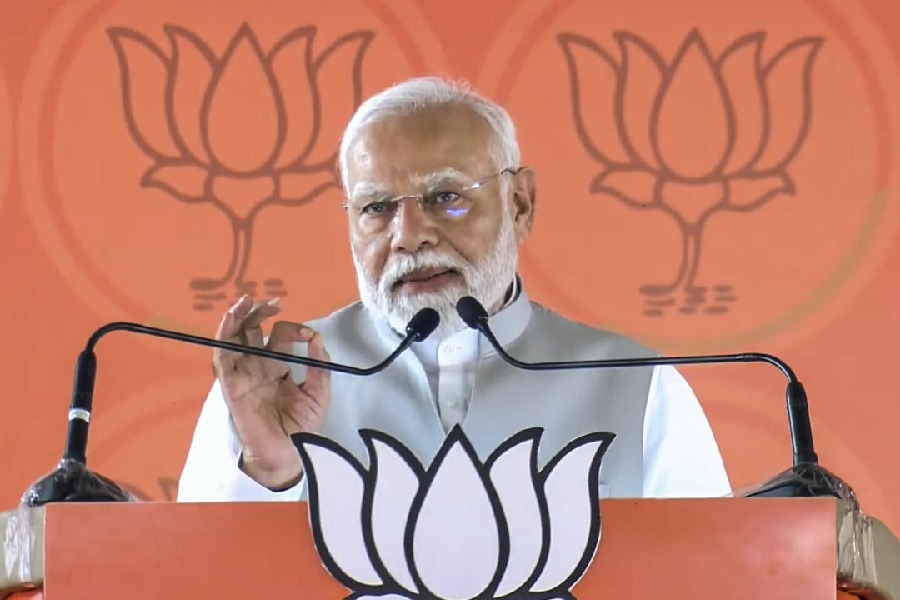

The political aspect of happiness has remained a constant. Be they kings (or queens) and their subjects or elected rulers and their citizens, they all want the people to be happy. Unhappiness is the subtlest form of indictment of a regime and an incipient threat to its stability. Therefore, every ruler dreads an unhappy population, especially in a democracy. However, the duty of ensuring the happiness of the people does not always bring out the best in rulers. When happiness is defined according to the convenience of rulers, particularly in a democracy, it completely upends the relationship between power and people. Rulers absolve themselves of accountabilities and citizens who make their unhappiness clear are seen with suspicion. The political narrative is framed in such a way that these people are discredited for the failure of those in power. Another part of this narrative is the envisioning of an enchanting utopia — one that is on the verge of being fulfilled. This utopia is often majoritarian in nature. Those who do not subscribe to this vision are accused of disloyalty, corruption and subversion.

What is often forgotten is that in a democracy, the duty of the State is not to produce happy citizens but to create an environment conducive for the citizens to find happiness by exercising reason and emotions.

Nirupam Hazra is Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work, Bankura University