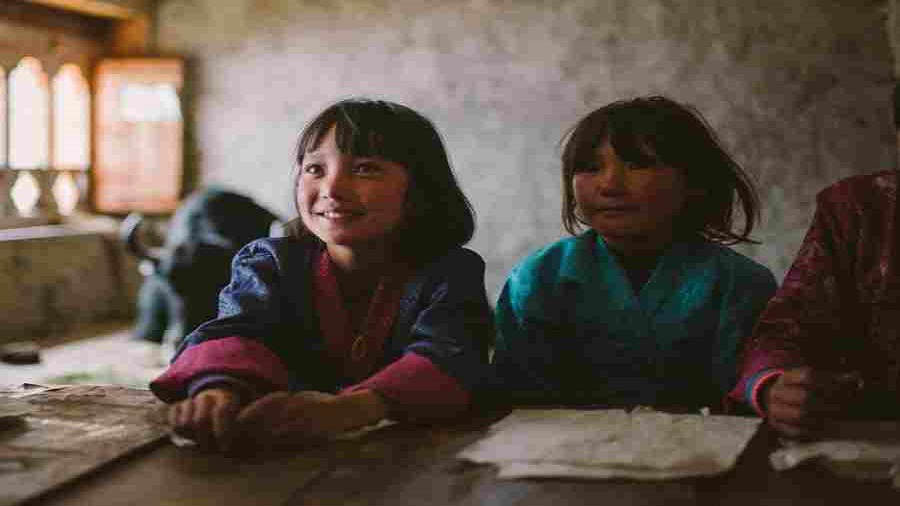

Fans and supporters of South Asia’s film industry have a reason to smile. The Cannes Film Festival last week delivered a vote of confidence for films produced by the world’s most densely populated region. Even though the topmost honours eluded the region’s nominees, Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes won the Golden Eye, also known as the L’Oeil d’Or, after being chosen as the best documentary by the jury. The film tracks the journey of two Muslim brothers in New Delhi who rescue injured birds, and its success follows last year’s win by fellow Indian, Payal Kapadia, for her documentary, A Night of Knowing Nothing. Meanwhile, Joyland, a bold feature film about a conservative and patriarchal Pakistani family that must confront the addition of a transgender member, won a jury prize and Lori, a Nepalese film, won a Special Mention Award. The recognition for these films comes close on the heels of the Oscar nomination for the Bhutanese film, Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom, earlier this year.

But despite these achievements, the film industries in India and across South Asia are some distance away from garnering the global acclaim that South Korea’s moviemakers, for instance, have received in recent times. That films not just from India but also from Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan are getting noticed internationally is good. Still, given the disproportionate resources and clout that they command in comparison to their peers in other South Asian nations, it is Bollywood and India’s regional film industries that must shoulder the principal responsibility for breaking through globally the way Korean movies have done. The challenge? Far too often, and for far too many in India, movies are a method of escapism from the struggles of life. There is no denying the need for cinema to reflect the demands of their audiences. But Indian films have ably demonstrated over the years that there is a market for both of what are colloquially known as ‘mainstream’ and ‘alternative’ cinema.

The selection of films for the festival by Cannes juries offers clues to how Indian moviemakers could regain that balance. The Satyajit Ray classic, Pratidwandi, was among the movies chosen for a screening in the ‘classics’ section of the festival. Indian filmmakers who want to make a mark the way that South Korea’s Bong Joon-ho made with Parasite should consider returning to the neo-realist tradition of filmmaking that Ray pioneered in the country. That will not be easy in a climate where the equation between the political elite and independent filmmakers is very different from the times of Ray, who enjoyed the patronage of Indira Gandhi even though he never flinched from showcasing India’s myriad challenges. Today, the Indian State appears to believe that the film industry must portray either a triumphalist nationalism or point fingers of criticism at past governments. Films that meet these criteria — even if they falsify history — receive tax benefits and government promotion. Unless the Indian movie industry is careful, it risks being lulled into a coma of mediocrity.