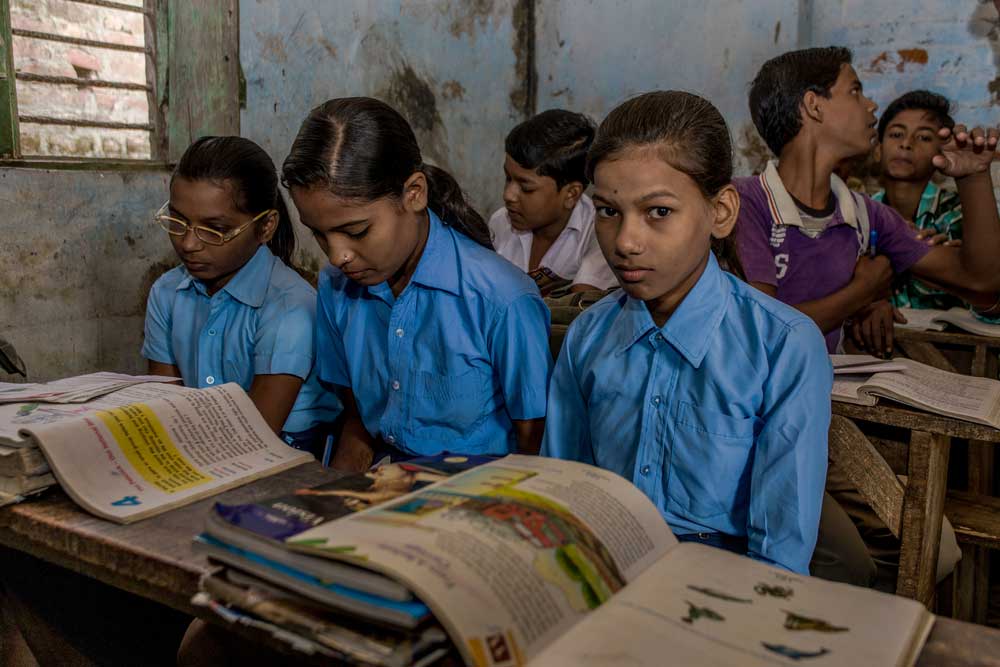

All work and no play does boys and girls no good; nor does having to do all that work in discomfort, or in the dark. And yet, these seem to be the sort of conditions that the students of more than 40 per cent of the nation’s government schools have to suffer. A parliamentary panel on education recently revealed that almost half of India’s government schools have neither electricity nor proper playgrounds. The panel also chided the government for its “dismal” rate of progress in building classrooms, libraries and laboratories to modernize higher secondary government schools. The figures speak for themselves: out of 2,613 projects sanctioned for 2019-20, only three had reached completion in the first nine months of the financial year. Is it any wonder, then, that the learning outcomes in schools are appalling, as identified by the recent Annual Status of Education Report, with students in government-run schools faring significantly worse than those in private institutions?

All of these figures, along with the revelations of the parliamentary panel, point to a marked lack of focus on building robust infrastructure, which is a key facet in education. The ambitious Saubhagya scheme was launched by the prime minister in 2017 with a pledge to electrify all Indian households. While the success of this venture is debatable — the power supply in rural areas remains highly unreliable, state-owned electricity distribution companies are in the financial doldrums and the government has been repeatedly accused of manipulating figures to meet target deadlines — it must also be noted that institutions as important as schools are not included within the ambit of such public utilities. Given that the parliamentary panel also highlighted shortfalls in funding and utilization as causes for such severe lapses in infrastructure, would it be unreasonable to infer that such lapses are not entirely unintentional? The paucity of playgrounds might bolster this suspicion. Recreation is fundamental to all-round education. As such, the fact that less than 57 per cent of schools have them suggests a dogged refusal to move away from an orthodox education policy that only prioritizes studies and rote learning over leisure and recreation. A modern school system, which should be a top priority of the State, will be impossible to put in place without electricity and recreational facilities. The political will required to achieve this, however, is conspicuous by its absence.