‘We did it. We turned the European Union into a giant able to hold its own in a world of giants such as China and the United States.’ In the summer of 2027, as the French president, Emmanuel Macron, looks back on his recently completed decade in office, will he be able to say this? A lot will depend on who he means by ‘we’.

‘European sovereignty’ is Macron’s term for being a giant in a world of giants. Strategic sovereignty involves not being dependent on Russia for your energy, the United States of America for your security, and China for your corporate profits. It’s having a European foreign and security policy muscular enough to deter aggressors like Vladimir Putin, even if the US has re-elected Donald Trump in 2024.

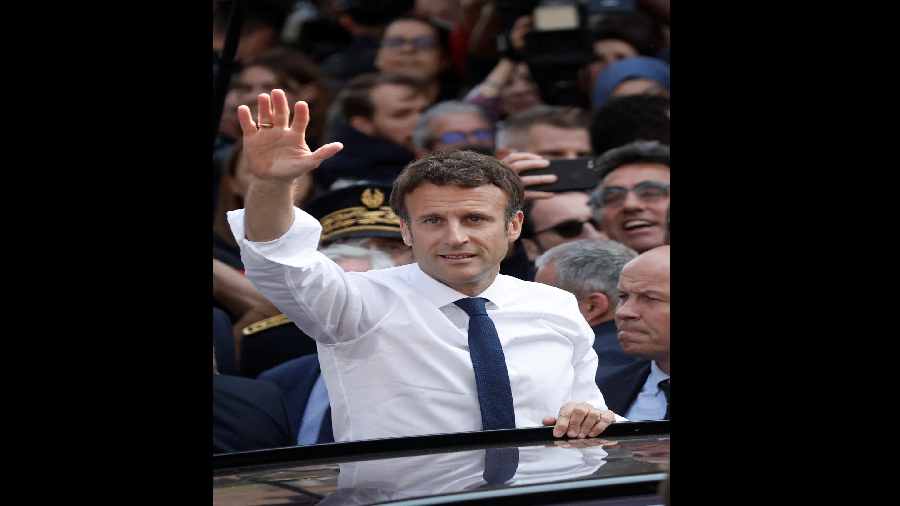

It’s also not relying entirely on others for your microchips, AI and digital platforms. In short, it’s a very long way from where Europe is today. Macron is currently the only major European leader with the vision, ambition and experience to move the Union decisively in this direction, but the obstacles are enormous. One of them was in plain view in the recent presidential election with the high levels of abstention and support for Marine Le Pen, his nationalist, nativist opponent. Macron has the faults of his virtues. I have never seen a human being with more drive, ambition, energy and self-belief. But he can often seem arrogant, Jupiterian, neo-Napoleonic — and, therefore, rub a great many of his compatriots and fellow Europeans up the wrong way.

Macron’s ‘we’, all too often, sounds like the royal ‘we’, meaning ‘me’. To adapt Louis XIV: “L’Europe, c’est moi”. He does know that he needs Germany. His first official visit after his inauguration in the second week of May will be to Berlin. Europe is, once again, to be led by the Franco German ‘couple’. He will find in the German chancellor, Olaf Scholz, a more willing partner than Angela Merkel ever was. Scholz has already made strengthening the EU a central plank of his programme. The dry, understated Scholz is going through a very bad patch at the moment, seemingly incapable of finding the words, tone and decisive speed of action needed to respond to the largest war in Europe since 1945. In this, he is the diametric opposite of the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky. Zelensky was a rather ineffective peacetime president but has turned into a superb wartime leader. Scholz was shaping up to be a first-rate peacetime leader. In the first days of the war, he seemed decisive, introducing a new German word into the English language: zeitenwende (epochal turning-point). But since then, he has been always on the back foot over German energy supplies from Russia and weapons supplies to Ukraine. Getting together with Macron is an opportunity for him to make a European reset. One of the first things they should do together is to pay a joint visit to Zelensky in Kyiv.

Yet, in today’s EU of 27 member states, the Franco-German couple alone is not enough. Europe’s ‘we’ cannot be just a combination of French nous and German wir. Fortunately, they have some excellent colleagues on hand. The Italian prime minister, Mario Draghi, has, unlike Scholz, skilfully made the transition from peacetime economic manager to the sharper, bolder style of leadership required in times of war. Heads of government, such as Pedro Sánchez in Spain, Mark Rutte of the Netherlands, and Kaja Kallas of Estonia, are serious partners for a broader European ‘we’. Europe always works best when you have coalitions of the willing among national governments supported by the Brussels institutions. (If the British Conservative Party would finally summon up the decency and courage to get rid of Boris Johnson, the EU might also have a strategic partner across the English Channel, at least on issues like security, energy and environment.) The EU’s longest-serving head of government, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, is a problem. The good news is that the Hungarian strongman keeps losing support in central Europe. On the day of the French election, Slovenia voted out another of Orbán’s populist allies, Janez Janša. And Orbán badly needs EU funds that are currently being held back. So Macron, Scholz and their colleagues just need the gumption and the guts to tell him exactly where he can put his threatened veto of further sanctions on Putin’s Russia. Behind the collective action problem that the newly re-elected French president faces in the EU is a deeper challenge clearly visible in his own country.

Even where the policies of the EU are already European, the politics are still national. To a greater or lesser extent, all Western democracies are being roiled by nationalist, anti-liberal, anti-centrist politics of the kind represented in France both by the far-Right of Le Pen and the polemicist, Éric Zemmour, and by the far-Left of Jean-Luc Mélenchon. (Among them, those three candidates got 52% of the vote in the first round of the French presidential election). If you add together the 13.3 million people who voted for Le Pen in the second round, the 13.6 million who abstained and the 2.2 million who submitted blank ballot papers (a form of protest vote), you get a figure roughly one-third larger than the 18.8 million who voted for Macron.

Macron faces a parliamentary election in June and it is far from clear that his République En Marche party can secure a working majority. According to current polling in Italy, the right-wing, populist Fratelli d’Italia and Lega would between them have about 38% of votes and so could potentially form the Italian government after a parliamentary election. This widespread unhappiness with the liberal centre and ‘Europe’ is a result of many causes. They include long-term social and cultural effects of the concentrated form of globalization represented by the EU; the fact that after the 2008 global financial crisis, the rich generally emerged richer and the poor poorer; the subsequent economic impact of the Covid pandemic; and now the war in Ukraine, pushing energy prices and, hence, the cost of living further through the roof. The worst is yet to come. If the domestic politics in just a couple of EU member states go the wrong way again, Macron’s European agenda will be even more difficult to achieve.

Watching this extraordinary man, I am always reminded of Jacques-Louis David’s heroic picture of Napoleon crossing the Alps on a prancing white steed, one arm outstretched to point the way onward and upward. The reality is going to be more like an ill-disciplined tour group driving slowly up the mountain in a gaggle of electric cars — and the car in front will not always be a Renault.

(Timothy Garton Ash is Professor of European Studies at Oxford University and a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University)