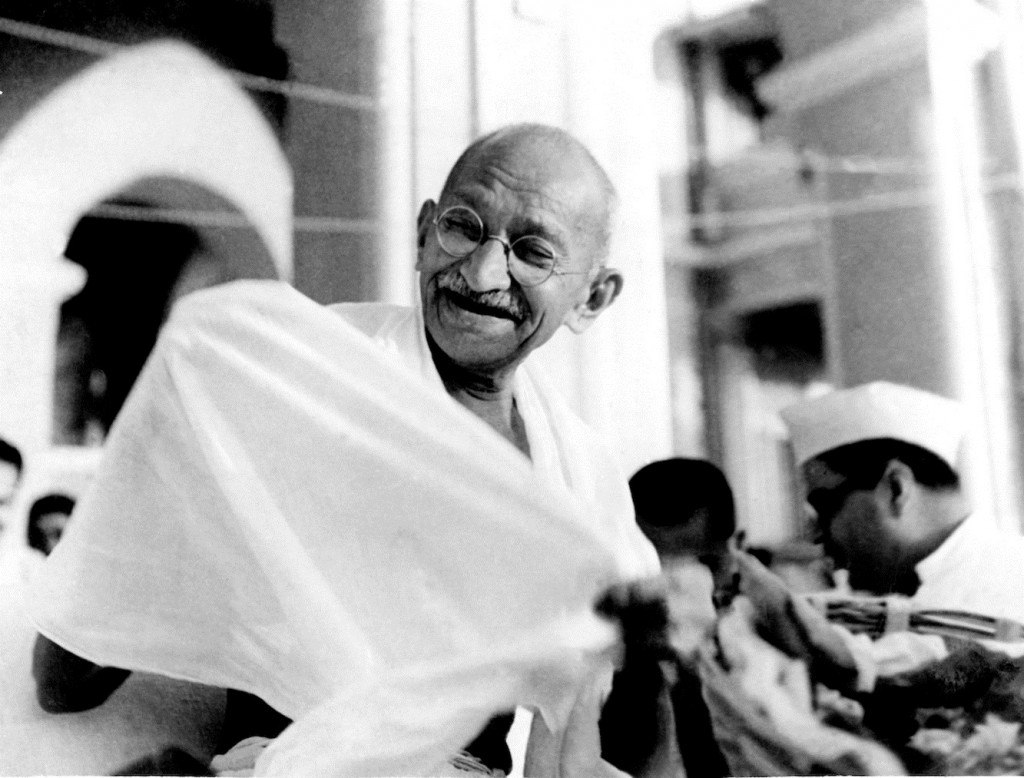

The 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi is being commemorated all over India in programmes big and small. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has accorded exceptional importance to the event and is sparing no effort to ensure that it is observed on a grand scale both in official and political programmes. The Bharatiya Janata Party has initiated an ambitious programme of padayatras in every parliamentary constituency of the country, not least because it offers an opportunity for mass contact. By contrast, the Congress, which once held a copyright over the Mahatma’s legacy, has been more modest in its approach, confining itself to seminars and encouraging its many intellectual sympathizers to write op-ed articles that simultaneously question the right of the BJP to lay any claim on the Gandhian legacy. This modest approach is not because it lacks commitment but because the party is in the throes of an existential crisis following its severe defeat in the 2019 elections.

Needless to say, there is a definite political dimension to the Mahatma@150 commemoration, and this is best reflected in some of the debates on the theme. Since its very inception, the Jana Sangh/BJP has faced accusations of being more wedded to the legacy of Nathuram Godse rather than that of Mahatma Gandhi. While this charge is more applicable to the small fringe that exists around the letterhead of the Hindu Mahasabha — the present Mahasabha bears little relationship to the body that played a significant role in national politics prior to 1947 — the BJP has always been at the receiving end of taunts. However, this apart, what is striking about the Mahatma@150 commemoration — as opposed to the Mahatma@100 commemoration in 1969 — is the growing acceptance of the facets of the great man.

The earlier scepticism is worth recollecting.

In 1969, the legacy of the Mahatma was definitely more contested. The Left — far more relevant intellectually in 1969 than it is today — always found it difficult to reconcile Gandhi’s near-fanatical commitment to non-violence with its own celebration of revolutions that had a generous share of violence, whether in Russia, China, Cuba or Vietnam. To this was added the belief, articulated so succinctly by the British communist, Rajani Palme Dutt, in his India Today, which was obligatory reading for all Communists till the early-1980s at least. Palme Dutt, who was the guiding spirit of the Communist Party of India from London — the Indian communist movement was run by the ‘colonial department’ of the Communist Party of Great Britain —called Gandhi the “Jonah of revolution, the general of unbroken disasters,… the mascot of the bourgeoisie” and berated him for trying to “find the means in the midst of a formidable revolutionary wave to maintain leadership of the mass movement.”

The Left-inclined also devoured the thin volume of E.M.S. Namboodiripad’s searing critique of Gandhi — including his faddish obsession with vegetarianism — in The Mahatma and the Ism. To this was added the empirical research of contributors in the early volumes of Subaltern Studies that sought to highlight the rich tradition of struggles that took place on the periphery of the Gandhi-led movements but had a logic and momentum of their own. Implicit in these assessments was the belief that Gandhi’s impact was overrated and, where it existed, acted as a brake on the self-expression of the anti-imperialist struggle.

Bringing the Mahatma down many notches was undeniably one of the foremost objectives of the Left although there were some exceptions to this trend. It is no accident that when the impetuous Naxalites who weren’t inhibited by constitutional and parliamentary niceties chose to emulate China’s misplaced Cultural Revolution on the banks of the Hooghly, the statues of Mahatma Gandhi were among the most favourite targets of vandalism.

In a curious sort of way, this disavowal of the man who was elevated to being the Father of the Nation struck a chord in Bengal. As Bengal struggled — mostly unsuccessfully — to cope with its growing economic and political marginalization in Independent India, it became customary for a particular brand of crotchety Bengali to grandly proclaim that the Mahatma was anti-Bengali, as indeed was Jawaharlal Nehru and the rest of the post-1947 Congress leadership. To some extent, this was a consequence of the factional battles within the Congress that saw Gandhi throw his entire political and moral weight behind the moves to cripple Subhas Chandra Bose as Congress President in 1939. Bose had the political audacity and resolve to take on the Mahatma’s lieutenants in the provinces; he could even stare down the likes of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, C. Rajagopalachari and Rajendra Prasad. But he couldn’t match the moral and political authority of Gandhi himself.

In 1939, Bose resigned as Congress President as a very bitter man. Much of that bitterness rubbed off on the Bengali middle classes, many of whom began perceiving Gandhi as a wily Gujarati bania whose saintliness was a façade. But while Bose’s differences with Gandhi stemmed from reasons that were grounded in both politics and temperament, many Bengalis chose to view them as evidence of cultural antipathy towards Bengalis.

This irrational conclusion had been some time in the making. It is today a forgotten chapter but the reality was that Gandhi’s rise to the top of the Congress pile in 1920 was made possible by his victory over Chittaranjan Das, a man who represented the forces of constitutional nationalism. At that time, Gandhi, with his talk of cloth-burning, boycott of the courts and educational institutions and advocacy of vegetarianism and non-violence, struck many Bengalis as plain antediluvian. It didn’t bolster the Bengali perception of Gandhi that among his chief backers in his battle to gain control over the Congress were the moneyed Marwaris of Calcutta.

This wariness of Gandhi was also coupled with the deification of the revolutionary movement. Gandhi was uncompromisingly opposed to all forms of violence in the movement for independence. Whether this was strategic or born out of his ethical convictions may well be debated but the net result was that it brought about an emotional gulf between him and the Bengali, Hindu-educated classes. Even the Congress had to take note of this gulf, a reason why the two main factions of the Bengal Congress — one led by the Big Five that included Subhas Bose and his elder brother, Sarat Bose, and the other by J.M. Sengupta — had alliances with the two main revolutionary groups, Jugantar and Anushilan. There was a small Gandhian group but its influence was severely limited, except perhaps in Midnapur district.

This ambivalence towards Gandhi and his legacy still persists but in a much more limited way. Today, different political persuasions are anxious to internalize, if not appropriate, the varied messages from Gandhi’s life. The Left has shed its hostility to the man who undercut the ‘revolution’ and has teamed up with the Congress to stress Gandhi’s multi-faith credentials. The Muslim community which, before Independence, painted Gandhi as exclusively a ‘Hindu’ leader, now see him as a secular icon. On his part, Modi has firmly buried the old Hindu Mahasabha critique of Gandhi and has enthusiastically embraced facets of his ‘constructive programme’ in the Swachh Bharat campaign, particularly the construction of toilets. In Bengal, the greenhouse of political violence, Gandhi as the apostle of non-violence is suddenly beginning to make sense. Facets of the old Gandhiji-Netaji tussle still linger in the state but much of this has also been subsumed by positing Netaji against Jawaharlal Nehru in an imaginary post-1947 scenario. Only the old Ambedkarite critique of Gandhi as the man who united Hindus without addressing the contradictions of the caste system still persists.

In the past 50 years, between 1969 and 2019, India’s celebration of the man who was unquestionably the leader of the freedom struggle and exercised both political and moral authority has undergone a shift. This is a pattern that will persist. By the time Gandhi@200 approaches, the Gandhi of history may well be juxtaposed to a Reinvented Gandhi.