Mahatma Gandhi visited the Valley of Kashmir once, in the first week of August 1947. He was then 77, and the journey was arduous, but personal duty and national honour both called him there. His country was about to be freed, and divided; it was not clear which way the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir would go. While the population of the state was mostly Muslim, their popular leader, Sheikh Abdullah, detested Pakistan as he was a thoroughgoing secularist himself. The ruler of the state, Maharaja Hari Singh, was a Hindu, but he did not want to join either India or Pakistan, nurturing the fantasy of creating a sort of Eastern Switzerland instead with himself as its presiding deity.

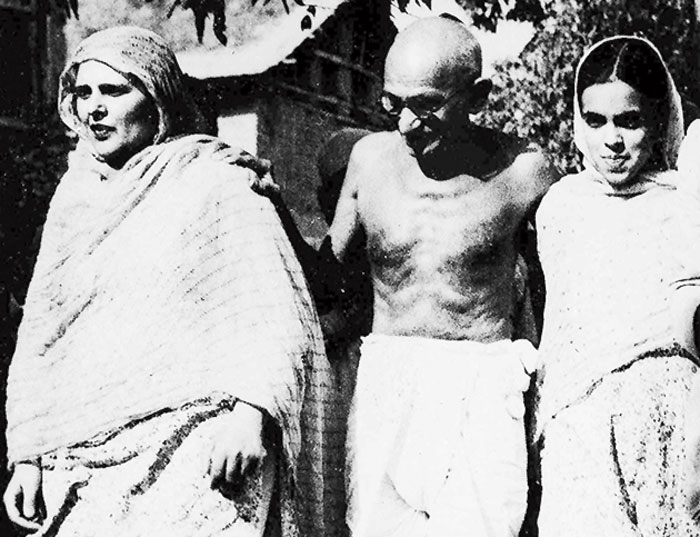

Gandhi’s trip had two main aims; to get the Maharaja to release Sheikh Abdullah from prison, and to get a sense of what the people of Kashmir were thinking. When he reached the Valley he received a terrific reception. On his entry into Srinagar he was met by thousands of people on either side of the road, shouting “Mahatma Gandhi ki jai”. Since the bridge across the river Jhelum had been taken over by the crowd, Gandhi took a boat to the other side, where he addressed a public meeting of some 25,000 people, convened by Sheikh Abdullah’s wife. He spoke of spiritual rather than political matters, in Hindustani. His doctor Sushila Nayar, who was with him, wrote that “men and women flocked from the neighbouring villages to have a glimpse of the Mahatma. Friends and foes alike wonder at the hold he has on the masses. His mere presence seems to soothe them in [a] strange fashion”.

Gandhi spent three days in the Valley and two days in Jammu. In a short note on his Kashmir visit, that he sent both to Nehru and to Patel, Gandhi wrote of his conversations with the maharaja, Hari Singh, and his son, Karan Singh. He remarked that “both admitted that with the lapse of British Paramountcy the true Paramountcy of the people of Kashmir would commence. However much they might wish to join the Union, they would have to make the choice in accordance with the wishes of the people. How they could be determined was not discussed at that interview”.

Although Sheikh Abdullah was in jail, other leaders of his National Conference were not, and Gandhi met them too. He later wrote to Nehru and Patel that these National Conference leaders were “most sanguine that the result of the free vote of the people, whether on the adult franchise or on the existing register, would be in favour of Kashmir joining the [Indian] Union provided of course that Sheikh Abdullah and his co-prisoners were released...”

Gandhi spent India’s first Independence Day not in Delhi but in Calcutta. He was in no mood to celebrate because of the wave of Hindu-Muslim rioting that was sweeping across India. By his own example and through his fasts, Gandhi single-handedly stopped the violence in Calcutta, and then proceeded to Delhi, hoping to do the same there.

In late September, the Maharaja released Sheikh Abdullah from prison. Three weeks later, Pakistan invaded Kashmir, seeking to forcibly annex the state. The Sheikh took the lead in mobilizing the people against the raiders. Hearing about their courage, Gandhi said, at his prayer meeting in Delhi on October 29, 1947: “Kashmir cannot be saved by the Maharaja. If anyone can save Kashmir, it is only the Muslims, the Kashmiri Pandits, the Rajputs and the Sikhs who can do so.” Gandhi noted, admiringly and significantly, that “Sheikh Abdullah has affectionate and friendly relations with all of [these communities]”.

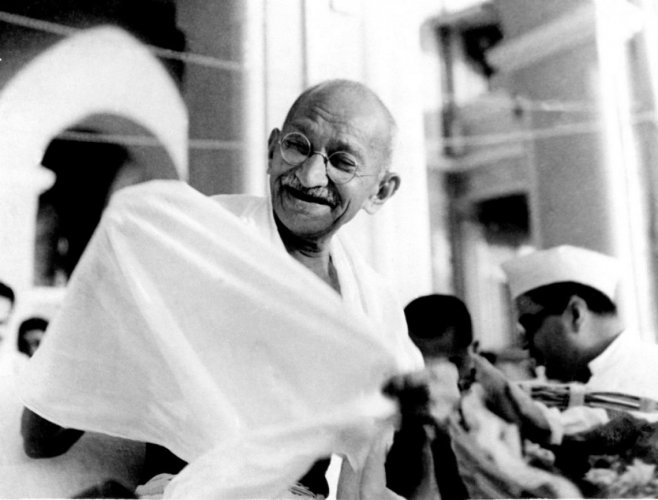

A month later, with the Indian army now fully in charge of repulsing the raiders, Sheikh Abdullah came down to Delhi. At Gandhi’s prayer meeting of November 28, the Sheikh stood next to him, where the Mahatma said: “Sheikh Abdullah had done one great thing. He had kept the Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims united in Kashmir and created a situation in which they would wish to live and die together.”

Two months later Gandhi was murdered, by a Hindu fanatic. In the seven decades since, Kashmir has lurched from crisis to crisis, with State repression combining with religious fanaticism to make this most beautiful part of India also the most strife-torn. Had Gandhi been alive, he would perhaps have been most appalled by three events in the modern history of Kashmir: the arrest of Sheikh Abdullah by the Nehru government in 1953, the ethnic cleansing of the Pandits by Islamic jihadists in 1989-90, and the unilateral abrogation of Article 370 and the savage crackdown by the Narendra Modi government on Kashmiris in 2019. The last especially would have horrified him; that, in the 150th anniversary year of his birth, an Indian government had refused to “make the choice in accordance with the wishes of the people”, and, instead, made the Valley into the largest open-air prison in human history.

To be sure, Gandhi is not around to comment on current affairs in Kashmir. But some who speak with some credibility in his name are. I have just received a statement on Kashmir issued by the Gandhi Peace Foundation, an independent body set up in 1959 to commemorate the Mahatma’s memory, and which has done good work since. Younger readers may not know that the great Jayaprakash Narayan was closely associated with the GPF. Like him, it courageously opposed the Emergency, and was hounded by Indira Gandhi on her return to power in 1980 as a consequence.

The GPF’s statement is issued both in Hindi and in English. It says: “The gun that was used to silence Kashmir is now being used as a telescope through which to see Kashmir. This is shameful, unfortunate and ominous for India.” It continues: “‘A whole state has vanished from the map in broad daylight. The Indian Union had 28 states, now it has 27. This is not a magic show, where a magician shows us, we know, something unreal and illusory. Here we are witnessing something cruel, ugly, undemocratic and seemingly irreversible. It reveals the poverty of our democratic politics.”

Of the sham conducted in the ‘Hall of the People’, the statement says: “What took place in the Parliament this time was far from an exchange of views or a serious debate. One man shouted, more than three hundred thumped desks, and the rest sat crestfallen, defeated. This is not bahumat or majority, but bahusankhya or majoritarianism — an attempt to rule by numbers.”

The GPF warns us: “We will not be able to lock down Kashmir forever. The doors will surely open, the people will come out, and their anguish will burst forth. Foreign elements will poison their minds with even more vigour. All the leaders of the opposition who were urging the people to maintain peace and abide by the rule of law have been imprisoned. We have burnt all the bridges for a possible dialogue.”

The statement from the GPF ends with this exhortation, addressed both to ordinary Indians and to the government: “We must stand with the Kashmiris in their hour of crisis, which is equally our hour of crisis. Our helpless fellow-citizens who have been imprisoned must know that all right-thinking Indians share their anguish. The government must protect law and order, but it must also allow free expression at every level. That will help us to normalize the situation.”

As someone who has studied Gandhi for many years, and soaked himself in his writings, I believe the GPF statement is absolutely in line with what the Mahatma would have thought about the tragic happenings in Kashmir now. Let us recall the remarks Gandhi himself made in 1947: “Kashmir cannot be saved by the Maharaja. If anyone can save Kashmir, it is only the Muslims, the Kashmiri Pandits, the Rajputs and the Sikhs who can do so.”

The power-hungry political maharajas of today who pretend to be Kashmir’s saviours cannot save Kashmiris. Nor can the avaricious corporate maharajas toadying up behind them. Nor indeed can the Pakistani army or their proxy jihadists, who have cynically brainwashed so many Kashmiri young men over the decades and sent them to their tragically early deaths.

Given its geographical location and the burdens of history it carries, it may be that Kashmir is condemned to many more decades of conflict and bloodshed. But those Indians — Kashmiris included — who have not turned their back entirely on the teachings of the Father of the Nation must not stop trying. Truth in speech and writing, reason in debate and argument, non-violence in action, an absolute commitment to inter-faith harmony in everyday life — these ideals and principles must be kept alive in these dark times too.