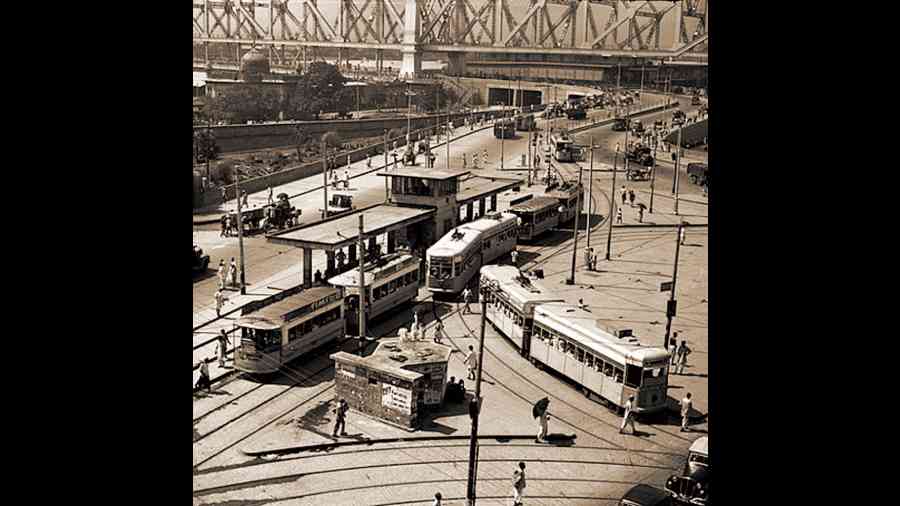

On the 150th anniversary of the arrival of tramways in Calcutta, here we are, once again, going around the circuit of the old debate. Argument Pro: trams are wonderful; so many great cities of the world have extensive tram systems; Chennai and Bombay were downright foolish to have got rid of their trams and Calcutta was ill-advised in reducing its tram network and we need to re-install it. Argument Con: trams are now an anachronism and we need to get rid of the things; Calcutta is too crowded, the transport needs too critical, and the streets too narrow for trams to be accommodated out of some nostalgia or fuzzy notions of ecology; the way forward is the metro and electric buses. An appendix to this latter argument is, ‘Okay, we can have a tram loop around the Maidan so that tourists can get their fill of heritage, but no more than that.’

I am not a Calcutta tram nostalgist. Calcuttans of my generation were around when a lot of the great tram sequences were filmed by Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and others: the connector rod flicking overhead from wire to wire, the protagonist sweating in the tram, jumping off and lighting a cigarette, the clanking, jerking view of the streets from the windows — it’s all there, both in our cinema-memory and the actual memory of taking trams. In the multi-level hell that was (and, to a certain extent, still is) the Calcutta public transport universe, even among the jampacked L9s, 47As and ‘Leggadenz to Beebdibag’ minibuses, the trams stood out as a particularly tortuous circle of the sweaty inferno. Being caught behind one of the geriatrically hobbling contraptions while sitting in a bus was no fun either. A typically depressing chakravyuh was when you were in a tram and it got into a tangle with rikshas and thhelas under the burning sun — entrapped by these seemingly archaic modes of transport, you could only be in one place aka The City of Noy, as in ‘eita kono metropolis noy, eita 20th century noy — na kono movement, na kono future, na kono chance.’

Calcutta needs trams — not the old trams revamped nor just a refurbishment of the old routes but a whole new and extensive modern tram system. People who blindly worship the idea of new things could even be allowed to think that this is something totally fresh and cutting edge that is being introduced to the city, something that no other Indian city has. The planning and construction of this tram system cannot come about in isolation — it has to be part of a radical new plan to totally rethink Calcutta’s public spaces and its transport grid.

At the core of this plan has to be the understanding that an overwhelming majority of Calcutta’s denizens travel on their feet; most of the millions living here walk out from their dwelling into the street; they take a local train or a bus, or a combination of train and bus; they get off and walk to their place of work; at the end of the day, they repeat the journey in reverse. Besides them, there are hundreds of thousands of people who use bicycles, not for pleasure or exercise but as a basic means to go about their daily working life. In a city such as this, the rampant, unchecked use of the private motor-car, a habit that captures most of the available road space for a small minority, is not just counter-productive, it is nothing short of craziness. The plan has to work towards making the city safe and comfortable for pedestrians and cyclists, but not just that — the plan has to work towards pedestrianising the city, bringing about a change of habit so that even most car-owners make public transport their first choice and drive only rarely inside the city limits.

We have to develop the courage to imagine a city where the private car and, especially, all fossil-fuel-powered vehicles are dwindling into the margins and then to actually make this happen. We have to turn large sections in the centre of the old city and the newer areas into attractive, pedestrian-only zones. We have to make sure there are electric and CNG buses of different ticket-levels that work in partnership with the Metro and the tram system, where the crazy brawling of buses desperate to grab passengers is a thing of the past. We have to think of alternatives to the free-for-all of the auto-rickshaws — other vehicular means that deliver the transport needs the autos currently fulfil — while providing employment to the current drivers. We have to think of alternative spaces from where the city’s millions of street vendors can earn a living without gobbling up the sidewalks.

It is as part of this plan that one can think of a new tram system for the city. Obviously, many of the original routes would be resurrected but we should put most images of the old CTC trams out of our minds. Imagine, instead, the line from Tollygunge to Esplanade, the trams rolling along a dedicated raised corridor, not in the centre but on the western side of the road, adjacent to the stall-free sidewalk. Imagine then two lanes, up and down, given over entirely to buses (no overtaking allowed) and then a narrower, protected bicycle-only lane on the eastern side of the boulevard. Where do the cars go, you ask? They don’t: only ambulances and other emergency vehicles are allowed to use the bus lanes. If you are willing to pay the huge daily charge for driving into central Calcutta and its strictly limited parking, you will have to use other routes, the two or three designated north-south roads where speeds are strictly monitored and where the many pedestrian crossings (again firmly policed) mean that you will take much longer to get to Dalhousie/BBD Bag than you would with a combination of Metro, bus and tram.