Annie Besant — she died in September 1933 — is venerated, globally, as one of the leading proponents of Theosophy. The Theosophical Society was founded in 1875 with the objective of disseminating the wisdom of the Theosophists — thinkers whose roots go back to the Neo-Platonic philosophical tradition — who propounded the ideal of universal brotherhood through the fusion of diverse philosophical thoughts, including Vedanta, Buddhism and Sufism. Besant’s association with the Theosophical movement has somewhat clouded her pioneering role in distinctly earthly spheres. She was an advocate of Self Rule (for Ireland and India) and passionately endorsed freedom of thought, union mobilization, birth control. These accomplishments may not have receded completely from public memory. But what is often forgotten is another seminal, secular imprint left behind by this remarkable woman: Besant started India’s first course in print journalism, over one hundred years ago, at the National University at Adyar, Madras. The course may not have lasted for long, but journalism education continues to thrive in India, with an estimated 900 institutions of unequal repute offering degrees and programmes in print, television and, now, digital media.

The importance of pedagogy in journalism as a discipline has been reinforced — ironically — by the crises that plague modern media. The challenges vary across media platforms. Print media remains locked in an existential crisis brought about by the drain of revenue in favour of such new avatars as digital news outlets as well as social media masquerading as providers of news. Television journalism in India — wedded to pageantry — is contending with the paucity of serious, cerebral content. Digital news, meanwhile, is having to battle State encroachment, as is evident from the legal challenges mounted in defence of free speech against the tentacles of the predatory Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021.

Some of the threats, however, are common to all segments of the media fraternity. Economic gloom, the grovelling by the ‘free press’ at the feet of authoritarian regimes — Hungary, Russia and India remind us that this ignominy has come to pass — and the triumphant march of that other pandemic — disinformation — have eroded the media’s credibility. But none of these challenges, Ian Hargreaves reveals in his excellent book, Journalism: Truth or Dare, is new. Some of these threats, Hargreaves writes, germinated in the 1990s but the media and their stakeholders — proprietors, investors, editors, journalists — are yet to find a way to neutralize them. The tenacity of the crises, the Unesco said recently, reinforces the need to recalibrate the module of journalism education. Hopefully, journalism schools, in India and around the world, are striving towards this goal.

This column, though, isn’t about journalism’s meta-crises. It concerns itself with seemingly mundane dilemmas that confront human beings in general but print journalists in particular. These predicaments that scribes would relate to, Eric Weiner demonstrates in his witty and erudite The Socrates Express, are not as trivial as they appear: they have engrossed some of the world’s foremost philosophers on account of their deep moral underpinnings.

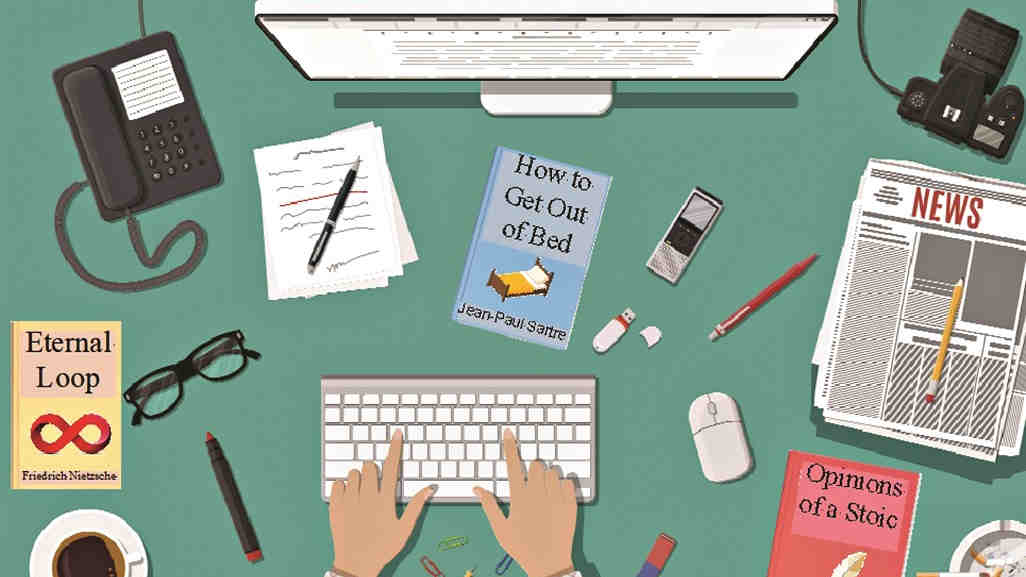

No journalist worth his/her salt is a morning person. The trouble with getting out of bed — Philosophy’s Great Bed Question — has stirred the philosophical hornets’ nest, with Marcus Aurelius, the Roman philosopher-king, David Hume, the enlightened Scottsman, Jean-Paul Sartre, the surly Frenchman, dwelling on the horrors of the rise-and-shine dictum. The bed, they say, offers the fleeting promise of repose and shelter from the harshness of reality. Strikingly, in this context, the end — for journalist and philosopher — is the same: to rouse the sleepy soul out of this comforting cove. The difference lies in the means that they employ: the philosopher gets us up and running by reminding us of the ticking clock called mortality; the intrepid reporter hauls readers up with the, albeit increasingly rare, riveting story.

Apparently, the human attention span has now fallen to a mere eight seconds. This corresponds to the sordid reality of factual howlers that get printed or are aired as news. Help, once again, is at hand for the somnolent, distracted or overworked editor. The trick, says Simone Weil, mystic, philosopher and activist, is to imagine attention not as a technique, a mere cognitive mechanism, but to perceive it as a virtue, a tool for empathy. René Descartes, Weiner writes, had settled the debate earlier, elevating attention to an “intellectual divine rod” that sieves clear ideas from dubious ones — in our world and that of the editor, that would imply the critical task of filtering the false from the true.

Popular culture’s prototype of the journalist may be a pretty face in pin-stripes thrusting a dictaphone in front of a startled respondent at every given opportunity. But real, as opposed to fictive, journalistic work involves, at least for the occupants of the lower echelons of newspaper production, back-breaking, relentless, usually underpaid, almost invisible, and inevitably repetitive labour. The minions — say, the subeditor — may, at times, go unnoticed by the higher-ups but Friedrich Nietzsche had spotted them alright: his concept of the Eternal Recurrence of the Same, in which life recurs infinitely in a loop, seems to mirror and — most importantly — dignify the life and labour of those who bring a newspaper to life every single day.

And how should the embattled newspaper personnel — owner, editor, reporter, subeditor et al — endure this sameness? They could try reading Epictetus. For Stoicism, the philosophical school that Epictetus belonged to, reminds us, in Weiner’s words, “[m]uch of life lies beyond our control but we command what matters most: our opinions…”

In these tumultuous times of dipping revenues, formidable commercial rivals, a surveillant State and the pandering to Untruth, this could well be philosophy’s most important gift to journalism.

Annie Besant — that philosopher-journalist? — would agree.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in