Stone walls do not a prison make; or so wrote an incarcerated British poet years ago. While the mighty State may fetter the body, it often discovers that it is far more difficult to chain the mind. A booklet containing artwork and excerpts from letters by two university students jailed for their alleged involvement in the Delhi riots seems to attest to the uplifting resilience of freedom. With their accounts detailing institutional attempts to strip them of their “autonomy” and “humanity”, Devangana Kalita and Natasha Narwal may now find themselves to be part of an illustrious literary tradition of prison writing that has, over the years, given voice to thoughts and lives behind those walls. The repository of prison writings comprises contributions from such luminaries as M.K. Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Nelson Mandela, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Antonio Gramsci, to name a few. Each of these towering figures had turned to writing during their periods of isolation.

The richness of this genre can be attributed to the versatility of thought. Don Quixote’s flights of fancy were imagined by Miguel de Cervantes from inside his solitary cell; Nehru penned his encyclopaedic The Discovery of India from inside the Ahmednagar fort; in more recent, post-colonial times, Chris Abani documented his shackled life in Kalakuta Republic. A common theme among these works is the documentation of the illuminating tussle between the State and the captive political prisoner over the autonomy — as Ms Kalita and Ms Narwal put it — of the mind. History has shown that writing has often been the only weapon in the arsenal of the conscientious prisoner to resist the colonization of his or her mind. Little wonder then that Michel Foucault called prison writing a ‘habeas corpus brief’: such texts or, as is often the case, doodles invert and challenge the collective ideas concerning the relationship that binds the State to the citizen, exposing the former’s role in creating penitentiaries meant to discipline, often brutally, the dissenter.

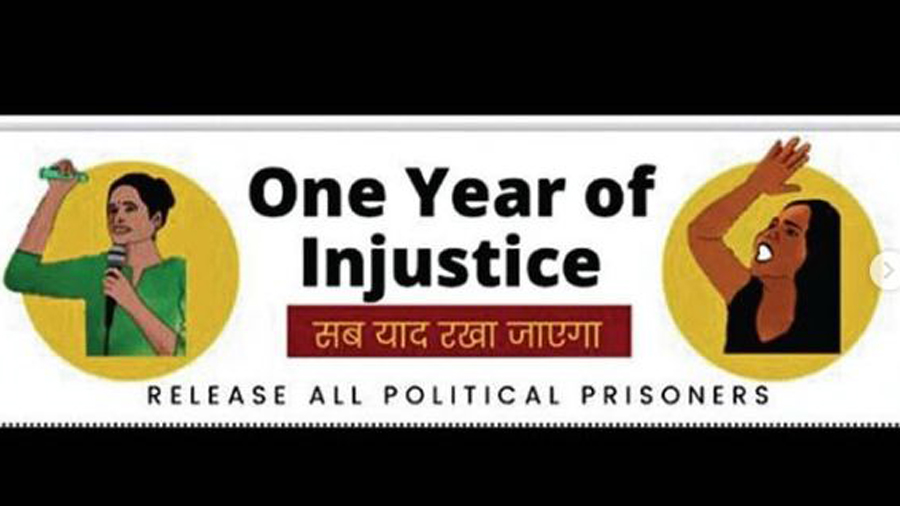

The pursuit of civilizing not just the ‘savage’ but also the objector with integrity continues to inform justice and such affiliated institutions as prisons. This is an anomaly because the philosophy behind discipline and punishment is no longer primitive. Indeed, the modern prison is increasingly being seen as a space for reforming — healing — the human spirit. Several experiments that are taking place in this respect in India and the world — the open prison is one example — are encouraging. But the doors can remain shut for long for those who retain the courage to speak truth to power. This constituency wages courageous, everyday — but little-known — battles to keep their minds free and fearless in the face of unprecedented intimidation and restrainment. The prison writings of several defiant citizens, young and old, of New India speak of this raging battle.