“It is our sovereign right to ensure Indian citizenship in our country, we will never compromise on it,” declared the Union home minister, Amit Shah, as he commenced the process of the implementation of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act. He also described, yet again, the opponents in the battle over citizenship as those who practise “appeasement and vote-bank politics”.

The timing of the CAA push, right on the eve of national elections, reflects its strategic importance for the Hindu nationalist regime. In its worldview, the renewed Citizenship Act marks a historical milestone in the journey of the nation. The move effectively forecloses Indian citizenship within the secure parameters of two primordial attachments. One, an emotional attachment to an eternal and exclusive Hindu civilisation. And second, an identity-centred affiliation with a global Hindu community (a ‘Hindu ummah’, if you will).

The CAA forms a key piece of the larger ideological project of restructuring the nation’s concept of time and space, thereby remoulding the basis of people’s evaluation of their subjective experience. Away from the ‘real’ empirical context of historical time and geographical space, people are being asked to contextualise their lived experiences within a mythic national journey as a significant part of the story of an eternal and organically whole Hindu people.

In his last Independence Day speech from the Red Fort, Narendra Modi had announced to the nation that it had entered Amrit Kaal and the sacrifices made and decisions taken now will resonate in the country for the next 1,000 years. The eerie echoes of Hitler’s signature ‘thousand-year Reich’ notwithstanding, Modi has reaffirmed the theme on several occasions, most notably while inaugurating the Ram temple in Ayodhya and framing the agenda for the next term of the NDA in Parliament.

In this article, let us keep away from the confounding thicket of legalistic arguments and stick to the practical significance of the political concepts that govern our lives. In this spirit, let us start with two simple questions. One, what is the practical value of democratic citizenship? Two, can this value of citizenship, like bread, turn stale?

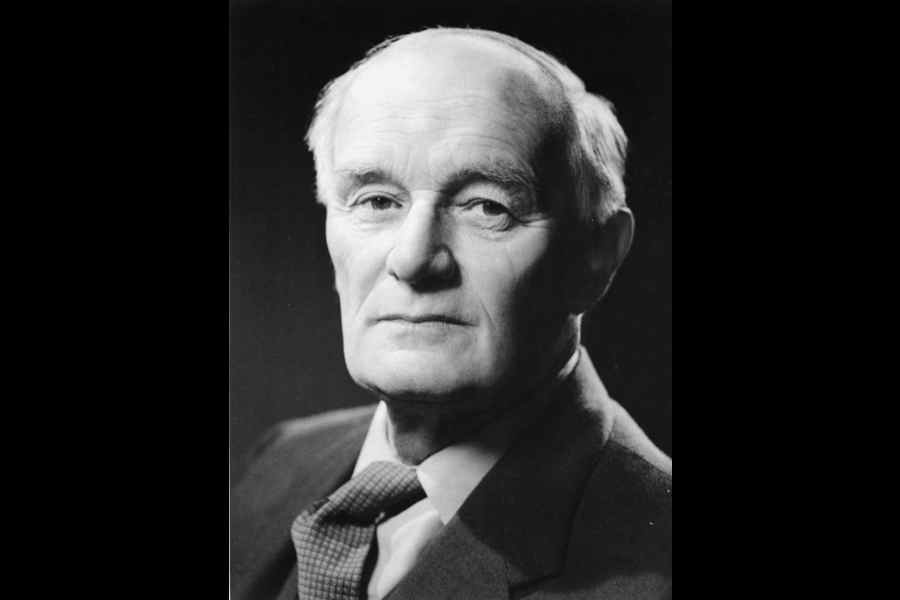

Drawing upon the history of Europe, the British sociologist, T.H. Marshall (picture), in his famed lecture, “Citizenship and Social Class” (1950), identified three levels of entitlements conferred by citizenship: civil, political and social. The civil element meant individual rights and freedoms (such as the freedom of speech and the right to hold property), while the political element meant the right to “participate in the exercise of political power” (such as the right to vote and form political parties).

These two aspects of citizenship are rather well-known. But any meaningful paradigm of citizenship also contains a third level of social citizenship, or a minimal guarantee of social security. Marshall defines social citizenship as encompassing a whole gamut of socio-economic entitlements — “from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage”.

The republican citizenship promised by India also contained prominently a collective resolve to guarantee to every citizen “the life (worthy) of a civilized being” (in Marshall’s words). For instance, the Directive Principles of State Policy comprise a series of articles that mandate future governments “to promote the welfare of the people by securing and protecting as effectively as it may a social order in which justice, social, economic and political, shall inform all the institutions of the national life.”

The central social promise of our republican citizenship has self-evidently turned stale, carrying little meaning for the vast majority of the population. In a 2019 report documenting India’s obscene level of socio-economic inequality, Oxfam presented several startling data points. Children from poor families in India are three times more likely to die before their first birthday than children from rich families. Forty-two per cent of India’s tribal children are underweight. A Dalit woman can expect to live almost 14.6 years less than a high-caste woman. The top 1% held around half of the country’s wealth. The combined federal and provincial budget for public health, sanitation and water supply was less than the wealth of Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man then.

These damning statistics move few souls among the governing elite or the upper middle classes for two broad reasons. The first is the gap in interests. This was explained half-a-century back by the Nobel laureate economist, Gunnar Myrdal, in Rich Lands and Poor (1958). The appearance of a “moral discord” between egalitarian promises of political citizenship and hideous socio-economic realities does not bother the elites because they are invested in the unequal paradigm. Myrdal argued that the elites instrumentalise any convenient economic theory to “serve opportunistic rationalization needs” to “live as comfortably as possible with the moral discord in their hearts” as long as they have an “economic theory that diverts attention from this moral discord”. The irony of India’s economic experience is the unmistakable continuity between the pre-1990s, State-led ‘socialist phase’ and the market-led ‘neoliberal phase’. Both phases were led by a similar cast of protagonists and favoured the same set of beneficiaries: a network of bureaucratic and political elites, allied big capitalists and the upper middle classes.

The second reason is the gap in experience. There exists a ‘wall of separation’ between the elite comfortably ensconced within the residential enclaves of India’s new gilded age and the India constituted by the majority of the precariat. The pandemic years saw the breaching of new records in SUV car sales alongside the relegation of nearly two-thirds of the population to dependence on the government for subsidised food grains. To borrow from Benjamin Disraeli, these constitute “two nations... between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts, and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones, or inhabitants of different planets.”

The promise of social citizenship has been meaningfully realised through a top-down process of beneficence handed down by the ruling elites in hardly any country. It is only through class-based political mobilisation that the underclass gains substantial rights. The capacity of citizens to press for “higher” citizenship rights, according to Marshall, depends on their level of historical consciousness. Briefly, citizens mobilise themselves for claiming their social rights only after having secured their political rights, which, in turn, they could press for after having gained their civil rights. Thus, Marshall defined the process of “becoming a citizen” in terms of a sequence: “It is possible, without doing violence to historical accuracy, to assign the formative period in the life of each to a different century—civil rights to the eighteenth, political to the nineteenth and social to the twentieth.”

In sum, the civil, political and social rights that people gained in Europe after a prolonged political struggle over two centuries was provided to Indian citizens by a ‘stroke of the pen’ through the Constitution. Yet, as Marshall reminded, citizenship rights mandated by laws are merely a promise or an aspiration that can only be realised in substance after a phase of popular class-based struggle.

It is true that India had belatedly embarked on certain tentative steps towards the fulfilment of social citizenship by the turn of the century. The UPA’s rights-based framework for social welfare did move the ball forward. Yet, even those small steps were undermined by the Congress-led regime’s crony-capitalist tilt and the deepening of welfare-commodification through cash payments to the poor.

The promise of inclusion within a secular republican citizenship having become stale, an alternative framework of ‘Hindu citizenship’ has ascended to take its place. The BJP has remoulded the ‘bread’ of citizenship in a heady ferment of nationalism and Hindutva. The Hindu nationalist project legitimises socio-economic inequality by depoliticising all distributional issues within the umbrella constituted by the Hindu people, embracing big capitalists and the poor alike. Alongside, it refocuses the material anxiety felt by the masses onto the shared figure of fear and hate represented by the ‘Muslim Other’.

One can find echoes of this in the Pakistan of the 1970s. In the latter half of his prime ministership, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto turned sharply towards ‘Project Islamisation’ and embarked on the persecution of the Ahmadiyya minority, after having demonstrably failed to accomplish the radical socio-economic transformation on which he had mobilised the masses. By the end of the decade, Bhutto would be overthrown by Zia-ul-Haq who fast-tracked the Islamisation project. Through all these transitions, the social order underneath would reflect the same ‘moral discord’ between the masses of impoverished poor and the ruling class of the feudal rich. The point of discontinuity only lay in the shift in the mode of legitimacy to accommodate the hideous and irresolvable discord.

Asim Ali is a political researcher and columnist