A busy plumber or a construction worker might be carrying a blob of yellow flowers on his t-shirt, unaware — and uninterested — that it is the sorry reproduction of an iconic painting of sunflowers by an artist who is himself an icon. Does anyone go into the incredible achievements of Leonardo da Vinci when they print the Mona Lisa on a mug? He is too remote to be an icon. And who looks twice at the Taj Mahal when it is printed on the lid of a box of chocolates — who remembers Shah Jahan or his artist-workers when they do? But Vincent van Gogh, who sold only one painting during his lifetime — not that of the sunflowers — and had to be treated in psychiatric hospitals, has emerged as an icon not just because of his greatness but more because he represents the romantic figure of the tormented, isolated, misunderstood artist. That he cut off his own ear in a fit of pique adds to his wild charm.

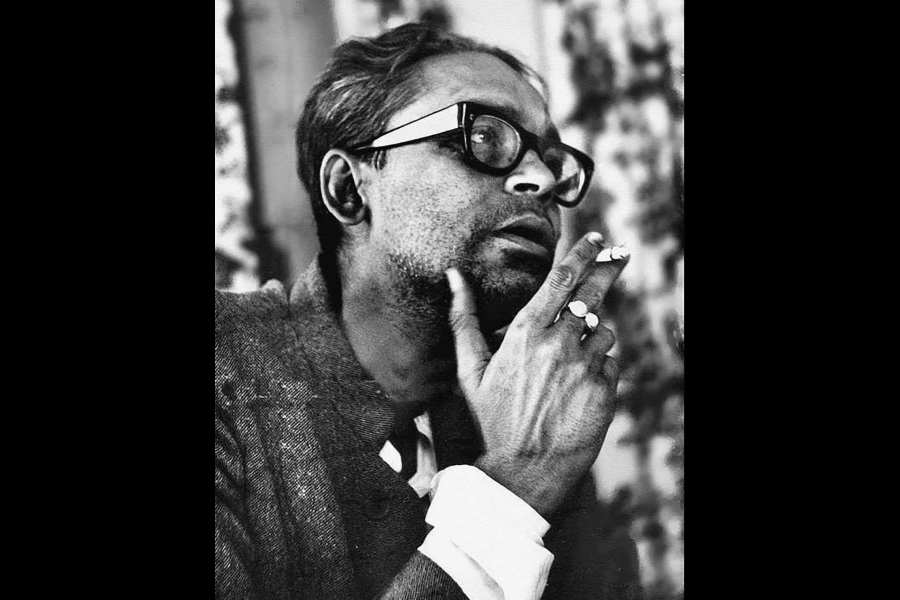

Society is fascinated by persons who ignore its mores, yet whose achievements the world acknowledges as great. Those who would never tolerate such persons in the family and would avoid them studiously in life proudly recite their names to claim them as part of their cultural heritage. Many of these figures have a kind of dramatic flair about their existence, a tragic power; often they exhibit a defiance of social expectations. It is ironic when they themselves are iconoclastic, rejecting unthinking deification, while their lives and works tear apart society’s hypocrisies or expose the sources and nature of suffering. Ritwik Ghatak, for example, who is about to turn 100 in 2025, can become an icon claimed by all, whether or not they have seen his films. While iconisation is a tribute, it is also blinding. It simplifies the multifariousness of the icon’s achievement and pulls greatness into everyday grasp. A station named after Ghatak, say, or after Subhas Chandra Bose, becomes part of daily routine. It spares the task of thinking, and the deep discomfort that may come from engaging with their achievements. Deification is a comfortable short-cut: claim without responsibility.

Making icons is thus double-edged, but it is dangerous when the icon is an active politician. A certain kind of politics invites iconisation, precisely because an adored leader’s acts are then obscured by worship, making thought irrelevant. Iconisation takes on the qualities of a cult, evoking in its followers those attributes that the leader can put to his own use. History, both past and contemporary, shows how devastating the effects of this can be, which is why the process must be disrupted when there is still time. With artists, the effects are different. Ghatak, and others like him, may laugh at their own presence at street corners or on mugs — India, after all, cannot resist deifying its heroes — but they would deplore the fact that their message still does not reach the people with whom they wanted to communicate.