By 2025, if not earlier, I expect five major titles dominating the world of books. Coming under the category of fiction, they will all be products of the pandemic and its biggest fallout — fear. Let me visualize them.

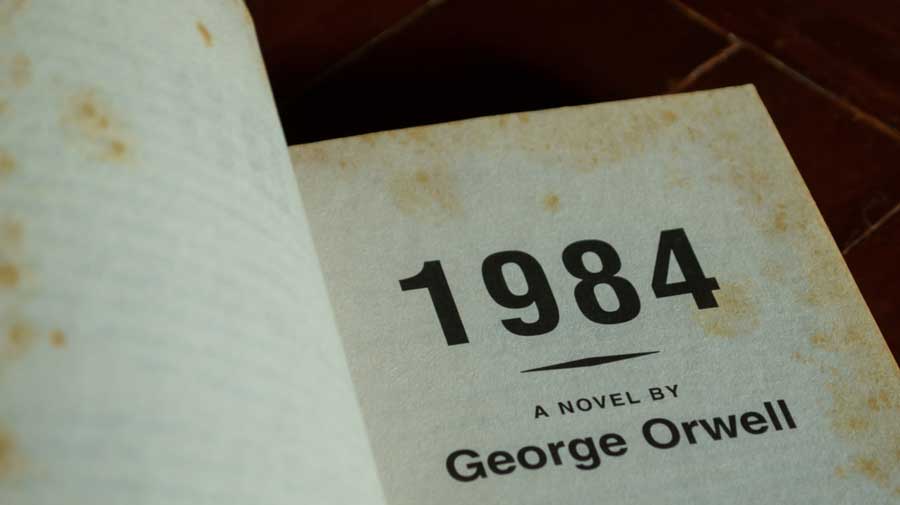

The first, titled 2025, is a political masterpiece of the calibre of Orwell’s 1984. Written by an Australian of Chinese descent, it is about a tyrant from the Far East who establishes a four-nation Axis with one country in North Africa, one in Europe, and one in South America. On Christmas eve, 2025, the Axis Powers launch a global assault on democracies through a cyber invasion that completely cripples the digital handles the world knows today, causing its banking portals to collapse, its security sites to crumble, its governance to come to a standstill. Airlines grind down, railways hiss to a halt, internet activity stops, mobile telephony ceases to operate in country after country. The Axis offers a restoration of ‘order’ under a new cyber system, which it controls exclusively, rigidly. One signal comes through: COMPLY WITH NEW ORDER. Twenty-four hours are given for compliance, else bombs will shower disease. Stunned, the United States of America moves to put a firewall in place to protect its digital systems. The president of the US — a gutsy woman — seeks to call the heads of the world’s democracies but can reach only a few. In the place of the voice of those she cannot get through to, she hears a short laugh with the following voice message: ‘Smart, eh? Too late.’ She does get through to New Delhi. ‘We have to join up,’ she is told by her equally strong counterpart, ‘but how?’

The second work of fiction, perhaps titled Zero Hour, is a science thriller but also high literature of the style of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Written by a Brazilian, it is about a cabal of five theoretical physicists who have retired from their countries’ defence laboratories, but are led by an electronic wizard who has moved from physics to digital technology out of what he calls ‘plain mad love’ of that expertise. They have known each other from conferences and have exchanged personal contact lines in addition to their official ones. They have an encrypted code that is so protected within its folds as to be impermeable, unstoppable, incorruptible and — unintelligible to all but the five. It has been refined as to be un-hackable, un-destroyable by man or virus or a combination of the two. The five have a macabre sense of humour. They want to paralyze the world, not to control it but to chastise it. They loathe humanity. For its cunning destructiveness, its bizarre hatred of life, its perverse lust for murder. They believe, with no evidence but just a hunch, that the virus that gripped the world in 2020 was a man-made affair, like the atom bomb. They loathe humanity for doing that. They choose countries by the first letters of their names and, starting on July 16, 2025, immobilize their electronics one by one. Afghanistan cannot figure out what is happening to it. It cannot connect to what happens next to Albania. And then Algeria... Why on July 16? They have a God — J.R. Oppenheimer, leader of the Trinity test in New Mexico where the first atomic bomb was test-detonated on that date. They have not read the Bhagavad Gita but know Oppenheimer’s quote from it: “I am become Death.” They see themselves as that ‘I’. And they want to enact “I am become Death.” They have decided to die with the dying. Die laughing. They are brave. They are mad. And they know their way to what they want to achieve.

The third best-selling work of the imagination is titled The Return of the Species. It is the audacious work of a zoologist, a young Ethiopian, who knows Darwin’s work as closely as a palmist knows the lines on his own hand’s inside. She has followed the natural history of Planet Earth with the zeal of a lioness beholding prey for her hungry young. She has been thrilled by the few weeks, soon after ‘Wuhan’, when the human world went into lockdown and the animal world came out into unlock. She writes with unconcealed relish of an ‘ecologically ideal’ scene when the virus spreads and the lockdown cannot ever be lifted, of hippopotami walking into city centres, nilgais roaming in the Taj Mahal’s now wild lawn, snakes sliding over Cecil Rhodes’s statue atop Table Mountain, kangaroo strolling in the La Trobe campus, of the air over Lahore and Tokyo becoming so clean, so pure, that the spangled stars overhead can be seen piercingly bright. And in an Animal Farm replay, she has a she-elephant wandering into a zoo and getting so enraged seeing other elephants inside it that leading a charge into the zoo she sets the captives free.

The fourth nugget of fiction is called The Waft. Written originally in Bangla, it has been translated into English by the writer’s divorced wife, an Irishwoman living by herself in Dublin. The author is a forty-five-year-old flautist, trained in Santiniketan’s Sangit Bhavana, but unemployed and un-employable. He is a genius with the flute, a waif without it. He has been teaching his music to students in Calcutta. But they are few and very often unable to pay him anything more than his bus fare. Ever since the pandemic, he is unable to go to them. His meagre earning has stopped. He manages to come to his village in Khatra, the most beautiful part of West Bengal’s stunning district of Bankura. Sitting day after day in his childless aunt’s home, fed by her, he stares at the mind-boggling sky in all its hues, plays on his flute and composes lyrics to ragas he loves. When she calls him Kalidas, he simply smiles. His lyrics are about the seasons. He plays, writes, plays, writes. Playing the Megha Malhar, gliding from komal nishad to pancham, he writes, “The cloud... wafts... with the panic of a veil... flying after the girl who has dropped it, running...” He writes about all the six seasons and, one evening, after playing Hamir centred around shuddha dhaivat with a downward glide from nishad, writes about a seventh season... Akaala... the ‘unseasonal...’ This Akaala can come now any time anywhere... unwanted but undeflectable... wafting...

The fifth is a slim, 50-page work, which its publisher has titled The End. It has been written — in just one evening — by a half-Myanmarese, half-Israeli virologist in Boston who has been working on the vaccine. The vaccine. Its last sentence is incomplete. The writer knows all that there is to know about the virus, the vaccine. He knows how vital it is, how fragile. He knows the world’s need for it, its hopes for it. He has taken it from stage to stage with his team. They are all skilled, sincere, just as he is. But he is also — as only Louise, his fiancée, knows — given to depression. On the evening he is to write this, just as he is leaving the lab, getting out of his ‘space-suit’ as he calls it, a colleague says, “It may not really work... You know... the chances are... fifty-fifty... It may cover only fifty per cent of the world... And that also for just fifty per cent of the risk...” Back in his flat, he writes the fifty pages about his fear of the vaccine’s failure... Louise calls later that night as she does each night. There is no answer. She goes across, nervous. She has spare keys to the flat. The laptop is open, lit. He is slumped over it. She takes the manuscript some days later to its publisher. It appears the day the vaccine is placed in the market.