The scale and intensity of India’s civilian protests against the new citizenship law and the proposed national register of citizens prove that something fundamental is at stake — the future of a pluralist and tolerant nation. India’s survival as a democratic nation state, despite its variegated diversity, is regarded as one of the most miraculous eventualities of modern political history. In a society too diverse to be identified by any particular ossified identity, its elaborately codified Constitution serves as a linchpin for the survival of the idea as well as the practice associated with India’s nationhood.

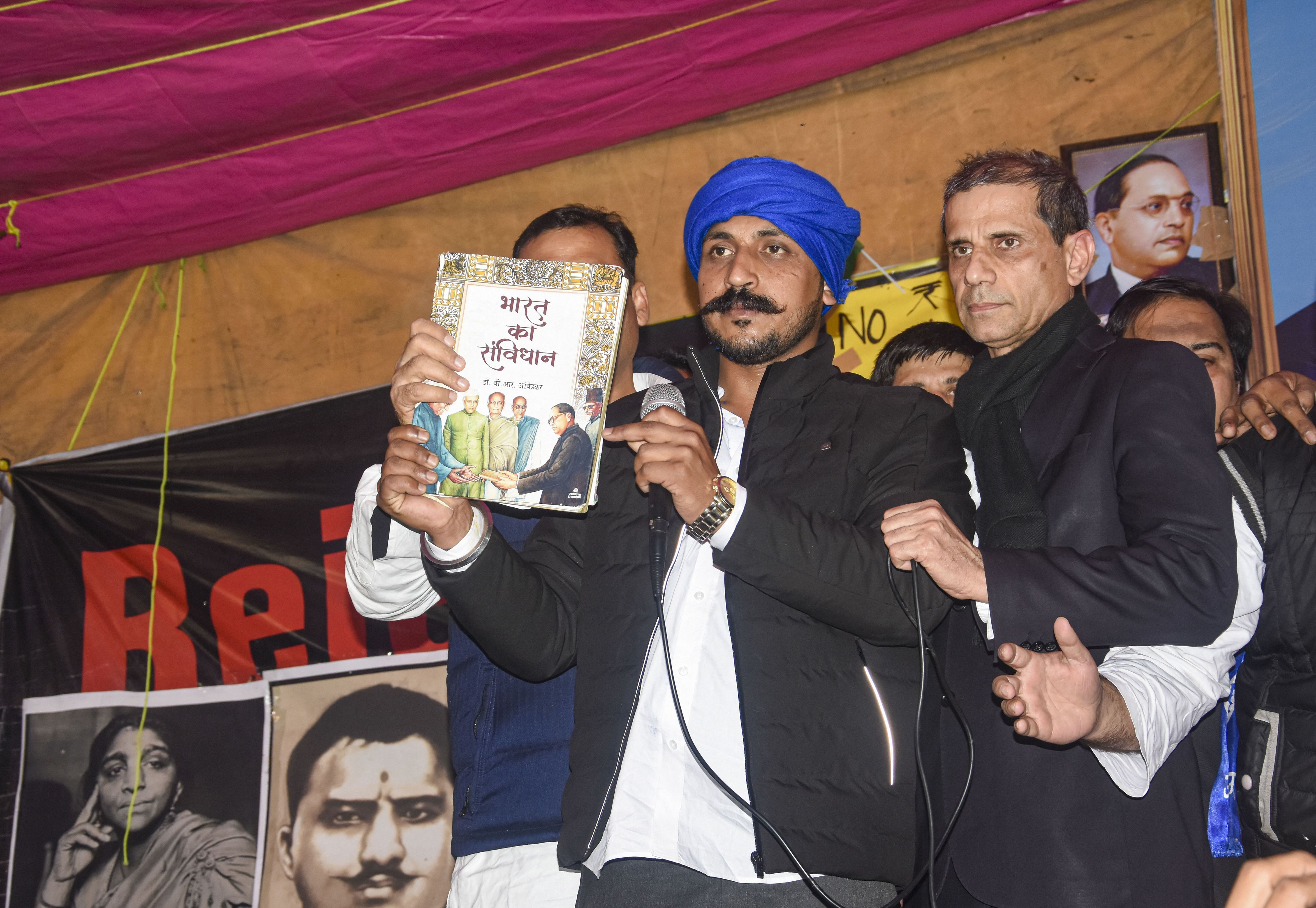

India’s new-age civilian resistance has evoked the Constitution as a central component in voicing dissent against the present dispensation. Symbols of ‘constitutional patriotism’, such as the national flag, the national anthem and the Preamble, have been invoked in these protests. The imagery seeks to reinforce the original idea of India that the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the NRC threaten to squander. In dissenting against a government that is massively popular, electorally powerful and institutionally repressive, the civilian resistance has invoked the Constitution for both legal and normative purposes. A Constitution, which was supposed to be merely a template for governance, is thus being understood and invoked very differently by different constituents of the protesting people.

The protests are not monolithic; there is vociferous resistance from three constituencies. It all began with the conflagration triggered against the CAA in the northeastern states, especially Assam. The opposition emanates from the fear that the proposed legislation would render decades of tumultuous struggle against the illegal immigration futile. There is also resistance from the Muslim community, which finds itself vulnerable and blatantly discriminated against by the double onslaught of CAA-NRC. Finally, there is the conscientious civil society, especially university students, braving the excesses of the State clampdown to oppose the government’s move which they feel is antithetical to a pluralist, democratic India. For the protesters from the Northeast and the Muslim community, the struggle is existential; for students and civil society, the protests are ideological.

These constituencies have evoked three different aspects of the Constitution in order to legitimize their protests. First, is the recourse to the traditional conception of perceiving the Constitution as a book of laws. This is essential to check an electoral juggernaut like the Bharatiya Janata Party, which has massive control over the legislative bodies and may not be averse to the risks of changing laws and inflicting institutional damage. Second, the CAA-NRC is a project of homogeneity that the Hindutva brigade has aimed at. A moral reading of the Constitution counters this goal by putting forward the idea of a pluralistic India. Heterogeneity is as much a necessity as it is a desirable goal. Finally, the foundational idea of India inspired by the principles and visions of M.K. Gandhi and B.R. Ambedkar has been drawn upon to support the cause of a secular and egalitarian society.

In a diverse polity like India, discriminatory policies based on identity and citizenship are evoking diverse forms of resistance. However, what binds these distinct constituencies and the distinctive causes of protest is the shared idea and practice of the Constitution. But again, true to India’s heterogeneity, the language of invoking and the perceptions of the Constitution are not similar. The fate of a plural democratic India rests upon this reinforcement of ‘constitutional sanctity’ in the face of repeated attempts to instil majoritarianism.