This year marks the 80th anniversary of the apocalyptic Bengal Famine of 1943. Researchers are divided on how many people starved to death in that calamity — figures vary between three and five million. As everyone knows by now, the reason for the deaths lay elsewhere. The then racist British prime minister masterminded the diversion of food, which was in abundant supply following a particularly good harvest that year, from the starving Indians to British soldiers fighting the War.

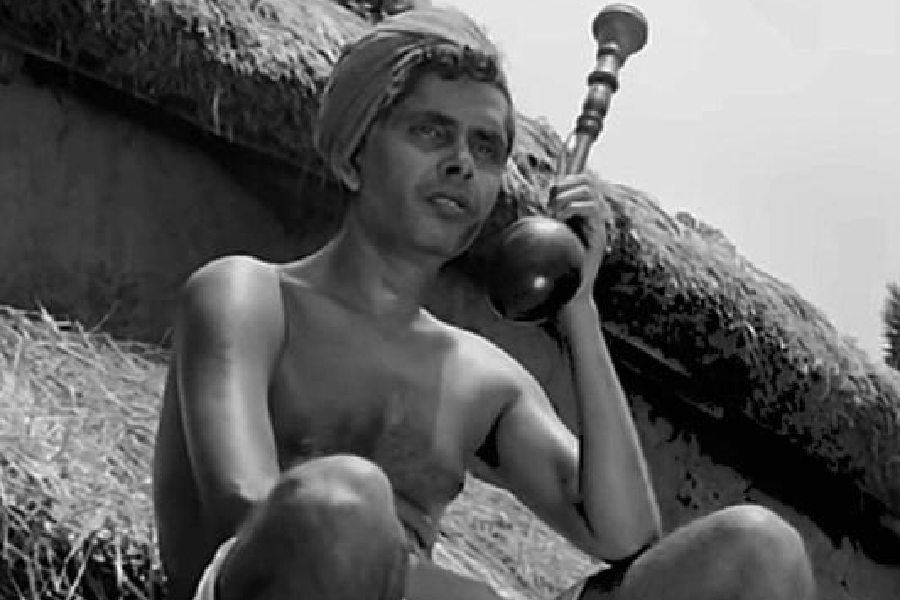

Coincidentally, the birth centenary of Mrinal Sen, known for his humanist cinematic depiction of mass hunger, has fallen at a time when there are fresh deliberations on that horrific event of 1943. Sen’s ‘famine films’, beginning with Baishey Shraban, refused to cater to the sensationalism or the sentimentalism demanded by market-driven conventional cinema.

Strikingly, even cinephiles have sometimes been known not to notice that Sen could appear in many avatars when it came to depicting the damage wrought by hunger on the individual and the collective psyche. In Kolkata Ekattar or, say, Akaler Sandhaney, the maverick grabbed public attention as a pamphleteer or polemicist; in Baishey Shraban, he was, arguably, at his creative best, as he quietly went about showing the death of a marriage in rural Bengal with the gradually deepening crisis of the famine serving as the film’s backdrop. With rare mastery, Sen fused the slowly widening fissures in the doomed marriage with the bigger picture of people deserting the village in search of food elsewhere.

Sen was once asked by a film-society organiser why he kept repeating the themes of exploitation, poverty, famine, hunger and such other calamities in his films. The director’s reply was clear and forthright: “I strongly feel that I, as a social being, am committed to my own times… [S]ince poverty, famine and social injustice are dominant facts of my own times, my business as a filmmaker is to understand them.” He might as well have added that poverty and hunger are ageless and universal phenomena, especially evident in lands ravaged for centuries by colonial powers and native elites; hence, artists of conscience, wherever they are, would never cease to comment on them as they thought fit.

And what could be more contemporary, relevant and pressing than hunger and the differing attitudes it evokes in different sections of society? In living memory, perhaps no calamity brought out the best and the worst in men and women the world over than the Covid pandemic — more ‘worst’ than ‘best’. It will be a long time before the indifference of the upper and middle classes towards the plight of the poor is forgotten. One can well imagine the text or the texture of the kind of films that Sen would have made had he been living and working during the pandemic.

If Sen had stopped making films after Baishey Shraban, he would still be considered a distinguished director, such was the quiet passion and beauty of construction that went into his chronicling and critiquing of the crisis of 1943. Sen himself appears to have been confident of what he had created. Speaking in 2003, he said: “Amongst my own films, I like Baishey Shraban the best because it has a conscious contemporary sensibility to it, which… seems relevant even today”. Was there ever a time when the Horseman of Famine did not trample underfoot the poor and the powerless of the world?