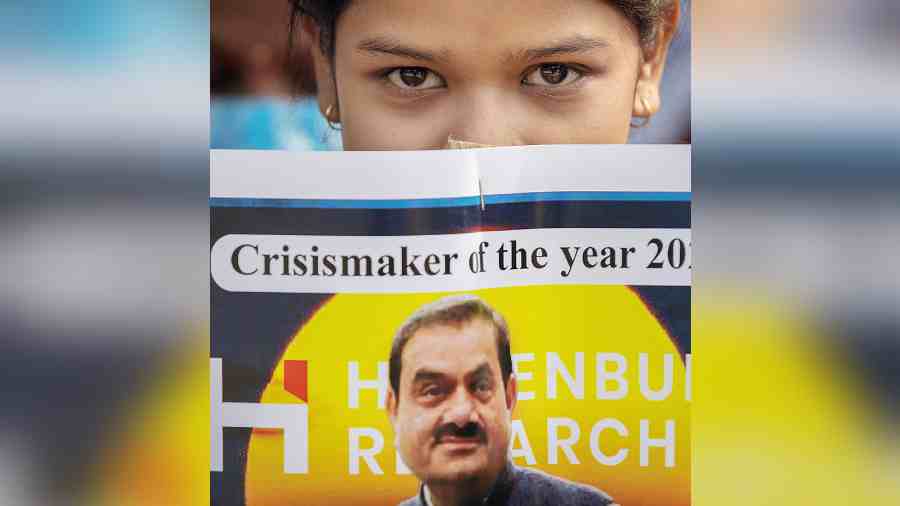

On hearing of the Adani exposé by Hindenburg Research, I was, frankly, not surprised. The Adani Group’s meteoric rise was always too fast and furious to be true. There was something surreal about it. It was like a company’s profits jumping suddenly by four-digit percentage points, or a fund promising 200% returns on investments. Sometimes, in such cases, the business entity concerned is caught embarrassingly exposed, like a chit fund or a Ponzi scheme. Also, quite expectedly, as soon as the long list of allegations became public knowledge, two responses emerged as reactions. The first focused on it as an attack of an evil Western world on India out of sheer jealousy. Nothing could touch India, and the nation (equated with the Adani business empire) would continue to march on. The second response was that it was a case of crony capitalism and an example of the cosy connections between big business and the top political leadership. This self-seeking nexus would ruin India’s reputation and hurt its economy. Markets would tumble and crash. If indeed such a thing occurs, the interesting point to note would be whether the government bails the businessman out by giving him a clean chit of health.

If one leaves these extreme, rather predictable, responses aside, the first thing that comes to mind is this: how does one separate the wheat from the chaff? How to find the truth-claims on either side? The only way to get it straight is to examine the allegations and the rebuttals in detail. That is the only logical way. However, investigations take time. Moreover, in an overwhelming majority of cases, hardly any concrete, publicly available information emerges after years of probing. They become tales of conspiracy that abound in every society. What happened in Bofors? What happened in the Rafale deal? Or Pegasus?

So if one cannot be comfortable with the extreme responses, and one also cannot expect the truthclaims to be tested and revealed, what could one possibly do? One way would be to deconstruct the system out of which the episode emerged — the story of Gautam Adani’s phenomenal growth, his close links with political leaders at the highest level, the way in which the financial assets and credit markets might have been duped and, finally, how regulators missed out or looked the other way.

The textbook model of a market claims that no single player, whether buyer or seller, can influence outcomes in terms of prices and quantities transacted. It also claims that the participants together could not have done any better than the outcome thrown up by an unfettered market. This is referred to as economic efficiency. Economists know that in reality no market actually works that well. The ability of sellers to influence prices and volumes is omnipresent. Indeed, there is no general theory of economic markets except the claim that prices and quantities emerge through an interaction of exchanging buyers and sellers. The core point is to maximise advantage, if possible even at the expense of others. Since manipulation is impossible in an ideally competitive market, there must be an autonomous correction mechanism that equates supply to demand. Hence, some commentators have referred to the Adani meltdown as a market correction. If it is, it is certainly not through an autonomous channel; it was triggered by an investigative study of the firms.

The specific allegations against the Adani Group have been around the use of off-shore shell companies located in tax havens to transfer, through fraudulent accounting, money and stocks to these shell companies; using these resources to manipulate and drive up the Adani Group’s share prices, and then using these inflated-value shares as collaterals to obtain large loans from financial institutions. If the Adani Group did indulge in such practices, as alleged, then it did not do something spectacularly unusual. If Hindenburg, or any other research firm worth its salt, took up such investigative projects, a very large number of big, medium and small companies across the world would be seen to be doing exactly these, albeit in different doses and degrees.

The first line of checks against such practices getting out of control is the audit function in a listed entity. Clearly, in the Adani case, the auditors must have behaved opportunistically in furthering their own economic gains or have been astoundingly stupid. The memories of Arthur Andersen and Enron come to mind.

The second line of defence is institutional regulators. Market regulators often turn out to be myopic in their actions and in their ability to scrutinise disclosures. It may have been a similar case in this instance.

A third line of defence is whistleblowers. Why does not an accounts executive, who knows the kind of gaming going on, blow the whistle? The strength and the scale of the power of big business against a small whistleblower is not comparable. A whistleblower can be bought off, or even made to disappear in the blink of an eye.

The fourth line of defence comprises the moral scruples of the people in the business entity in charge of corporate governance. Manipulative executives often make sure that the board gets an incomplete view of the total picture. In other cases, the board might choose to shut its eyes in the hope that the near-term future would be rosier and things would be forgotten in the long run. This is where corporate ethics comes into play. In the boardroom, there are regulatory or legal constraints. Violating them would be tantamount to an illegal action. Such decisions are unacceptable. There are other, more nuanced, situations where there are no clear laws, nor any clear right or wrong. This is where individual morality is usually rationalised by the claim that enhancing individual advantage is necessary for the greater good of society. If the captain of industry is taking the nation’s economy forward, what is all the fuss about giving a little nudge to share valuations? The megalomania is real: that is why Mr Adani thinks an attack on his business is an attack on India.

Finally, the one important reason for the attention Mr Adani has drawn, apart from the sheer size of his empire, is his wellknown, long-time proximity to the highest political leadership. However, this too is nothing new. Capitalism is essentially based on cronyism — without nudges from politicians, no tycoon could arrive or survive at the top. The State has always been the sales force of big business. There is a symbiotic relationship: business requires the support and blessings of the government, while politicians need financial contributions from business to win elections. Big business and big politics have always been very comfortable bedfellows.

What we witness in the Adani story is a negative print of the raw cut of capitalism. When washed well and hung-dried, we get to see the positive print of modernity: India on the march in a global market. It is not a question of right or wrong: it is one of who has more power. I expect Mr Adani to win. Capitalism unchained is about keeping the cookie jar perpetually full. It is a familiar story, after all.

Anup Sinha is former Professor of Economics, IIM Calcutta