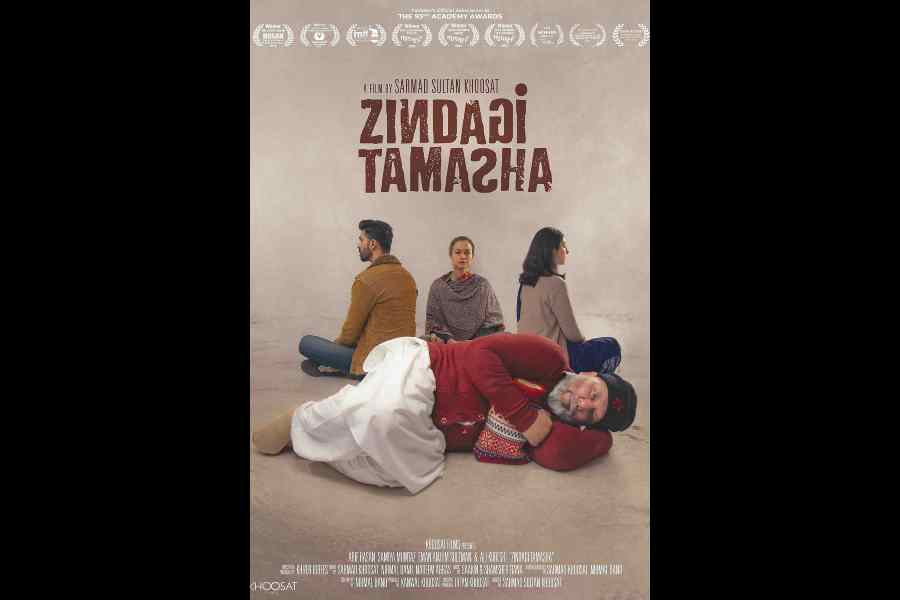

Screened for the first time during the pandemic, Sarmad Khoosat’s film, Zindagi Tamasha, won many accolades at various film festivals in Pakistan and globally. The one thing it could not win was the approval of Pakistan’s censor board and was thus not allowed a theatrical release. Quite a few fundamentalist outfits campaigned for banning the film, with the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan, a group that came into existence to oppose the dilution or the altering of Pakistan’s strict blasphemy laws, being especially invested in the campaign.

Zindagi Tamasha portrays the struggle of a ‘Naat Khwaan’ (one who recites poems in honour of the Prophet) who loses his religious credibility when a video of him performing a ‘feminine dance’ at a relative’s wedding goes viral. The protagonist is then socially boycotted by colleagues, neighbours, friends, and even family members. When the protagonist attends a recitation programme in which he had been an honoured guest for many years, he realises that he has been banned from joining the event. When he refuses to leave, a local priest threatens to accuse him of ‘raising the slogan’ — suggesting a deliberate misuse of blasphemy allegations. It is at this point that the protagonist decides to back down and leaves the premises fearing for his life.

Blasphemy allegations, as Zindagi Tamasha shows, are easy to make in Pakistan. In May, a senior Christian citizen in the Sargodha area of Punjab was attacked by a mob and his factory burnt down because of allegations of blasphemy. A case was registered against several suspects. But the police also lodged a case against the victim of the mob attack for blasphemy; the allegations had been made by a local TLP member. In June, a Punjabi tourist was lynched and publicly set ablaze in the Swat district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Initial reports suggest that the tourists had got into an argument with a local shopkeeper after which the locals accused him of blasphemy.

Many allegations of blasphemy have led to mob violence. Last year, a blasphemy accusation in Jaranwala led to a full-scale riot against the Christian community. However, the police investigation revealed that the incident was a case of personal enmity. When contract killers hired by one person to kill another failed to do the job, the former decided to accuse the latter of desecrating the Quran by planting false evidence outside his rival’s house. Similar investigations into other cases have also found that incidents of blasphemy are often forged to target marginalised communities or for the purpose of settling personal scores and property disputes. In one of its reports, the Lahore-based National Commission for Justice and Peace claimed that in over 100 cases in which defendants in blasphemy trials were found to be innocent, the accusers had been, in the court’s view, motivated by personal grudges or had hoped for financial gain.

In Pakistan, acts of alleged defilement of the Quran are punishable by a term that can extend up to life imprisonment. This penal provision was introduced in 1982, one of many additions to the blasphemy laws between 1980 and 1984 introduced by Zia-ul-Haq’s military regime. The controversial blasphemy law has been used by successive regimes to consolidate the support of the Sunni majority and disenfranchise religious minorities like Christians, Ahmadi Muslims, and Shia Muslims.

Religious sentiments may be easy to ignite but they are almost impossible to control. Now even members of the Sunni majority are falling prey to such violence. What is of particular concern is that groups like the TLP seek to keep themselves politically relevant by claiming to protect and perpetuate Pakistan’s already strict blasphemy laws. This raises serious questions about the credibility of the accusations made by its members. Wherever there is an abundant supply of religious hatred, it is often politically expedient for actors to fan the flames.