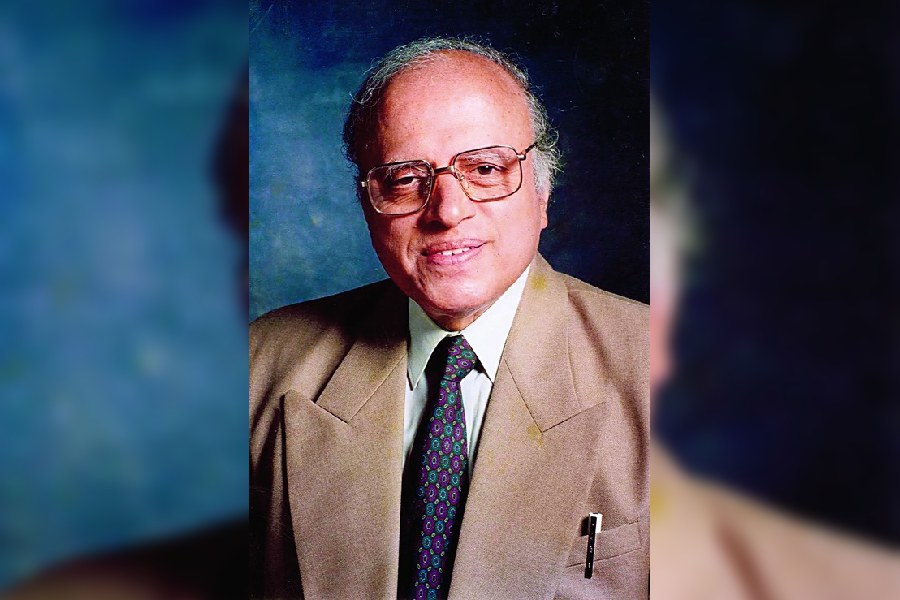

M.S. Swaminathan, who passed away recently, is best known as the pioneer who ushered in the Green Revolution that made India a food-secure nation. But it is perhaps Swaminathan’s later work that holds greater significance for India and a world battling climate change. Sensing that the long-term detriments of the Green Revolution — the loss of soil fertility, threats to indigenous varieties of food grains and so on — outweighed its short-term gains, Swaminathan had called for an “Evergreen Revolution”, which would enhance productivity in perpetuity without perpetrating ecological harm. This clarion call underscored the need for increased public investment in irrigation, an area of concern in light of a recent World Bank report that found India to be the most water-stressed country globally. Falling investments in irrigation, a misguided focus on canal irrigation and apathy towards replenishing groundwater sources have made Indian farmers especially vulnerable to the vagaries of the weather. Swaminathan had also forewarned against the adoption of populist measures such as the provision of free or subsidised electricity to farmers. But most Indian political parties continue to dangle this electoral carrot — the Aam Aadmi Party came to power in Punjab on the back of such a pledge — notwithstanding the deleterious impact of such interventions on agrarian resources.

Yet another fallout of the Green Revolution has been the over-dependence on staples like rice, wheat and maize. Swaminathan anticipated this and prescribed the revival of traditional crops like jowar, bajra and pulses as well as their inclusion in the public distribution system: the Centre’s policy push for millets is, effectively, a leaf out of his book. His demand for the redefinition — problematisation — of food security into chronic hunger (caused by inadequate purchasing power), hidden hunger (the result of the deficiency of micronutrients in the diet) and transient hunger (the consequence of disasters like drought, floods, cyclones) was, once again, quite original. Any hunger-reduction strategy, whether national or global, must address all these dimensions. Indian agriculture is precariously placed with the onset of the Anthropocene. Policymakers and indifferent politicians must fall back on Swaminathan’s legacy to chart the troubled waters.