My Kindle app is a grid of coloured icons the size of postage stamps. Each icon is a science fiction novel. Over the years, I’ve read so much SF that literary fiction sometimes seems like a niche genre. Such literary novels as I have read have been dead-tree books as have been the histories, biographies and nonfiction that fall to an academic’s lot. The worthiness of literary fiction and scholarly work seems to demand the heft of a conventionally made book. The high-wire excitement of science fiction, on the other hand, unburdened by realist ballast and buoyed up by a speculative lightness of being, is a good fit for the weightlessness of digital reading.

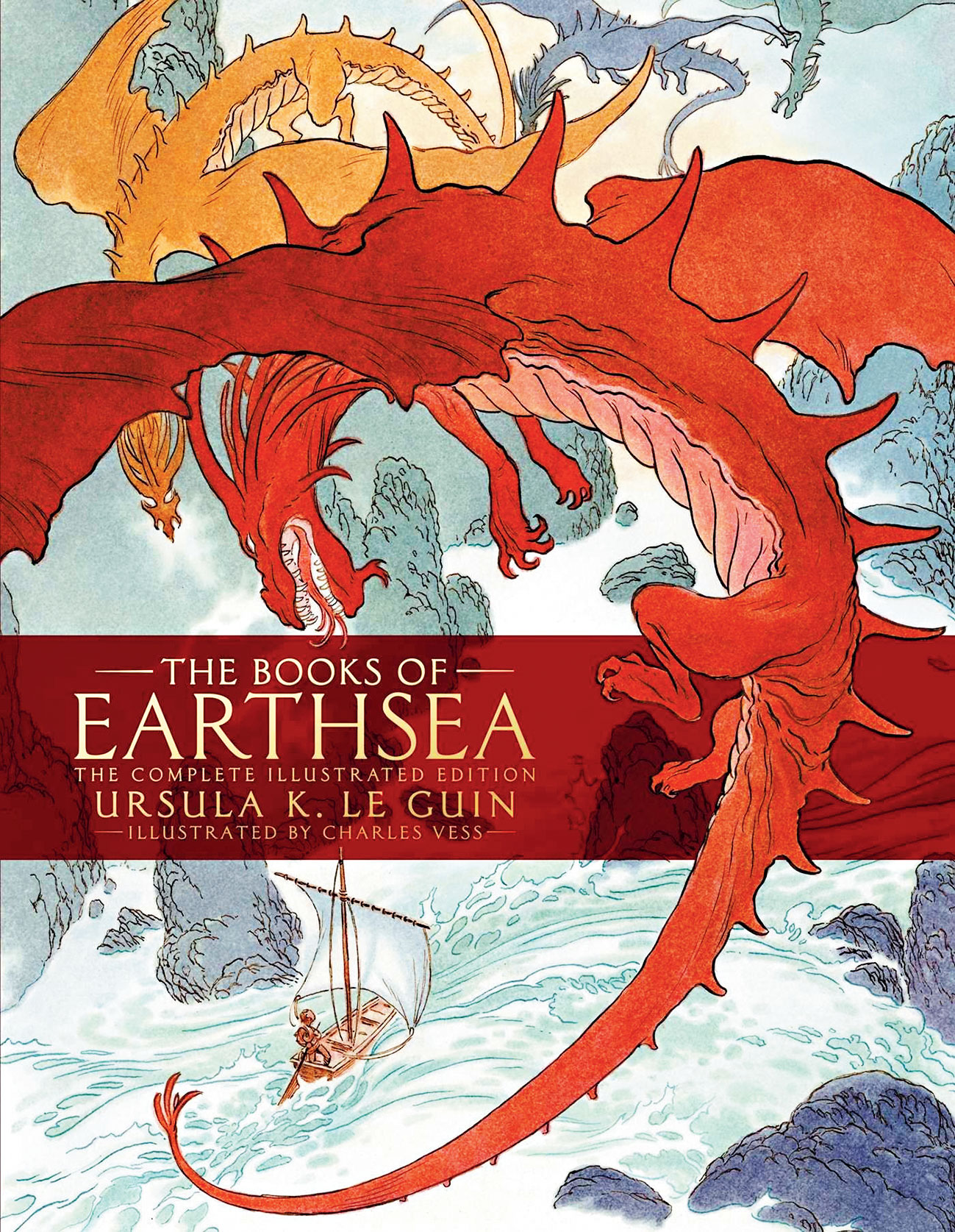

Binge reading was always a thing, long before Netflix made binge-watching possible, but being able to download the novel you want to read in seconds, wherever you are, makes gorging on the writer you currently love possible in a way that it wasn’t before. After years of going on about Ursula K. Le Guin on the strength of having read her masterpiece, The Left Hand of Darkness, I raced through her Earthsea Chronicles in a week. If she’d done the decent thing and written a dozen more instalments of that saga, I could have put off returning to the badly coded simulation called real life for another fortnight.

Le Guin, who died recently, would have been delighted by the resurgence of women in the sometimes laddish world of science fiction. N.K. Jemisin, an African-American novelist, set this world alight by winning the Hugo, the biggest annual prize for science fiction and fantasy, three years in a row for her Broken Earth Trilogy. Jemisin’s world-building in the first novel of the trilogy, The Fifth Season, is godlike. She invents a post-apocalyptic earth racked by Seasons, long epochs of geological chaos during which stability is maintained by gifted mutants called orogenes who can reach into the stirring depths of the earth and still its quakings. It is bizarrely good; that moment when you discover that the three protagonists of the first volume are the same person is one of the genre’s great reveals. It is also a fine illustration of how first-rate writing produces cultish followings made up of initiated readers who begin to think of themselves as adepts.

Just before the Jemisin trilogy took the world by storm, another woman, Ann Leckie, won every SF prize in sight for the first volume of her feminist space opera trilogy, Imperial Radch. Ancillary Justice’s protagonist, Breq, is the strangest main character in fiction, the AI of a defunct starship marooned in the body of its last living soldier. Just to make her stranger, Breq’s is an ungendered body: everyone in Radchai society uses female pronouns. I like to think that this is Leckie’s homage to Le Guin, the writer who first invented in The Left Hand of Darkness a human society where every individual was sexed in the same way and where either partner in a relationship could choose to transition into child-bearing. To watch Le Guin tease out the implications of this organizing idea in her novel was to realize that science fiction was the natural vessel for the radical, utopian imagination.

The excellence of Jemisin and Leckie doesn’t mean that contemporary SF is consistently good. It also produces turkeys. Take, for example, the 2019 Hugo winner for best novel, The Calculating Stars, by Mary Robinette Kowal. In an alternative earth where Dewey has won the US presidential election after the Second World War, a meteorite strike on Washington DC triggers global warming and a race against time to find a new home for humanity. Instead of going someplace strange with this set up, Kowal gives us, in numbing detail, a second-wave feminist account of Fifties male prejudice against ‘lady astronauts’. It’s like Mad Men without the art direction.

Even Jemisin and Leckie fade perceptibly through their trilogies. SF produces lots of trilogies and even longer multi-volume sagas. It is completely understandable that having created a densely imagined world, the author wants to inhabit it properly and use it more than once. But it does seem to be an iron law of trilogy writing that the first volume where the world is laid out is the tour de force and it’s downhill from there on. By the time Jemisin gets to the end of The Stone Sky, the concluding volume of her trilogy, the itinerary of her characters as they move through the earth’s mantle and between the earth and the moon becomes so arbitrary and implausible that the willing suspension of disbelief that good SF readers offer up to their favourite writers begins to fail.

The Remembrance of Earth’s Past, arguably the most ambitious trilogy in contemporary fiction, suffers from the same problem. Liu Cixin invents an extraordinary world that begins in what can only be described as Mao-ish China and then expands into a nightmarish universe where any evidence of planetary intelligence is inevitably punished by annihilation. This riveting confection, equal-parts high concept fiction and conspiracy theory, ends with an interminable description of the literal flattening of the universe into two dimensions.

Likewise Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy has an outstanding opening with Northern Lights. His alternative Oxford controlled by a European theocracy where science is experimental theology, where photographs are photograms and human beings have visible animal souls called daemons, is a magnificent invention. By the time he gets to the concluding volume, The Amber Spyglass, Pullman’s inner atheist gets the better of the storyteller in him and the trilogy ends with a baffling anathema directed at our Father and his angels which makes you nostalgic for the simple pleasures of Lyra’s world. Bringing a trilogy home is clearly something of a three body problem.

Still, even the less-than-brilliant volumes of these trilogies offer greater pleasures than most mainstream stand-alone novels paralysed as they are by the stasis of literary seriousness. Edgar Allan Poe and H.G. Wells are worth a round dozen of Henry James or D.H. Lawrence. James and Lawrence are historically interesting for what their fictions tell us about literary fashion at the time. Kingsley Amis once wrote of James’s experiments with tedium that ‘he chewed on more than he bit off’. That’s a charge no one can level against SF writers no matter how off their game they might be in certain of their novels. (I’d exclude Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman from this defence; they have to be the two most inflated reputations in genre fiction.)

Any extended reading of science fiction prompts a revaluation of literary fiction. After reading Frankenstein, it is obvious to the meanest intelligence that Shelley’s husband was a minor poet with a striking turn of phrase, and she was the literary giant who literally transformed the human imagination with her writing. Besides a writer really can’t call himself Percy Bysshe and expect to be taken seriously unless he’s auditioning for a part in a Drones Club scene written by Pelham Grenville.

And then, of course, there is that great dystopic serial on Netflix that has done for post-independence India what The Man in the High Castle did for post-war America. Godse ki Duniya has transfixed Indians for five riveting seasons by drawing them into the counter-factual history of an alternative republic run by Godse’s gurus and admirers. It overdoes, like much else in contemporary television fiction, the blood and gore and random killing, but it is so immersive and true to life that it is just as well that we can turn it off. Some things are best left to the imagination.