The exchange of words of Pakistan’s foreign minister, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, with his Indian counterpart at the United Nations last month may well have embarrassed even the trenchant critics of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. While India’s Opposition have harsh words to say about Modi, the Bharatiya Janata Party, and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, it may not be at ease when the attacks stem from the government of a hostile neighbour. The invocation of the 2002 Gujarat riots wasn’t the first occasion that Pakistan has jumped in to make gratuitous comments on India’s internal politics. Whether it was the Ayodhya dispute, a communal riot or other issues confronting Indian Muslims, Pakistan has rarely lost an opportunity to provide its own running commentary.

A large part of this distressing habit stems from a deeply ingrained belief in Pakistan that India’s unity is fragile, and that sooner or later fissiparous tendencies will prevail. Consequently, and not least in retaliation for India’s role in breaking up Pakistan in 1971, Islamabad has deemed it necessary to provide both covert and overt support to movements that have separatist potential. Apart from nurturing an insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan has given generous support to the Khalistan movement in Punjab, not to mention the more modest assistance to the many separatist movements in the Northeast.

While opportunistic support to potentially disruptive forces in India has been a facet of Pakistan’s unending bid to weaken its more powerful neighbour, it is guided by expediency. If the situation so demands, Islamabad will not hesitate to wash its hands off the Khalistanis who they now count as assets. However, a similar cynicism is unlikely to guide Pakistan’s approach to issues governing India’s Muslim minority. The reasons are grounded in history.

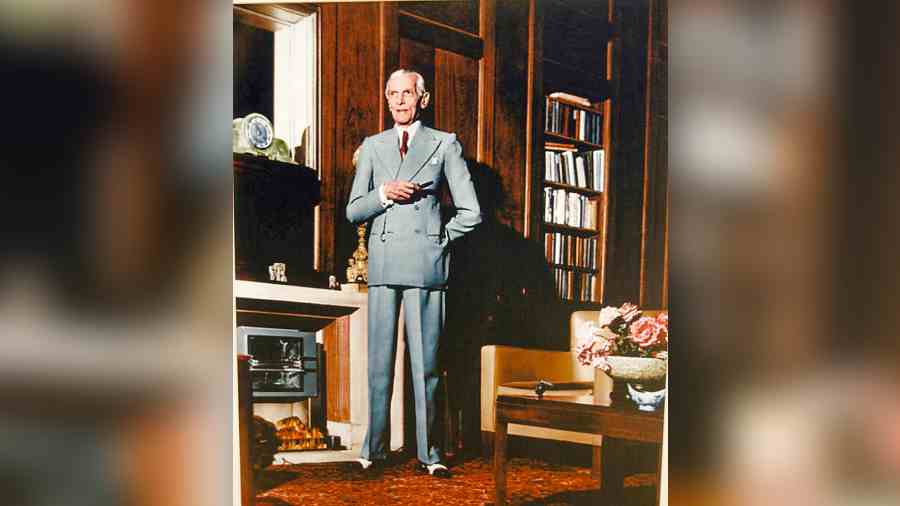

Regardless of the contemporary significance of the major ethnic communities — Punjabis, Sindhis, Pathans and Baluchis — that constitute the four pillars of Pakistani nationhood, it is important to bear in mind that undivided India’s Muslim-majority provinces were relative latecomers to Muhammed Ali Jinnah’s movement. (Bengal may have been the exception.) Pakistan, in the eyes of its founding fathers, was a movement for a Muslim homeland in the Indian subcontinent, a place where Indian Muslims could live and prosper without being constrained by the Hindu majority of India. The greatest appeal of the Pakistan movement from its inception in 1940 to the elections of 1946 was among the Muslim minority in places such as the United Provinces, Bihar, Central Provinces, and the Bombay Presidency. The Muslim middle classes from areas that were not destined to be included in Pakistan constituted the leadership of the Muslim League. For those who left their ancestral homes in India to make a new beginning, Pakistan was the promised land.

Yet, the vast majority of those who supported the demand for Pakistan by the Muslim League didn’t migrate to either of the two wings of Pakistan. The likes of Jinnah, Liaquat Ali Khan, Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman and H.S. Suhrawardy, the men who played an important role in Pakistan in its early years, all came from places that were not included in Pakistan. They, above all, were mindful of the fact that a very large Muslim minority was to be left behind in Hindu-majority India. The founding fathers of Pakistan counted the Muslim minority of India as Pakistan’s natural responsibility, just as India counted the Hindu minority of East Pakistan as its own people. Indeed, it is interesting to note that Suhrawardy, who, despite being the last premier of united Bengal was replaced by Khwaja Nazimuddin as chief minister of East Pakistan, opted to stay behind in Calcutta till 1950, ostensibly to look after the interests of the Muslim minority of West Bengal. This was also the case with Syed Badrudduja, a Muslim League stalwart and the former mayor of Calcutta.

The significance of India’s Muslim minority to Pakistan can be gleamed from two memoirs by army officers, written in the aftermath of the 1971 Bangladesh debacle. The first, A Stranger in My Own Country: East Pakistan, 1969-1971, by Major General (Retd) Khadim Hussain Raja, contains a small description of a Haj pilgrimage he undertook in February 1969, a time when Pakistan was convulsed by an anti-Ayub Khan movement in both wings of the country. During the pilgrimage, he met many Indian Muslims. “They… expressed the view that Ayub Khan had built up an image of Pakistan as a strong and prosperous country that was a force to reckon with. The Indian Muslims were particularly distressed since Pakistan’s strength, as a country, and its leadership, were, by proxy, a source of pride and reassurance for them in their unenviable predicament as a victimised minority…”

The second, The 1971 Indo-Pak War: A Soldier’s Narrative, by Major General (Retd) Hakeem Arshad Qureshi, described his journey to captivity in Ranchi after the surrender. “At long last we reached Ranchi… From the railway station, we were transported to the POW camp by requisitioned trucks. I sat on the front seat with the driver. It was here that I realized how much damage our surrender had caused to the Muslims in India. The driver, a Muslim, was in tears. The Muslim population of India was deeply concerned about the effect that our abject capitulation would have on them as a community.”

The accounts may not be entirely representative, but it suggests that as far as the Pakistani Establishment was concerned, bolstering the interests and the self-confidence of the Muslim minority was Pakistan’s natural responsibility. It also suggests that the debacle in Bangladesh was a devastating blow to the status of Pakistan as a defender of the ummah. This may explain why, in the aftermath of the demolition in Ayodhya on December 6, 1992, and the Bombay riots in January 1993, Pakistan linked up with Dawood Ibrahim to facilitate retaliatory blasts that killed nearly 300 people. Pakistan’s nurturing of Islamist terror in India from the late1990s was also its way of recovering its standing among Indian Muslims — a complement to its role in the troubles in the Kashmir Valley.

Whether or not this will restore the faith of a new generation of Indian Muslims, now habituated to viewing Pakistan as a State on the cusp of a breakdown, is a different issue altogether.