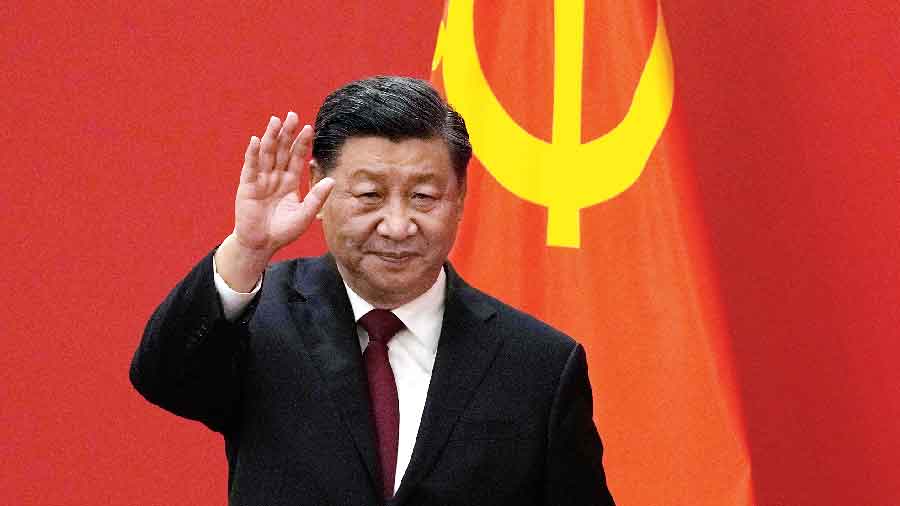

Like all good autocrats, the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, has purged the top Chinese Communist Party hierarchy of even a semblance of diversity. There is no attempt to showcase the collective leadership model of yore. Instead, it is all about Emperor Xi.

After getting an unprecedented third term, thereby breaking a longstanding tradition, Xi has come up with a new Politburo Standing Committee with members who are close allies of the president. If the removal of Li Keqiang, the outgoing premier, was a signal that no one is indispensable, the ushering away of Hu Jintao in public glare was a statement about the marginalisation of the old guard.

The 20th Party Congress was a demonstration of Xi’s might and unparalleled power despite the lone wolf protest at the beginning. The unveiling of the Standing Committee and the 24-member Politburo underscored Xi’s tightening grip on the nation’s political structure even as amendments were added to the party charter cementing his core status as well as the guiding role of his political thought within the party.

In 2018, Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era was enshrined in China’s Constitution and the two-term limit on the presidency eliminated. Since then, it has been Xi’s way as he has gone about consolidating his legacy almost on a par with Mao Zedong. At the Congress, all party members were obliged to “uphold Comrade Xi Jinping’s core position on the Party Central Committee and in the Party as a whole”.

Loyalty is the most prized possession in Xi’s China. His top team includes his closest allies. Performance does not matter anymore. The former Shanghai party chief, Li Qiang, will be the new premier in charge of economic affairs despite his abysmal record in managing the lockdown in Shanghai. Cai Qi’s appointment to the Politburo Standing Committee is also a case in point. On the other hand, Li Keqiang as well Wang Yang, seen as a contender for Xi’s second-in-command role, were dropped to underline the message of one supreme leader.

China is becoming ever more tightly controlled by a coterie within the CCP. It is turning inwards and becoming even more conservative under Xi. By announcing his new team in his own image, Xi has ensured that his power and privilege would remain protected from internal challenges for the foreseeable future. Also, for the first time in a quarter century, no woman has been appointed to the Politburo, a stark reminder of how closed the power structure of the CCP is.

After taking an aggressive tone at the beginning of the Congress, Xi tried to be reassuring in his closing remarks when he suggested that “China’s door to the world will only get wider,” and that China “will stay committed to comprehensively deepening reform… promoting high-quality development, and creating more opportunities for the world through our own development.” Xi understands that his policies — domestic and foreign — have created an intense backlash that is likely to spell trouble for his ambitions. The economic growth rate is slumping and globally China is facing a pushback from nations that view Beijing’s uncompromising attitude as a long-term strategic challenge. Xi is now elevating security to the top of his policy agenda as he intends to keep China on a perpetual ‘high alert’. Contestations with the United States of America and the West are likely to be the central features of Xi’s narrative as he pushes ahead with heightened domestic nationalism to stave off the challenges that have emerged from his ill-conceived policy choices.

As Xi starts his third term, it is a reminder of how drastically he has managed to change China over the last decade. In the process, the global perception of China and its leadership has also undergone a dramatic — negative — transformation. The world is carefully assessing the Xi era. But it is unlikely that rectifying global perception of China is going to be a priority for Xi and his coterie any time soon.

Harsh V. Pant is Professor of International Relations, King’s College London