Society tends to resist women’s inheritance rights. Male members of the family often laid claim to the property of a man who died intestate, or acted as self-appointed ‘guardians’ for the bereaved woman with an eye on benefits. Many states still baulk at registering property in women’s names. The dowry given to a daughter at the time of marriage complicated matters too; male heirs could insist that after this share in the father’s wealth the daughter could have no moral claim to his estate. The Hindu Succession Act, 1956, however, had made the daughter’s right to her father’s property perfectly clear. The Supreme Court has now reportedly pronounced that a daughter’s right to inheritance would apply even before 1956. The case came to the highest court on appeal, after the trial court and the Madras High Court had dismissed a woman’s claim to one-fifth of her father’s inherited property among five heirs. The property had originally passed from a father to a daughter when he died intestate before 1956. After the daughter died without children in 1967, the property was inherited by a male heir on the father’s side, whose daughter laid claim to one-fifth of it.

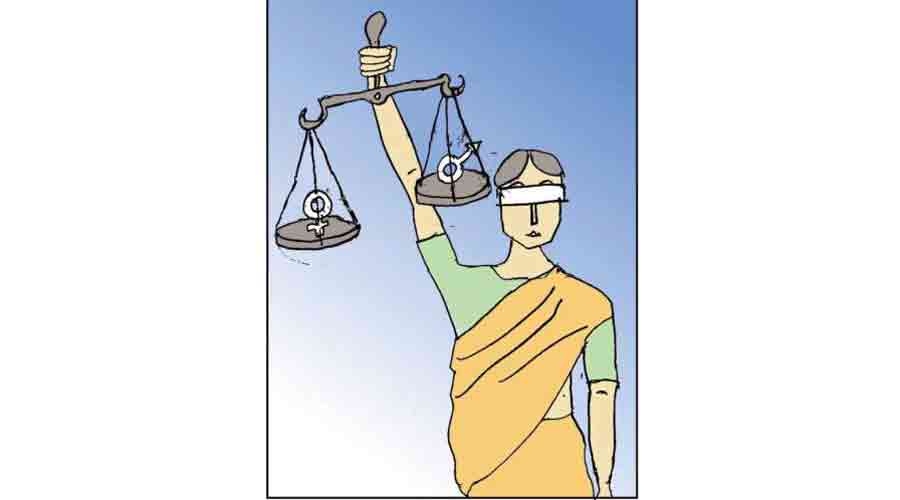

The Supreme Court used the examples of old Hindu customary laws and earlier judicial pronouncements to show that even before the Hindu Succession Act wives and daughters had equal rights with sons to a man’s self-acquired property or that acquired by share in a joint estate. These women’s inheritance rights superseded the survivorship claims of other males in the family. The court’s emphasis on the provisions of the Mitakshara law of inheritance showed that both traditional and modern laws were fair, humane and without a hint of misogyny. It is ironical that women in India need to fight for equality and justice in every sphere, even for survival amid violence, cruelty and exploitation, where the law grants them equality without being asked. Yet state laws and personal laws may still reject this forward-looking vision, especially where agricultural land is concerned. In Uttar Pradesh, for example, married daughters are not primary heirs. This is just one instance among many that demonstrate women’s difficulties in accessing rights and controlling inherited property. Society has far to go to catch up with the progressive understanding of the Supreme Court.