Bidding farewell to the dead through funeral rites was one of the earliest signs of civilization. Although funeral practices have changed with time, bereavement is still an event. People wish peace for the dead through rituals according to their cultural and religious beliefs; it is a way of coping with the unknown. Social bonds are confirmed in the period of mourning through sharing and support. It is understandable that a pandemic would disrupt these systems, especially when the disease causing it is infectious. India has seen the horrors of many epidemics — cholera, smallpox, plague, Spanish flu — which were often marked by the breakdown of funeral practices. But this is not the 19th century, neither is it the early 20th. There is something deeply shocking in the desperate need of the families of a huge number of victims of the virus to ensure a basic funeral. Queues at overflowing crematoriums and burial grounds and hundreds of constantly burning pyres are painful enough — pyres had to be built in a car park too — but what seems unbearable is that people are being forced to bury bodies in the shallow soil of river banks or let them float away, sometimes partially cremated and sometimes not at all.

It is as though the roots of society are being torn apart, for the cultural and psychological damage caused by this unprecedented crisis is incalculable. Certain actions by the political leaders of this country could have reduced the enormity of the disaster, if not kept it fully under control. If helpless citizens are unable to accord their loved ones minimum dignity in death because, perhaps, no one is around to take the bodies for cremation, or they cannot afford the soaring prices of wood or the funeral — profiteers never rest — and have to throw bodies into the river, this has to be laid at the door of the administration. The National Human Rights Commission has, by implication, done just that in its list of instructions aimed at securing the dignity and rights of those dead. A legislation to establish these rights must be enacted, it has said among other things, while the administration must arrange for temporary crematoriums, stop the piling up of bodies during transport as well as mass burial and cremation, control price hikes of ambulances and hearses, and vaccinate crematorium and burial ground staff.

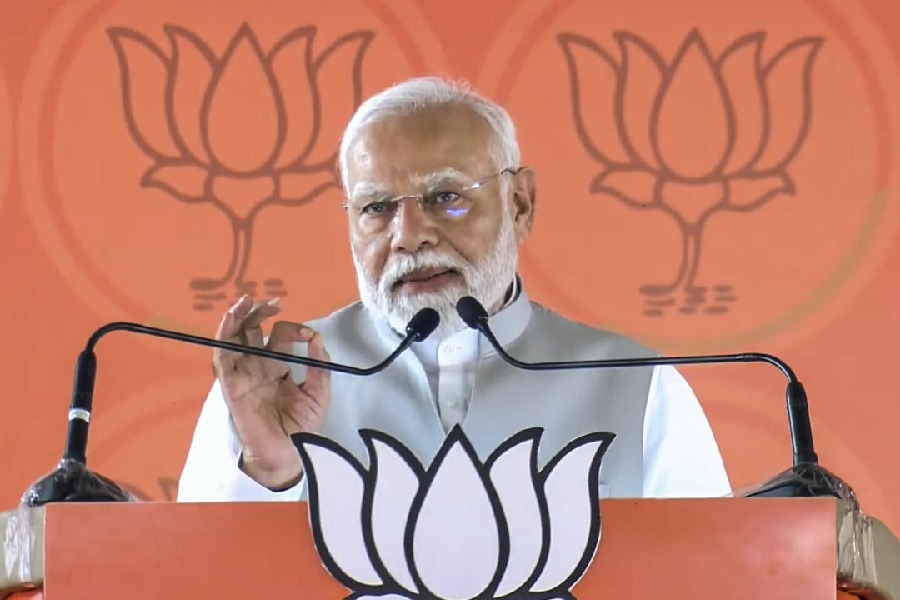

The NHRC’s concern carries some impression of the magnitude of today’s humanitarian crisis. India is a grieving country. The political leadership at the Centre, however, still feels that its priority is propagating the image of a busy, strong, quietly working prime minister, while his party continues to sniff around for causes to disturb the new government in West Bengal, a state overrun with tragedy. The prime minister has spoken at last, saying he feels the people’s pain. Some in desperate need and sorrow may find that a little difficult to appreciate.