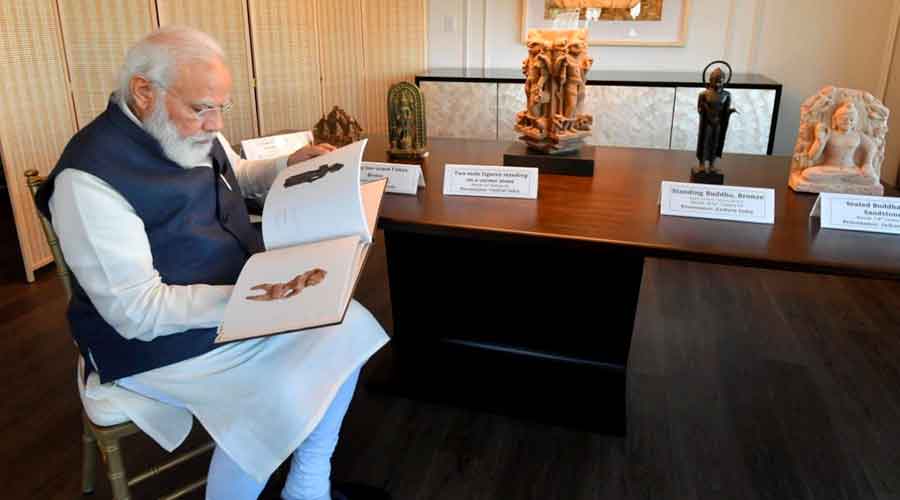

Homecomings can be bittersweet. The prime minister, Narendra Modi, brought home 157 stolen artefacts and antiquities, which were handed over to him by the United States of America. Ironically, though, tangible heritage faces a serious threat of obliteration in a New India obsessed with a mythical past. That could be because priceless artworks are, at present, protected by the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, 1972. As antiquated as the items it seeks to protect, this law has many shortcomings. Excessive bureaucratic hurdles for both owners and traders of antiquities and the lack of a provision for a comprehensive database of such items are just two such gaps. These loopholes have helped create a thriving black market in these riches. The law also betrays ignorance about the vastness and the intricate nature of the international smuggling racket that comprises diverse agents, including ragpickers and impoverished middlemen. Livelihood exerts greater pressure than ethics. There is thus scope for introducing incentives and protection in the law for the accomplices so that they are encouraged to disclose information about those involved in illegal trade to the investigating agencies. The draft antiquities and art treasures regulation, export and import bill, 2017, which was supposed to replace the 1972 Act still lies in a limbo. Worryingly, it proposes to do away with the requirement of a licence for selling antiques within the country and the need to authenticate provenance or declare the source of acquisition of the pieces. This could end up facilitating the existing unlawful trade in invaluable material heritage instead of protecting it.

The return of the artefacts from the US should be an occasion to reflect on these failings and examine possible solutions. First among these would be institutional reforms. Museums and the Archaeological Survey of India should employ trained staff. The director-general of the ASI — vested with the power to determine whether an idol is an antiquity — must have extensive expertise in archaeology and conservation. There is also the need to sensitize allied institutions, such as the police and other investigative agencies usually tasked with retrieving stolen artefacts, about the importance of heritage. The challenges that the police face — shortage of funds, manpower and autonomy — make it difficult for India to raise a specialized unit, such as Italy’s Carabinieri, whose officers would be trained not only in investigative techniques but also in art history and international law. The greatest impediment, of course, is India’s casual attitude towards antiques. The pedagogy of history and art objects needs to be made popular.