Commenting on the success of the Bharat Jodo Yatra, the Congress leader, Jairam Ramesh, made an interesting point. He said, “… through the Bharat Jodo Yatra… we have succeeded… to set the terms of debate and the narrative in the political discourse” (https://www.thehindu.com/ news/national/playing-against-bjp-oncongress-prepared-pitch-due-to-yatrajairam-ramesh/article66277429.ece).

Ramesh, like many other serious non-BJP politicians, employs the term, ‘narrative’, to underline the contested nature of public debates, especially in the electoral arena. Although he did not use the word, Hindutva, in this interview, he acknowledged the capacity of the Bharatiya Janata Party to set the conditions for a particular kind of idea to survive in public discussions. The BJY, in his view, is a crucial event that has given an opportunity to the Congress to get rid of this given framework. In other words, an alternative narrative of politics is being unfolded.

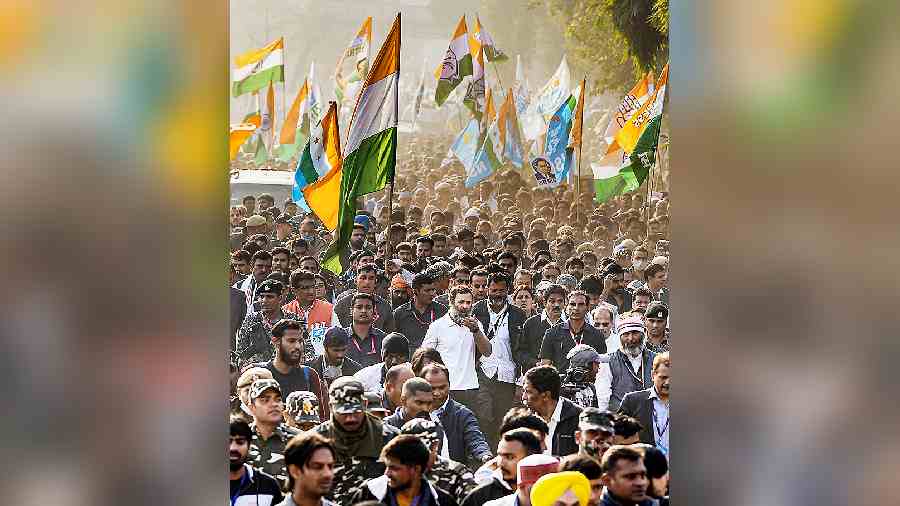

No one can deny the significance of this political comment. It is true that the Congress, as the main Opposition party, has come out with an original and constructive idea of a yatra to carve out an intellectual space for itself in the Hindutva-dominated political environment. The active participation of liberal and progressive intellectuals, civil society organisations and representatives of people’s movements has also contributed significantly to this process. It will be too early to make a conclusive remark on the outcome of the yatra. Yet, Ramesh’s comment offers us an opportunity to briefly explore different postcolonial political narratives that have evolved in specific historical contexts.

The terms, ‘narrative’, and, for that matter, ‘political narrative’, are used freely to convey a number of different, even contradictory, expressions. It is, therefore, important to underline the specific sense in which ‘narrative’ is used in the contemporary Indian public discourse. Broadly speaking, a political narrative is a description of a set of identified events/individuals arranged in a particular sequence to produce ideologically suitable political explanations.

Socialism was the first dominant narrative of Indian politics. It began to take concrete shape in the 1940s itself. Although the word, socialism, was not included in the Preamble of the original Constitution, it was one of the most seriously discussed themes in the Constituent Assembly. The outcome was obvious: the Constitution was not officially socialist, yet it was committed to the idea of social justice and economic equality.

The first general election was an interesting experiment at the ideological level as well. The success of the Congress, the communists and the socialists in the 1952 elections forced all political players to recognise socialism as a reference point to reconfigure their future ideological positions. The Congress adopted Jawaharlal Nehru’s socialistic pattern of society thesis, the Communist Party of India followed the ideal of ‘people’s democracy’ to achieve socialism, and thinkers like Ram Manohar Lohia and Jayaprakash Narayan made serious attempts to redefine socialism in the Indian context. Interestingly, parties like the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, which was committed to Hindu nationalism, also recognised socialism as an important consideration. In fact, Deendayal Upadhyaya described socialism “as a force” to claim that the BJS was “… socialist in its emotional and ideational appeal” (http://deendayalupadhyay.org/ national.html).

The Emergency period (1975-77) was perhaps the most significant moment in this regard. The Indira Gandhi regime amended the Constitution to formally insert the term, socialism, into the Preamble. This move helped the Congress government to legitimise its authoritarian policies without deviating from the acceptable narrative of politics.

A few critical events of the 1980s — the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the Shah Bano case, and the Babri Masjid-Ram temple controversy — destabilised the narrative of socialism. Although socialism as a concept continued to survive, the political class found it rather irrelevant to deal with the growing influence of religion in public life.

Around the same time, the policy framework also went through a decisive change. The market economy and liberalisation were accepted as the ultimate form of economic system in the 1990s. This new political consensus in favour of the market transformed the State into a mediating agency to resolve societal conflicts.

In this highly volatile context, secularism emerged as the new dominant narrative of Indian politics. The Congress established itself as the leader of the secular camp after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992. The BJP and the Shiv Sena were symbolised as communal parties in this schema. Interestingly, the BJP also accepted secularism as a point of reference to legitimise itself, especially in the domain of electoral politics. Criticising the secularism of the secular parties as ‘pseudo-secularism’, BJP leaders made a strong claim in favour of what they called ‘secularism without appeasement’.

The narrative of secularism started to fade away in the late 1990s. The BJP gave up three controversial issues — the Ram temple, Uniform Civil Code and Article 370 — to lead the National Democratic Alliance. On the other hand, the non-NDA forces were desperate to evolve a broad ideological consensus that could give them a new language to survive in the electoral arena.

The 2004 election was a turning point. Secularism was not given up completely by the newly-formed United Progressive Alliance government. Instead, it was redefined as one of the constituents of what was called politics of social justice and inclusiveness. It paved the way for the third dominant narrative of politics — inclusion. This narrative was based on a premise that the marginalised social groups — women, children, Dalits, adivasis, unorganised labour, minorities/ Muslims and so on — were to be seen as stakeholders. In this schema, the State was envisaged as an agency to facilitate welfarism as sectoral empowerment in such a way that the commitment for free market could not be compromised.

The narrative of inclusion was rather short-lived. The anti-corruption movement of 2011 followed by the protests against the gang-rape in Delhi in 2012 were the watershed events. Nationalism made a decisive comeback through these protests. The national flag, copy of the Constitution, and images of national figures were used by the protesters to make an argument that the country needed a truly nationalist government. This wider acceptability of nationalism had two, very clear manifestations. The newly-formed Aam Aadmi Party defined nationalism in terms of service delivery, while the BJP introduced Narendra Modi as the decisive leader to reclaim nationalism in overtly Hindutva terms. The electoral success of the BJP in the post-2014 period actually helped the Hindutva-driven nationalism to become the contemporary narrative of Indian politics.

These four clearly identifiable narratives — socialism, secularism, inclusion and Hindutva-driven nationalism — dominate, survive, overlap and compete with each other in the real world of politics. Any search for an alternative narrative must recognise them as available intellectual resources to evolve a futuristic, pragmatic and action-oriented political resolve. It will be interesting to observe how the BJY and the Congress establishment engage with these narratives. After all, politics is all about ideas and perceptions.

Hilal Ahmed is Associate Professor, CSDS, New Delhi