A major reason for unemployment in any economy is that some of its members prefer goods produced outside the economy to those produced within it by other members. This is what had caused unemployment and deindustrialisation under the colonial regime: imported, machine-made British cloth had been preferred to home-produced cloth not just by the landlords but by the peasants as well, which had reduced the demand for the latter and created mass unemployment among the weavers. Now too, imported Chinese lights, for instance, are preferred by many to home-produced candles and lamps even on Diwali day; instances like this constitute one reason for the unemployment and crisis afflicting the domestic petty production sector.

The reason for such import-preference lies in the price- or quality-superiority of the imported good over the home-produced one, which, therefore, gives rise to a serious policy dilemma: should a country protect domestic production and employment against imports when such protection causes a reduction in the standard of living of a section of the population that benefits from the price- or quality-superiority of the imported goods?

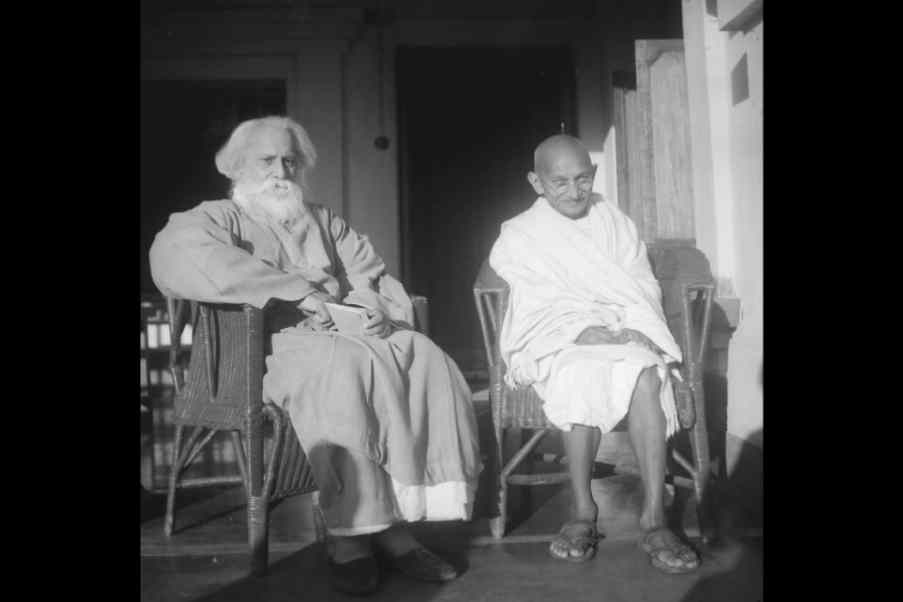

This is an issue on which two of the tallest figures of modern India, Rabindranath Tagore and M.K. Gandhi, had differed. (Incidentally, for any student of the Indian economy, the correspondence between these two, including pieces where they do not directly address one another, that have been conveniently brought together by Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, provides in my view the best reading even to this day). Gandhi was concerned with unemployment. He was, of course, not talking about protection against imports; and the colonial State in his time could hardly have been expected to protect domestic employment against imports. But he wanted people to boycott foreign goods so that domestic producers did not lose their employment. To paraphrase him: “how can I deck myself up in the finery of Savile Row when I know that my doing so starves my brother the weaver in the next village?” His appeal was on ethical grounds, that the beneficiaries of imported goods should make a sacrifice for the sake of their local artisan brothers.

Tagore’s position, which had also informed his novel, Ghare Baire, was the opposite of this. If the peasantry, constituting the backbone of Bengal’s rural life and acutely oppressed by colonial exactions, managed to access better quality or cheaper cloth, then that should be a source of some relief; snatching away even that relief could not possibly be justified. (He was also acutely aware of the potential for communal conflict that such snatching away could generate since the peasants belonged largely to the minority community while the political movement against foreign goods was led by an elite belonging to the majority community; but I shall not go into this aspect here.) There was in his view no pressing ethical argument for boycotting imported cloth; ethics, if anything pointed in the opposite direction, of supporting the import of cloth for an improvement in the standard of living of the hard-pressed peasantry of Bengal.

Modern-day economists would leave the matter there, without sticking their necks out by supporting one or the other position. It is for ‘society’, they would argue, to make up its mind about whether to privilege the employment objective over cheap imports, or how exactly to strike a balance between the two. While they may have their own personal preferences between the two objectives, as economists they would claim they cannot say anything further on the subject, especially since both peasants and artisans are poor and no judgment on egalitarian considerations can be made in favour of either.

Even analytically, however, leaving the matter there is unwarranted; something much further can be said on the subject when we take a slightly longer view. Colonial deindustrialisation, for instance, while appearing to constitute immediately a price to be paid for cheaper imports that improved the living standards of the peasantry, entailed over a period of time a worsening of the living standard of the agricultural population. It increased the pressure of population on the available land, since the unemployment generated by it forced masses of displaced petty producers into seeking a livelihood in agriculture. As the investment for increasing either the gross cropped area or the yield per acre was not forthcoming from the colonial government, displaced petty producers turning to agriculture meant an increase in land-rents and a decrease in agricultural wages during the nineteenth century that hurt the agricultural population, the very population that is supposed to have benefitted from cheaper cloth imports. (This income effect is noted in Bipan Chandra’s “A Reinterpretation of Nineteenth Century Indian Economic History”, IESHR, 5(1), 1968).

The main beneficiaries of the cheaper cloth imports in the nineteenth century, taking both the immediate price effects and the long-term income effects, would have been the landlords and not the peasants who appeared immediately to have been the beneficiaries as well. It follows that the employment objective had to be socially prioritised on egalitarian grounds which most people would accept as ethically legitimate.

Two conclusions follow from this: first, analysis has to be pushed much further than appears warranted at first sight, since the full effects of any course of action take much longer to unfold; and second, the effects of unemployment are far more damaging than appear immediately, and hence its removal must claim social priority. In fact, the essence of economic development must consist not in achieving a higher growth of the gross domestic product per se, but in overcoming unemployment (and underemployment) even at the expense of cheaper imports if necessary.

Prabhat Patnaik is Professor Emeritus, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi