South Asian politics has not been the same since the Covid-19 pandemic. In a region known for its chequered political history, anti-incumbent sentiments seem to be running high. A series of recent events tells a larger story about democracy in South Asia.

The hasty withdrawal of American forces from Afghanistan in 2021 witnessed the Taliban’s return to power, signalling a reversal for the tiny democratic advances made by the nation. The removal of Pakistan’s former prime minister, Imran Khan, from office in 2022 reflected, once again, the fragility of democratic regimes in this South Asian country that is no stranger to military rule. A subsequent assassination attempt on Khan, his conviction and imprisonment in a corruption case, and his failure to return to power even as his outfit, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, emerged as the single largest party in the general election demonstrated that democratisation remains a long walk for Pakistan.

In two other South Asian nations, mass protests ousted democratically-elected governments. First, Sri Lanka’s then president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, was removed two years ago following discontent over his alleged mishandling of an economic crisis. Now, Sheikh Hasina Wazed has had to resign as Bangladesh’s prime minister over massive protests that began with an agitation against a quota system.

Democratic theory conceptualises democracy into procedural and substantive categories. The former is centred solely on electoral processes, so much so that even essentially undemocratic regimes hold non-competitive elections to enhance their legitimacy before the global order. The idea of substantive democracy, on the other hand, transcends procedural formalities to encompass the resilience of institutions, civil liberties and citizenry rights, social outcomes and the quality of life, amongst other factors. South Asian democracies seem to be largely complacent about exaggerating their electoral aspects while performing sub-optimally in between elections. The growing ethnification due to polarisation seems to be deepening the existing social cleavages, stirring up majoritarian proclivities and further accentuating the democratic backsliding, thereby contributing to the emergence of illiberal democracies that are electorally viable but substantively compromised.

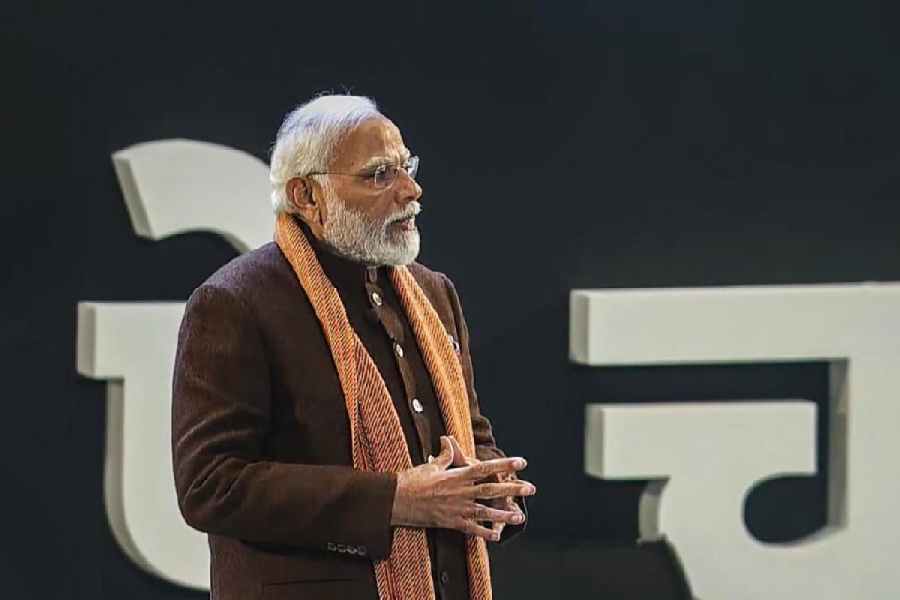

Even in the more stable democratic regimes of South Asia, public antipathy towards the incumbent has found strong resonance. Nepal, which has witnessed a sea of political change since the inauguration of its new Constitution, continues to be ruled by unstable governments with the latest turnover taking place as recently as July when an alliance of the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) and the Nepali Congress dislodged the government of Pushpa Kamal Dahal. The Bhutanese general election also signalled a change of guard with the return of Tshering Tobgay and his People’s Democratic Party to power. The Maldives elected a new president with Mohamed Muizzu, who had called for the withdrawal of Indian forces from the island nation, beating the incumbent. In September, the presidential election in Sri Lanka sprung a surprise by electing the lesser-known Anura Kumara Dissanayake. India, too, saw a stronger performance by the Opposition in the Lok Sabha elections, vindicating anti-incumbency sentiments of varying degrees.

Weakening institutions and contracting democratic space have perhaps forced extra-parliamentary activism and made popular movements the new mainstream as diverse voices failed to find adequate articulation through institutional avenues hinting at a larger churning within South Asia with dangers of a possible spillover into other regions of the world, including the West.

Soumyadeep Chowdhury is an ASAP Fellow at Yale University