Although I grew up in North India, the newspaper that came into our home was headquartered in a great city then called Calcutta. This was The Statesman, whose main edition was published in the first capital of British India, but which had a small subsidiary edition printed in the second and last capital of the raj. It was this Delhi version of the newspaper that came into our home in Dehradun, arriving around noon via a transportation process that involved road, railway, human hands, and human feet on a bicycle.

My father subscribed to The Statesman for three reasons: he thought it had (of all Indian newspapers published in English) the fewest solecisms and the fewest misprints, and because a favourite nephew of his had once worked there. I grew to like the paper myself, and for my own reasons: for its excellent coverage of foreign affairs: I recall with particular fondness James Cowley’s ‘London Notebook’ — for its humorous third leader and for having as a columnist the naturalist, M. Krishnan, a master of English prose.

When I went to university in Delhi, I continued to subscribe to The Statesman. However, in the five years I spent acquiring two desultory degrees in Economics, I witnessed the paper undergo a steady decline. Although Krishnan remained, Cowley had left; and so also many of the other writers I once liked reading. More disturbingly, the wall between editorial and management had been breached, with a senior executive of the newspaper violating custom and propriety by starting a signed, and altogether unreadable, column of his own on the front page.

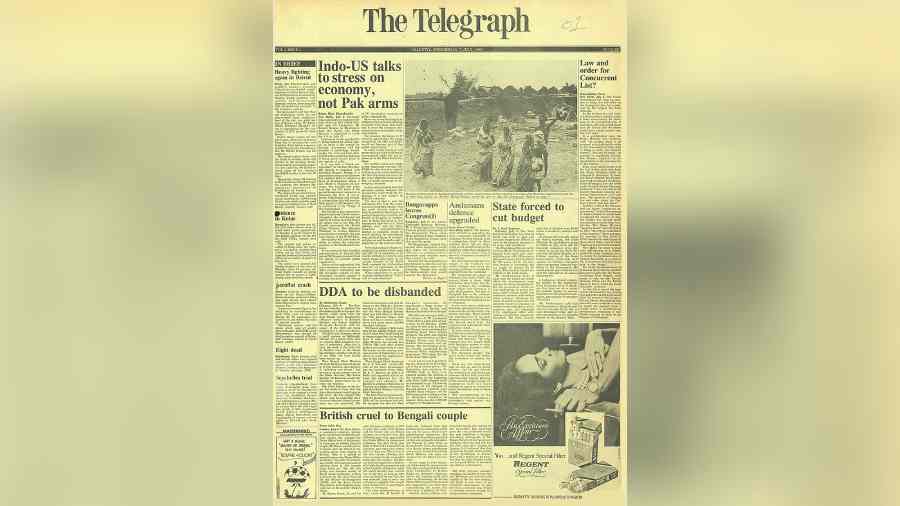

In 1980, I moved to Calcutta to begin a doctorate in sociology. Had I stayed on in New Delhi, I might have subscribed to The Indian Express, but that paper had no Calcutta edition so I was stuck with The Statesman, now in its death throes but still insistent on coming out every day. It was therefore with both relief and excitement that I greeted the publication of the first edition of The Telegraph, printed on July 7, 1982. The young man who delivered newspapers on our Institute’s campus was as excited as I: for he came into our hostel waving this new newspaper (we hadn’t yet become accustomed to think of such things as ‘products’) saying, “Telegram! Telegram!” It was an endearing solecism, and one part of me still cannot think of this newspaper as being called anything other than ‘Telegram’.

One of the first things that struck me about The Telegraph was how elegantly produced it was. My aesthetic sense, previously dormant, had been awakened by having dated for some years past a girl from Bangalore studying graphic design in Ahmedabad. But even without the benefit of this relationship, I might have been able to see how much more attractive The Telegraph was to hold, feel and see than not just The Statesman but The Times of India and The Indian Express as well. The type looked better and read easier than in any other Indian newspaper of the time; the masthead was striking without being, as it were, ‘in your face’; and there was a far greater, and more effective, use of photographic images than in its competitors. And, as I was to soon discover, the content matched the form, with the reports, commentaries and editorials all being richly readable.

Among the founding team of The Telegraph was an old college friend of mine, Paranjoy Guha Thakurta. I sometimes made the long trek from my Institute at Joka to the newspaper’s office at Prafulla Sarkar Street to see ‘Thak’, as he was known, reaching my destination by a combination of bus, tram, minibus, and my own two feet. The newsroom hummed with action and excitement; here was a group of young people determined to breach The Statesman’s citadel and become the English newspaper of choice in Calcutta. And they hoped to make a wider, all-India impact, too.

Thak asked whether I had an article to contribute to the newspaper. As it happened, a new forest bill had been drafted by the Government of India and I had written a pungent critique of it. Thak urged me to submit the article to The Telegraph for publication on its op-ed page. I did, and it was accepted, but the day before the article was to appear in print, Amitabh Bachchan suffered a serious injury on the sets of a movie called Coolie. With the most famous man in India (the prime minister was a woman) hovering between life and death, the publication of a piece on a subject as arcane as forest law was postponed indefinitely. I finally had it published (again, at Thak’s suggestion) in the columns of the Business Standard, which was then a sister newspaper of The Telegraph, with the same proprietors.

Had Mr Bachchan not been injured on a movie set, I might have had a piece published in The Telegraph the very month the newspaper was born. As it turned out, the first time my byline appeared in this newspaper was a decade later, when I had an essay on the anthropologist, Verrier Elwin, printed on the occasion of his ninetieth birth anniversary (August 29, 1992). In the decade that followed, I began to write episodically for the edit pages, perhaps eight or ten pieces a year. Then, on November 15, 2003, I commenced a fortnightly column in The Telegraph, called ‘Politics and Play’, of which this is (by my calculations) the four-hundredth-and-eighty-third installment.

I have had the privilege of writing a column in The Telegraph for close to two decades now. In this period, I have also had regular columns in three other Indian newspapers. When I felt writing for the press did not give me enough time to research and write my books, I have, one by one, given up these other outlets while retaining my connection to The Telegraph. I have also turned down invitations to write columns for foreign newspapers, choosing to focus my energies — such as they are — on this column instead.

As a reader, The Telegraph is my newspaper of choice for several reasons. These include: the spark and liveliness of its prose, the intellectual/ideological range of its columnists, the fact that it still has a full page every week devoted to books, and the humour and mischief of its headlines. It also remains the most visually appealing of all the newspapers printed in this country. I should also perhaps explain why, as a columnist, I have a special fondness for The Telegraph. There are three reasons, which I give here in ascending order of importance. First, unlike most other Indian media outlets, The Telegraph pays its contributors promptly. Second, since it was Calcutta that gave me a chance to become a scholar, I feel I must repay my debt to the city (and intellectual culture) to which I owe so much. Third, unlike other Indian media outlets, the newspaper does not succumb to political or economic or social pressure when it comes to the views of its columnists. I continue to write in The Telegraph because I can say things here about Indian politicians, businessmen, generals, government officials, and cricketers, that despite being true, sometimes cannot be said in English newspapers printed in other Indian cities and owned by other sorts of people.

The independent-mindedness of The Telegraph owes a great deal to the imprint of its founder, Aveek Sarkar. He was that rare editor/proprietor of a newspaper in India — one who did not want a Rajya Sabha seat or any other sort of sarkari recognition for himself. He also believed that a newspaper must reflect all shades of intellectual and political opinion. A passionate anti-communist, he nonetheless gave columns in this newspaper to prominent Marxist scholars, who shared space with conservatives and reactionaries as well as liberals like myself.

There was a time when I could get the print edition of The Telegraph in Bangalore, from a news vendor located outside the only branch of K.C. Das outside Calcutta. It was, as it were, sandesh and rasamalai for my eyes. Sadly, that vendor has long since shut down, and I must make do with reading it online instead. For four decades now, I have been one of the newspaper’s most devoted readers; and for about half that time, a regular contributor. It is in both capacities (but especially the first) that I wish The Telegraph a happy fortieth birthday.

Postscript: In thirty years of writing for The Telegraph, its editors have tried to ‘kill’ a piece of mine only once — in the present instance. They thought I should write about my relationship with the paper elsewhere, but I insisted that it be published here, for to ‘censor’ this piece would be trampling on a columnist’s prerogative to write as he wishes, as well as violating the norms of non-interference that the paper had established in the first place.