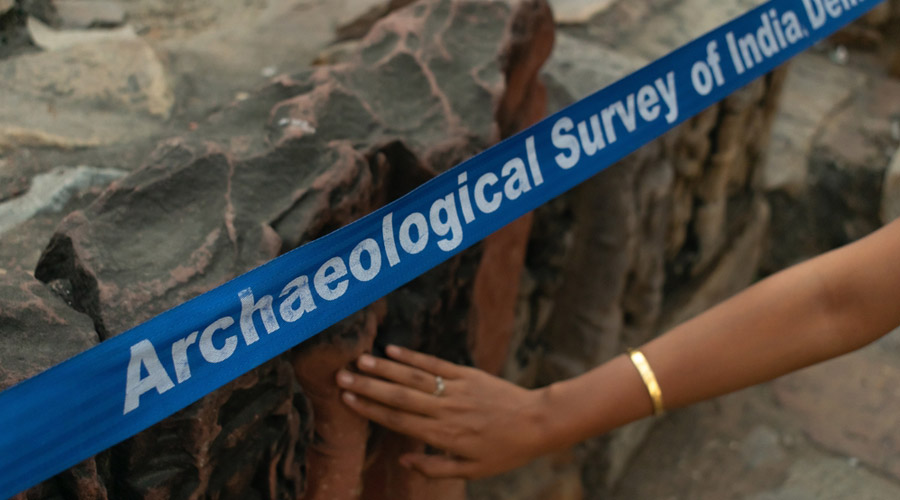

The Union minister for culture and tourism, G. Kishan Reddy, recently intimated Parliament that 356 Centrally protected monuments have suffered encroachment. The largest number of infringements occurred in Uttar Pradesh, while Tamil Nadu, with 74, saw only one less incident. Karnataka, Maharashtra and Gujarat make up the top five with 48, 46 and 35 encroachments, respectively. The reasons for these transgressions are numerous. Commercialisation and urbanisation, augmented by the lax supervision of laws, have led to such encroachment. Despite new construction being prohibited within a 100-metre radius of a heritage structure, numerous business establishments have been set up, at times, literally on the walls of temples and other structures — Pune’s Tulshi Baug is one example. Moreover, government bodies remain embroiled in turf wars. The ambiguity in jurisdiction between the Archaeological Survey of India, responsible for the preservation of monuments of national importance, and the National Monuments Authority, which was set up under the 2010 amendment to the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, has given rise to numerous conflicts. In 2015, the ASI stated that the NMA had no authority to impose fines and issue recommendations for construction after illegal structures sprang up near ASI sites at Khajuraho and Gwalior. This typical bureaucratic tangle must be tackled forthright: the preparation of a comprehensive list of monuments of historical importance would go a long way in resolving this issue. An updated list is also necessary to widen the net of protection. That a multicultural country such as India has only 3,695 monuments worth protecting beggars belief.

New India has posed new challenges in conserving heritage structures. The NMA recently appealed to the ASI to arrange for the removal of two Ganesha idols from the Qutub Minar complex “owing to their disrespectful placement”. The recommendation may have been snubbed by the ASI and even opposed in court. But this reveals a deeper threat — the polarisation of heritage itself. This kind of spurious ideological endeavour seeks to redefine history and national identity within narrow, homogenous parameters, ignoring the pluralist, inclusive tradition — the hallmarks of the Indian ethos — that are preserved in many a heritage site. This infiltration can only be checked by a deeper and spirited public engagement with India’s multiplicity.