I am sitting inside a room watching a grey afternoon full of smog. Occasionally a neighbour with a mask dares to walk out. It is not a winter fog hugging you as you walk around. Smog has a stigma attached to it. It is polluting. The newspapers are full of it, from the piety of a “light” Diwali to Narendra Modi’s advocacy of single-use plastic. Yet, as one reads five full papers of news, in each newspaper one senses the helplessness of governments, both federal and local. Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal makes a show of distributing masks to children and orders the closure of schools. Vijay Goel of the Bharatiya Janata Party sits demonstrating in a mask, accusing Kejriwal and his party of one-upmanship. The statistics are recited mechanically. Politicians hold forth but politics becomes a blame game, where each party pretends an ecological piety of concern that it does not possess. It is clear that everyone has been neglecting the problem. Our folklore says there will be a hypocritical melodrama of concern which will fade away to indifference. Crisis in India does not create tough thinking; we merely try to survive the crisis. What does a citizen do when democracy and governance have no answer to the crisis of pollution?

A psychologist friend of mine reassures me by saying that the responses to pollution and depression are roughly the same. Pollution, he claimed, had an overall visibility that depression does not have. The only indicator for the latter is an act of suicide with a ritual letter protesting loneliness. Everyone mourns the victim, but few go back to reflect on the causes. Pollution and depression behave like mirror inversions of each other, one ecological, the other psychological, one visible, the other literally invisible. Two major problems and we have an illiteracy, a criminality, in governance which is startling. We almost seem to be a society where health does not seem to matter, where suffering is devalued. Worse, Psychology and Ecology are seen as soft subjects, regrettably a bit like Home Science was in the fifties and sixties.

The situation reminds you of the works of the French sociologist, Émile Durkheim. Durkheim talked of two phenomena: of alienation, where one distances oneself from society, and anomie, which is a state of normlessness. Rules exist but don’t matter because somehow values become impotent. Everyday becomes a blip on the radar screen before it disappears. A colleague of mine, an asthmatic, was forced to leave because he was allergic to the city. His situation was so acute that the family and doctors literally bundled him out, dubbing the city one of the asthma capitals of India. His disappearance caused a bit of gossip and then everything returned to normal. There was little reflection on the event. An American professor visiting the city asked me how do children survive? How do we measure the social and the ecological costs of pollution on our children? In fact, our attitude to pollution reminded me of a Kafka story, one of the only anecdotes he wrote on India.

A group of tribes at the end of a forest decided to hold a sacrifice. Elaborate arrangements were made but at full moon, a tiger came and ate the priest. There was commotion but a week later, the village decided to conduct the ritual again. This time, too, the tiger devoured the priest. This happens again and again, creating what we in India call a crisis situation. The villagers decided to hold a meeting. At this gathering, after the usual clichés of conversation, the village idiot intervened. He suggested a solution. He said, ‘Why not make the tiger eating the priest part of the ritual?’ Everydayness returned and life went on, and legend has it that the village idiot later became a World Bank consultant. We routinize new normalcies with great élan, domesticate the October riots, the Bhopal gas tragedy, with a banality and indifference which is appalling. We seem to have banalized the stubble burning Diwali season as another season we have to live through. We treat gang rapes and suicides in a similar manner. Our anger and our anxieties do not last, and we feel life goes on.

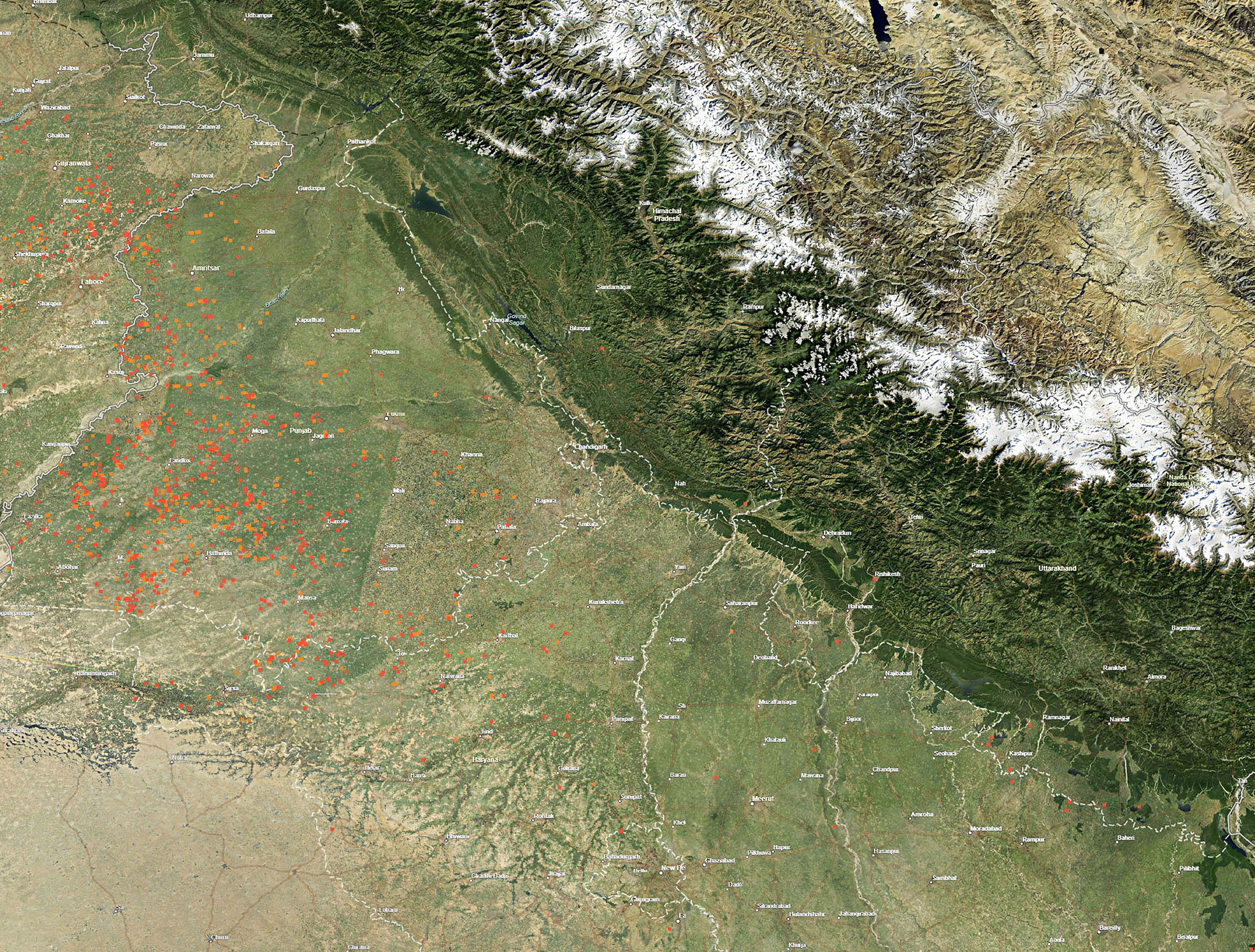

NASA image released on November 19, 2019, shows red dots indicating fires, including those due to stubble burning, in areas surrounding Delhi and the rest of North India. (PTI)

I have seen kids take pills to go to class. When I pointed it out to some of their classmates, they seemed amused. They said most people do it. How do you survive seven hours of boredom? Drugs, at least, punctuate boredom with ecstasy and contentment. Even our authorities are afraid of drugs as a scandal. They blame it on availability, the rise of the high-consumption society, the emptiness of affluence, but no direct action will be taken. Universities bore CSR which has brand names. Wellness societies abound today because the idea of wellness, which needs to be challenged philosophically, skims over the dreariness of depression. The current fashion is to create happiness groups and celebrate happiness epidemics, talk of positive thinking as a technique to nirvana, but never address words like loss, pain and suffering. Language itself sanitizes the everyday violence of our being. We also add a touch of make-believe to it, a sugar coating of liquorice.

When Greta Thunberg became a household name in India, authorities realized that as a phenomenon she spelt trouble. Journalists tried to neutralize her by saying she was naïve about the volume of waste and consumption in Sweden and the United States of America. They portrayed her as a hired hand attacking third world dreams of energy.

The second response is to prop up children, teenagers playing boy scout in ecology, demonstrating we have local Thunbergs. But here again, the projects are trite, and the media prop up a few ecological boy scouts who look harmless, while they do their aspiring parents proud. But the anger of Greta Thunberg at the indifference to pollution and climate change is something we blithely ignored. We do not ask what happens when kids look concerned and behave more maturely than adults. They seem to care for the world which we don’t.

I was wondering how to handle such a situation. It needs an ethics, a moral science — not merely a politics — an ideology challenging caste, class or the State. I was reminded by one of my friends of the moral science books we read in Jesuit schools decades ago. All the textbooks had a brick line covering in blue, green or brown. They were simply produced but beautifully constructed, with spaces for debate, anecdotes for discussion, suggestion about ethical choices and their consequences. They created a forest of stories which taught us ethics, dramatized the subject, especially if you had a teacher with a touch of eloquence or a sense of theatre. The world became alive and meaningful again, and even cricket, as a gentleman’s game, became a playful extension of this moral science class. Words like concern, care, pain and fairness became alive in a different way. It was a fragment of my school education that I treasure.

This fragment of memory set me thinking — we need spaces for ethical experiment, where choices can be discussed, where personal choices and public good can be woven together before they are lived out. Our society needs to create spaces for such everyday drama and debate, which create a literacy and an involvement around ethics. One mistake we have made is in separating ethics and politics, letting ideology sideline ethics. In fact, as M.K. Gandhi suggested, it is the ethical that has to become political. It is time for a civil society of ecologists, human rights activists, academics, concerned parents, to fill in this emptiness between individual choice and public good and show that dissent is a part of everyday life and everyone’s life. More than invoking exemplars from the past, we need to create new exemplars today. There is hope then that next time there is an accident, a suicide, an ecological crisis, one does not turn over the newspaper page in sheer indifference.

The author is an academic associated with Compost Heap, a network pursuing alternative imaginations