The Republic, Plato insisted, could not be the home of the poet. Men of verse, the Greek philosopher was convinced, corrupted the mind.

Had Lucknow been Plato’s ideal State — Politeia — Razi Mohammad would have faced banishment. But Razi, an energetic man with a portly frame, is not a poet. He is a tourist guide who takes visitors around the imposing and intricately planned Bara Imambara. But he can, much like a poet, bewitch — a form of corruption in classical morality — the mind.

On a cold morning, surrounded by a small group of tourists, when Razi began recounting Lucknow’s past standing in a patch of light that filtered in from one of the skylights of that capacious building, it was not difficult for members of his audience — this columnist was among them — to be transported to an imperial era marked by architectural grandeur, opulent recreation, piety, but also the intrigues of Statecraft, ugly politics, deceit and, inevitably, bloodshed. If one paid closer attention to Razi’s stage magician-like chatter, one would notice the sleight of hands indulged in by this master storyteller; he got the names of nawabs mixed up on some occasions, bungled a few dates, and, most noticeably, cloaked myth in the finery of fact.

This predilection for embellishment on the part of the chronicler — guide, balladeer, or poet — has annoyed cerebral minds other than Plato’s. Mehru Jaffer, a scholar and gifted biographer of Lucknow, could be counted among the disenchanted. In A Shadow of the Past, a concise history of this former imperial city, Jaffer blames Lucknow’s endurance as some sort of a Shangri-La on — who else but — the poet.

Yet, the enduring spell of verse cannot be dismissed by the visitor transfixed by Lucknow. The enchanting architecture that survives, be they palaces or havelis, the heady scents lingering in the intestinal lanes of the Chowk, the occasional glimpses of the receding river from the premises of an eerily desolate Chhattar Manzil, memories of the ripples of the purvaiya, the balmy breeze at the hour of dusk — these vignettes are bound to resurrect in the impressionable mind references to the titans of Urdu verse, such as Mir Taqi Mir, who hypnotises the reader with descriptions of Lucknow’s grandeur, and Asrarul Haq Majaz Lakhnawi, who waxes eloquent on the city’s enigma undiminished by time. Indeed, wintry Lucknow shimmered, cocooned in a haze woven, chikankari-like, by poetry.

But to the seasoned eye, the haze is, as Jaffer notes, illusory. It deflects attention from Lucknow’s many warts: economic decline, civic chaos, crimes against women, congested traffic, rash-like urban sprawls, and neglected history.

The legacy of versemen, who prioritised refinement and romanticism, in fact, hides more from the uninformed visitor: such as Lucknow’s riveting literary — progressive — tradition of poetry that served as a political project. A Shadow of the Past unveils poets and periodicals that shone with revolutionary fluorescence in pre-independent India — Moin Ahsan Jazbi, Ali Sardar Jafri, Syed Sibte Hasan, Parcham and Naya Abad, to name a few. A substantial part of this intellectual ferment was brought about by the architects of the Progressive Writers Association such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Mulk Raj Anand, Ismat Chughtai, Saadat Hasan Manto and many other men and women of the arts. Among the latter was Sughra Fatima, whose dual rebellion against politics and patriarchy has been discovered only recently: many more gifted women of verve and verse await a redemption like that of Fatima.

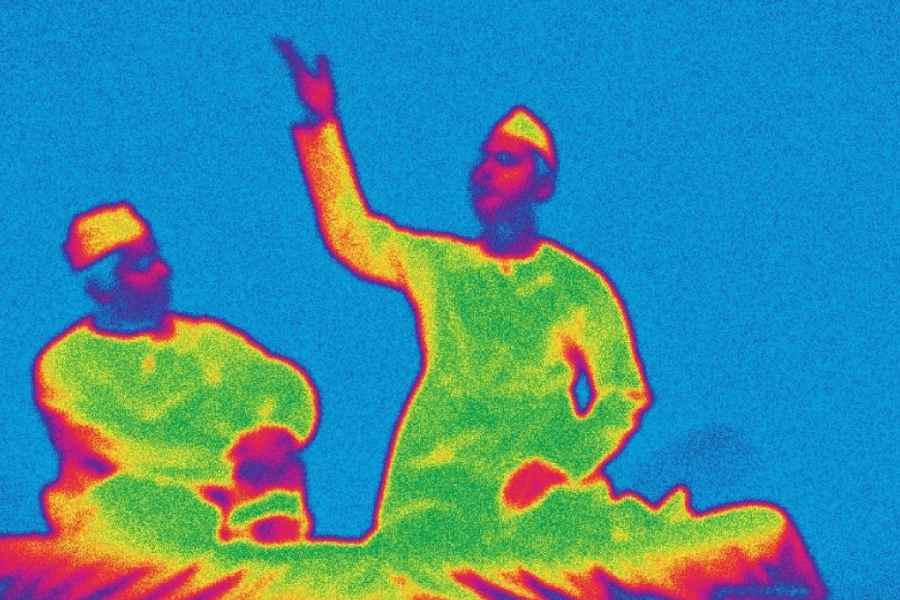

This eclipse of the political by the lyrical and the fantastical in the public discourse on Lucknow’s literary cannons makes Himanshu Bajpai, one of the city’s perceptive minds, ponder. Bajpai’s discomfort with the preponderance of what he describes as the poetry of distraction in Lucknow’s literary registers is interesting. This is because Bajpai, the recipient of a Sahitya Akademi award, is a dexterous practitioner of dastangoi, the medieval art of storytelling, that relies on fantasy as a principal element in its narrative technique. But as a modern, urban storyteller, Bajpai is attempting, with subtlety and ingenuity, to fuse fantasy with contemporary political undertones: this, he believes, is the principal responsibility of an artist. He is aware that this could be construed as an inversion of dastangoi’s original therapeutic purpose: that of turning the mind’s eye away from crises — moral, political, or economic. But he points out that storytelling in its purest form, whether by verse, novel, or dastan, must function as a critical and truthful examination of reality.

The pulls and pressures exerted on performative traditions by the seeming binaries of fact and fiction, embellishment and realism, confrontation and escapism are, of course, not limited to Lucknow’s sites of cultural production. They have been integral to the history of chronicling and its spatial centres — city, village, mohalla — since their inception. But what has made artists like Bajpai acknowledge a renewed urgency to make a choice between being an informed, political performer as opposed to a benign entertainer has been majoritarianism’s intriguing, emerging relationship with and use of both fiction and history. By making the borders porous between the speculative and the empirical, between the concocted and the historically recorded, and, most importantly, by violating the moral compact that encodes what can and cannot be permissible in the art of fictionalising, majoritarianism is demanding a renegotiation with fantasy on the part of the writer/performer and the audience. Incidentally, the cultural ecosystem spawned by Hindutva in today’s India is not the only evidence of bigotry’s fledgling solidarity with fantasy. A recent, intriguing piece in The Economist noted the affection bestowed on fiction/fantasy by the political right-wing in Italy, which, like much of Europe, has witnessed the retreat of liberal politics.

Fiction argues that the end of liberal democracies and liberty or, for that matter, the rise of totalitarianism takes place with the negation of storytelling. Consider Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories where tyranny chokes the voice of the storyteller, the weaver of the dastan.

But the script may vary.

The fate of progressive liberalism can also be decided by the contestation among the tellers of tales; in other words, through a conflict between fantasies. The triumph of one kind of fiction over another — neighbouring Ayodhya’s story has now eclipsed the syncretic tales of Lucknow — heralds new fantasies and newer chroniclers for the Republic.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in