Soon after our tryst with destiny began, we proclaimed ourselves to be equal. Despite B.R. Ambedkar’s scepticism about achieving true equality, the Constitution reflects the moral high ground taken by a people stepping out of long years of subjugation. Since then, young Indians have waxed eloquent about equality before law and India came to take this formal status for granted. As this idea passed into common sense, Indians could even complain that formal equality meant little in the absence of substantive equality. An examination of the concept of citizenship would reveal that citizenship rights of slaves, women and ‘resident aliens’ in the early democracies — the city state of Athens and the Roman Empire — were severely limited.

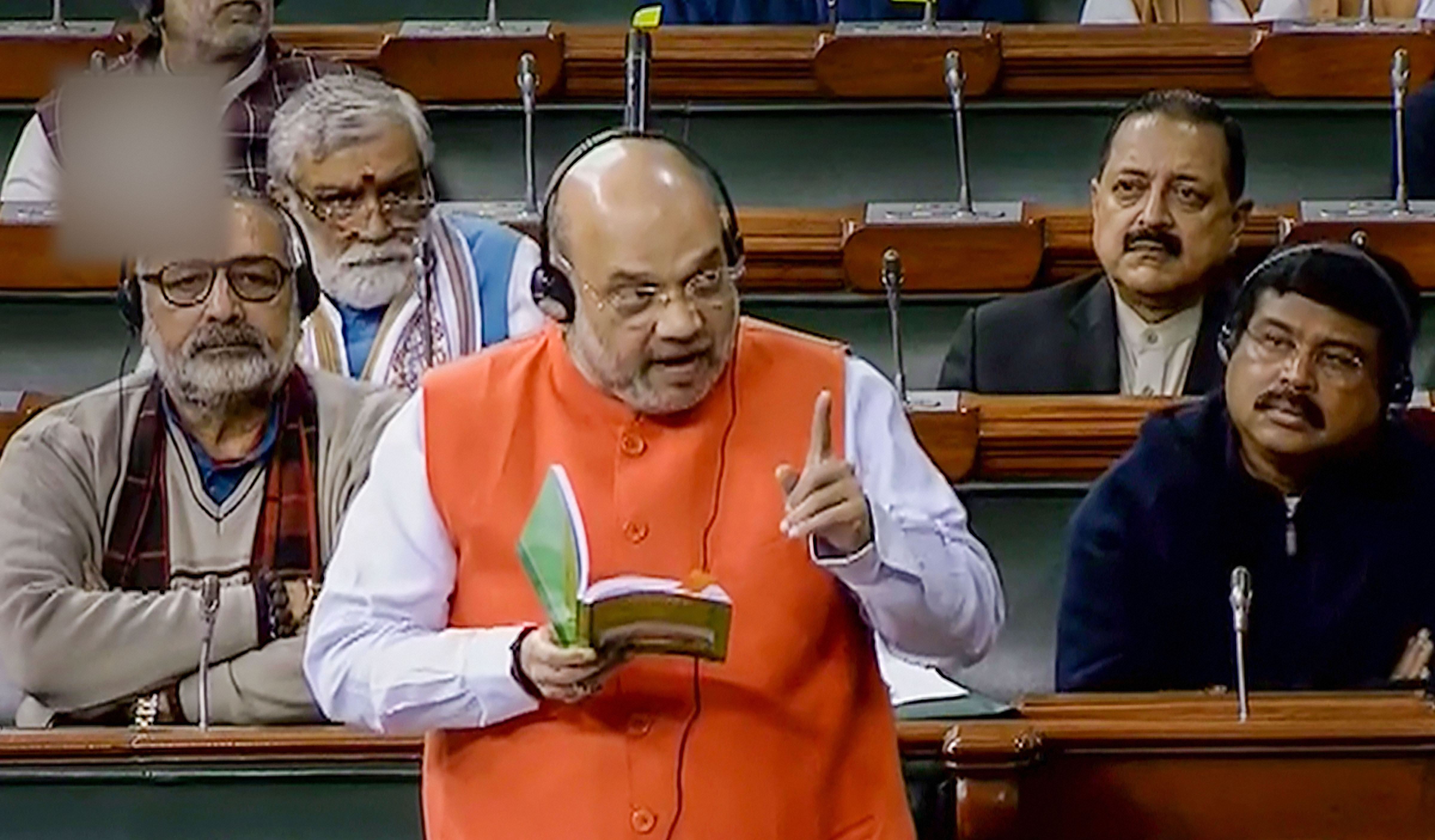

Formal equality before law has been a defining feature of Indian citizenship. This reflects on the civic lives of Indians in two ways. One, it upholds the rule of law, offering protection from discrimination and arbitrary treatment. Two, it reflects the very essence of unity in diversity because without equality, difference would lead to hierarchy and disunity. The proposed amendment to the Citizenship Act, 1955 strikes at the root of these two principles. The Citizenship Act prohibits illegal migrants from acquiring Indian citizenship. The 2019 citizenship (amendment) bill amends this and provides citizenship to Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan by refusing to treat them as illegal migrants.

Amending the Citizenship Act in favour of exclusively named minorities from only these three countries would openly display India’s hostility to South Asian Muslims. It opens a route to making non-Muslim migrants from neighbouring Muslim-majority countries eligible for acquiring Indian citizenship through naturalization even if they had entered India illegally. The present government is raising the spectre of persecution of non-Muslim minorities in Muslim- majority countries in South Asia while the text of the bill makes no mention of religious persecution. Tamil Hindus have been persecuted in Sri Lanka and Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar. These groups are minorities in Buddhist-majority countries. But they are being denied this kindness and courtesy.

The bill violates the right to equality guaranteed to all under Article 14 of the Constitution. The amendments follow from the pre-poll promises of the Bharatiya Janata Party to grant citizenship to Hindu immigrants from Pakistan and Bangladesh. This is accompanied by a simultaneous rhetoric against Bengali-speaking Muslims in Assam as ‘infiltrators’. This bill is meant to be a nod to the Hindu nationalist idea of India as a natural homeland of Hindus.

It bears pointing out that Pakistan has had to define its citizenship within a territorial conception of nationhood even as it recognizes that Muslims are the majority. The negation of Pakistan as a natural homeland of Muslims became conclusive after the creation of Bangladesh. Even at this point, of all the non-Bangla-speaking Muslims residing in East Pakistan requesting repatriation to West Pakistan, only those — other than government employees — born in West Pakistan were accepted. Although Muslims in India are frequently told to go there, Pakistan has not extended any special offers of citizenship to Indian Muslims.

The significance of CAB cannot be overstated. The amendment it proposes to the Citizenship Act, 1955 has made us realize that equal citizenship is not something to be complacent about. Much is being made by commentators about the anxiety among Muslims to being reduced to second-class citizenship. The normative experience of citizenship of Indian Muslims has left a lot to be desired but marginalization, discrimination and violence are well known to the poor, Dalits and women as well. The trouble with the BJP’s rhetoric is that with the National Register of Citizens, the burden of proving citizenship with documentary evidence has been placed on each individual citizen in a country where millions are caught in adverse circumstances to have such documents in their possession. After having fought hard for equality and special protections, if Dalit, women’s and workers’ movements in India fail to oppose the NRC and the CAB robustly, then they would be paving the way for conceding these minimal victories. The complacency being shown by the political parties will cost not only the Muslims but also innumerable other citizens — indeed the country — dearly.

The recurrent breach of the promise of equality before law and the frequent scuttling of the principles of fairness and justice in the workings of all three arms of the State were seen as aberrations that could be corrected. India’s tryst with CAB and NRC will determine if unequal treatment will now assume a formal form and get embedded in citizenship.

Francis Fukuyama declared the end of history because Western liberal democracy had supposedly been honed into a perfect political order that needed no further historical development. In India, we are perhaps witnessing a rebooting of history such that the entire citizenry will be back to square one.