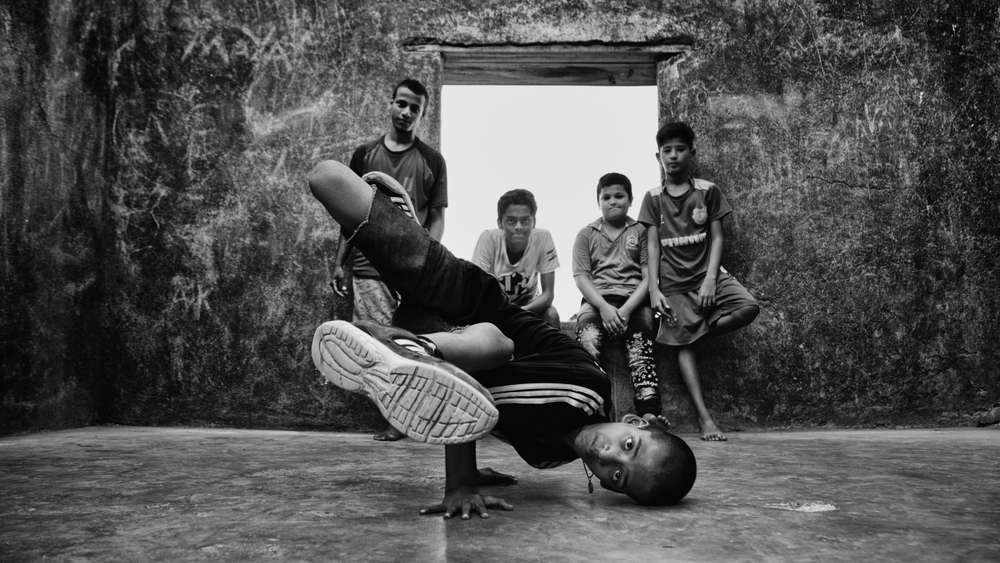

The news that ‘breaking’ — a popular, cynics would hasten to add ‘plebeian’, dance form — is to be added to the itinerary of Olympic sport in Paris four years from now may well be greeted with strange gyrations — the signature moves of breakdancing — on India’s streets. India has always been the proverbial poor cousin in the global family of Olympic medal-winners. It has been 12 years since the country managed to pocket an Olympic gold. Even though it may be a bit too late for the Indian Olympic Association to get Mithun Chakraborty or Prabhu Deva — India’s Dancing Men — to get ready for the Paris Games, the country should not face a dearth of talented men and women with twinkling feet. Even a cursory glance at a bhashan celebration would prove that scores of Indians can make the right moves.

The International Olympic Committee is convinced it is making the right move too. Necessity, as they say, is the mother of invention, and the IOC’s decision has undoubtedly been influenced by the challenge to keep the Olympics relevant to a younger audience with fickle tastes. There is already some concern about modest viewership ratings on account of competition from content on streaming platforms as well as the rising popularity of sporting events within a regional context — the subcontinent’s enchantment with the Indian Premier League is one example. Forced back to the drawing board, the IOC emerged with its ‘Olympic Agenda 2020’, a strategic roadmap that sought to make the Games appealing to modern sensibilities. Breakdance, the IOC deduced, could get the crowds to jive.

This is not to suggest that this truly international competition is breaking new ground for the first time. The history of the Olympics is also a history of the induction of the avant-garde. In the 1900, the Games held, again at Paris — the high citadel of the experimental culture — included an unconventional catalogue featuring cannon firing, fishing, pigeon-racing, kite-flying and fire-fighting. Over the years, other ‘demonstration events’ — the medals awarded in these competitions were not part of the official tally — have included ‘bandy’, a crossbreed of ice and field hockey, and the pesapallo — the Finnish baseball. But games, even the not-so-odd ones, doff their proverbial hat to an invisible hierarchy. That explains why some games make the Olympics cut while others remain as pariah. Netball and squash, in spite of intense lobbying, would not get a ticket to Paris. Golf was part of the 1900 Games, then got booted out, only to be reinducted. These crests and troughs in the journeys of individual Olympic sports reveal their vulnerability to commercial as well as cultural imperatives.

The Olympics also has a tradition of bridging sport and performance arts. ‘The Art Olympics’ — architecture, music, literature, sculpture and painting being the five ‘games’ — were held along with the Summer Olympics from 1918 to 1942. In that sense, breakdance’s inclusion, even though the puritan stiff upper lip would quiver in horror, in the Olympic Hall of Fame represents a continuity and not a divergence, blurring, yet again, the cosmetic border between sport and artistic performance.