If there has been one thing that the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has shown with increasing clarity every passing day, it is the almost total disconnect between the folks sitting on the thrones of power in New Delhi and the ordinary people who put them there. Starting from the exhortation to go out onto their balconies and bang pans and pots (it will be interesting to find out just how many people live in houses with balconies in India), to the clamping of a nationwide lockdown at four hours’ notice (as if all Indians were safely ensconced in their cosy homes as the supreme leader made his emotional appeal via television channels on the night of March 24), to the potentially disastrous decision to turn the whole country into an area of darkness lit only with candles and lamps on April 5 (with the invocation of 9 minutes at 9 pm reeking of the worst kind of superstitious mumbo-jumbo), to the brutally callous treatment of millions of migrant workers, to the attempt to paint the pandemic as a Muslim plot, the list makes for painful reading.

I am tapping this out in a room without electricity, as the tail of Cyclone Amphan rages and roars outside, electric cables have gone down in showers of spectacular sparks, trees — including a majestic shishir that has been part of the topography of our housing estate for at least fifty years — have been uprooted, windows shattered, tin roofs of the shops lining the road outside blown away, and general devastation wrought in the part of city where I live. Things are a lot worse further south (and closer to the Sunderbans), as reports from friends have confirmed, and no one really knows the extent of the damage that will be revealed when the sun rises in a few hours from now. Yet I am able to keep pecking away on my laptop because I have access to several marvels of modern technology: a sturdy machine, with backlit keys and a battery with several hours’ worth of juice, a mobile phone with data connectivity that has enabled me to create a hotspot from where I can gain access to the internet, a roof over my head which won’t collapse, to name just the most obvious.

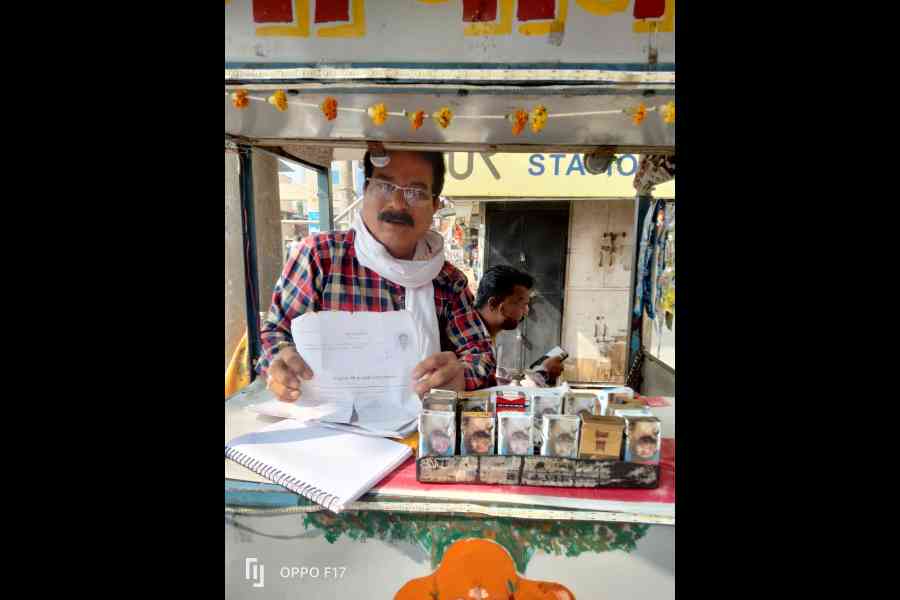

Not one of these things is something that most people in India can take for granted, which is why I am acutely aware of the enormous privilege I enjoy when contrasted to the overwhelming majority of my fellow citizens. Yet, bizarrely and tragically, the powers that be who decide on matters pertaining to education in our country seem oblivious to the fact that most students are simply not as privileged as us — the ones who are supposed to be their guides and mentors. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the touting of ‘online’ classes and examinations as the panacea that will help students overcome the many difficulties they face in accessing education in a situation of lockdown.

There is a fundamental difference between conducting online classes and using electronic/digital means for academic activities, including teaching. The first requires students to be present at a specific time and participate in classes in real time; the latter allows students to download teaching-learning material and communicate with teachers as per their convenience. This must be kept in mind at all times, given the wide diversity of social and economic backgrounds of most students, especially in government-aided institutions of education, such as the one where I am employed. In what follows, I shall confine myself to tertiary education because the problems of school education need a whole separate discussion.

Fortunately, the government of West Bengal, after initially tom-tomming ‘online’ as the solution to all our problems, has now decided against pushing too hard for it, and left it to individual universities to decide on the modalities of how to continue academic activities, interact with students, and conduct assessments. Despite this, many problems remain. A huge number of students are now stuck at home, or in other accommodations, without access to their class notes, books, and other study material (digital or otherwise) that will enable them to do their lessons, leave alone prepare for examinations. Even if we assume, for the sake of argument, that a student has stable, high-speed access to the internet, there can be no guarantee that he/she will be in any way prepared to appear for an event that may well determine the future course of his/her life. Other problems have to do with the chronic overcrowding in practically all our colleges and universities: no one seems to have any idea of how social distancing can be maintained in the rooms in which students sit for classes and, typically, also appear for their examinations. Even if colleges and universities reopen fairly soon, say, by the end of June (a most unlikely prospect, given the continuing rise in Covid-19 cases), how will students commute, given the risk of infection in buses, trains and other modes of public transport? As for those who stay in hostels, it is more than likely that a single case of Covid-19 will lead to the closure of all the hostels of that college or university.

Perhaps we need to look at things from a different perspective, instead of indulging in wishful thinking modelled on the West or predicated on the amenities that only a tiny minority of the economically and socially privileged enjoy. By most realistic estimates, it will be another three to four months at the earliest before we can even think of resuming classes in colleges and universities, and it is likely that there will be a need for further staggered lockdowns if, as the experiences of other places across the world seem to suggest, there is a spike in the number of Covid-19 cases following the opening up of such public institutions. Can we, therefore, think of declaring the current academic session a ‘zero year’ and make provisions so that those who were slated to appear for their examinations in May-June 2020 will do so in 2021? Instances are not lacking. In West Bengal, during the period of Naxalite troubles, colleges and universities deferred examinations by one, or even two, years. Is it too far-fetched to suggest that we can be thinking of something similar given that no one seems to know when we will finally be rid of the Covid-19 scourge or, as seems more likely, learn to live with it? Some may object to this, saying that this will deprive students of a full year of their lives and keep them from joining the jobs that some of them at least have been promised. But potential employers can be negotiated with, and if a ‘zero year’ is followed across the nation, then everyone will be at an equal disadvantage or, if you prefer, advantage. Either way, a zero year appears to make more sense, from the perspective of access and equity, than the rush to conduct terminal semester examinations and push students out of the higher education system — a process that seems specifically designed to favour the economically privileged over their equally talented, but poorer, sisters and brothers.

The author is professor of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, and has been working as a volunteer for a rural development NGO for the last 30 years