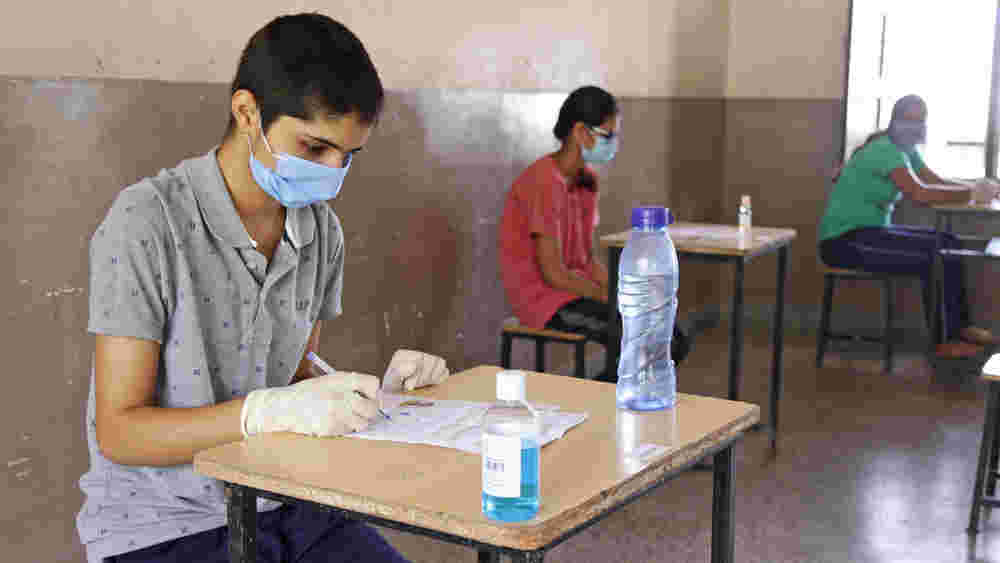

Amidst the pandemic-induced uncertainties, examinations were on the minds of around 10 million students who take the board exams annually. Organizing board exams — many have been cancelled this year — is a mammoth exercise, involving the setting and distribution of question papers, organizing the centres for examinations, invigilation, collection and evaluation of answer scripts, compilation of results and so on. In sum, the board exams could have become a ‘superspreader’. The prolonged uncertainty over the exams adversely affected students, teachers and parents.

Any social or political concern on the discourse of education is limited to examination and evaluation. An examination or an evaluation is not an end in itself; how we use the ‘results’ is what determines the value of examinations. Generally, the results of the senior secondary exams are taken into account for enrolment in higher education programmes. But statistics suggest that only 14-17 per cent of students have access to higher education. This means that around 83 per cent of students have the board exam marksheet as the last certificate of academic qualification on the basis of which they are compelled to make choices about life and livelihood. Most professional institutions — engineering, medical, business administration, law — conduct separate entrance tests for admission. State and Central universities have their own entrance tests or go by the Central Universities Common Entrance Test results. Similarly, the exams for employment are conducted separately by agencies like the School Service Commission, Union Public Service Commission and others. Yet the brouhaha over the board examination results and the examination itself does not subside. Schemes and strategies for alternatives to the examination or evaluation are not uncommon, ranging from open book and online exams to evaluation based on the results of Class XI or internal, online viva-voce. But any alternative needs to be considered on the basis of infrastructural constraints.

The ministry of education should treat the present crisis as an opportunity to rethink and restructure examination and evaluation systems. An examination gets its legitimacy from the role and the function it performs. Examinations help establish meritocracy, a pre-requisite for any democratic society. Meritocracy is generally held to be a social system within which individuals earn rewards and opportunities according to their abilities and efforts. The democratic ideal of individual freedom is linked to the belief of greater agency in a consumerist marketplace. Meritocracy provides motivation for individual achievements that benefit collective progress. Significantly, embedded inequalities in resources are justified under the presumption that everyone has an equal chance of succeeding on the basis of individual merit.

Educational accomplishment and performance are perceived to be key factors in determining merit. Many assume that education improves one’s chances for gainful employment and is, therefore, the most transparent means for social mobility. Some advocates of meritocracy have argued that academic talent is equally distributed throughout the population irrespective of socio-economic status. The truth is that children from families with higher socio-economic status and better repositories of cultural capital are likely to attend better-resourced schools and have access to a wider range of academic support and opportunities. Even within the same district, public schools can offer unequal educational opportunities due to differences in course offerings, the quality of faculty, and the socio- economic background of students. Educational institutions evaluate and certify individual skill, knowledge and efficiency but these performances are always subject to varying cultural values and market interests. For example, most students do not end up with gainful careers and the markets do not acknowledge the norms for merit recognized by conventional centres of learning.

As societies advance, the demand for specialization leads to a preference for those with higher scholastic attainment and greater knowledge. Simultaneously, as industry and manufacturing get replaced by services and advanced technocratic economies, the market for average expertise shifts, resulting in a smaller share of opportunities for the average performers.

Meritocracy, however faulty, is acceptable to a feudal aristocracy or the caste system. However, its success depends on egalitarianism and justice. An innately just system, in turn, depends on unbiased market forces in a society where access to education and employment should be equal. This parity is difficult to achieve because of existing social segregation. Some — not all — have the means to learn how to best navigate the field of play.

Is it then not time to examine the examination and the stultifying evaluation system?

Navneet Sharma is faculty, Department of Education, Central University of Himachal Pradesh