Cassandra, the daughter of Priam — the king of Troy — had a mysterious aura and the gift of prophecy. Cassandra’s prowess to “interpret and communicate the will of the gods” was a boon from Apollo. She had foreseen soldiers hiding inside a wooden horse left outside the gates of Troy. She even foresaw her own death. But Apollo’s gift to Cassandra was also a curse. Although Cassandra had agreed to pledge herself to Apollo in exchange for this invaluable blessing, she later spurned his advances. As punishment, Apollo spat into her mouth and swore that she would never again be believed by anyone. The phrase, ‘Curse of Cassandra’, was thus born and has since been cited to describe prescient warnings about everything, from environmental disasters to market crashes.

During the late 1990s, everyone on Wall Street poured money into dotcom stocks, believing incomparable riches were waiting to be made. Everybody except for one: Warren Buffett. He invited the wrath of many for his gloomy commentary and ominous warnings of “a bubble about to burst”. Investors promptly dubbed him the ‘Wall Street Cassandra’. The markets eventually crashed and Buffett’s credibility was restored.

The ‘Wall Street Cassandra’ during the 2008 global financial crisis was Michael Burry. His expertise was in spotting the perilous fault lines underpinning the subprime market. The message he conveyed was one of impending apocalypse. Raghuram Rajan, the chief economist of the International Monetary Fund in 2005, had warned that financial instruments like credit default swaps had made the market riskier. The perceptive insights of Burry and Rajan would turn out to be the early predictors of what eventually became the biggest financial crisis in seven decades. In contrast to those investors who heard but dismissed Buffett’s forewarnings, Burry’s and Rajan’s prophecies were simply not heard.

In the age of Covid-19, we’re now recognizing the Cassandras who had warned us about the contagion. A decade and half ago, the epidemiologist, Larry Brilliant, alerted the world about the catastrophic effects of pathogens. He predicted that a billion people would get infected and imagined global depression and jobs lost. Sound familiar? In 2005, the epidemiologist, Michael Osterholm, wrote, “This is a critical point in history. Time is running out to prepare for the next pandemic.” In 2017, he reiterated this message in his book, Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs. In 2018, the virologist and flu expert, Robert Webster, predicted an imminent flu pandemic when he wrote: “Nature will eventually again challenge mankind with an equivalent of the 1918 influenza virus.”

But talk and action are like chalk and cheese.

The three countries with the highest number of deaths from Covid-19 so far are the United States of America, Brazil and the United Kingdom.

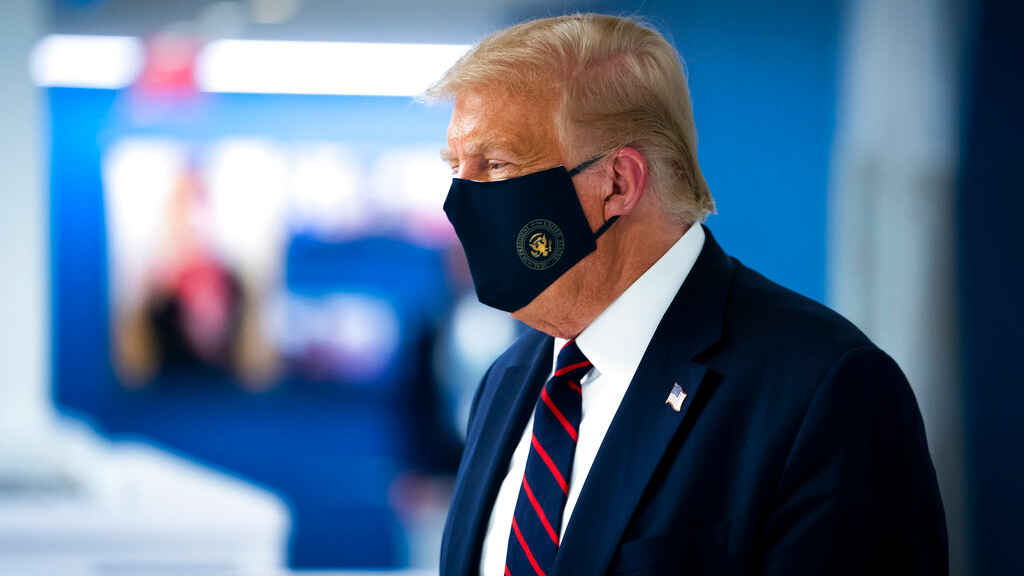

Donald Trump embodied King Priam — the emperor who pooh-poohed Cassandra’s prophecies. In March, he had said, ‘You’ll have packed churches all over during Easter.’ Later, he wanted to revive the economy to help his re-election prospects. The Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, called the virus “just a little flu” and repeatedly disobeyed medical advice, mingling in crowds without a face mask and shaking hands. In March, Number 10’s scientific advisers warned that the British government should advise people not to shake hands; the same day, Prime Minister Boris Johnson boasted about shaking hands “with everybody” at a hospital with confirmed coronavirus patients. Bolsonaro and Johnson were subsequently infected. What do these three leaders have in common? Their dismissal of the threat squandered precious time when their government should have been scaling up tests, isolating early cases, and mobilizing the response teams.

Legend has it that when a messenger arrived to inform Tigranes the Great, King of Armenia, that forces under the Roman consul, Lucullus, were on their way, Tigranes reacted by beheading the messenger. One can only assume that any subsequent information relayed was more positive. The phrase, ‘Don’t shoot the messenger’, had an uncanny resonance when recent news reports revealed that high-profile personalities from the coronavirus task force, including Anthony Fauci, arguably the most trusted man in the US, have been unable to obtain the White House’s permission to appear on television. In 2017, the media had claimed that Trump was presented with a twice-daily ego-boosting dossier filled with flattering photos and positive stories about him. Unlike the messengers in Tigranes’s palace who would clamour to avoid being the bearer of bad news, one wonders whether officials in the Trump White House jostle to be selected as the one to deliver positive news to their master.

Aeschylus wrote in Agamemnon, “Things are now as they are; they will be fulfilled in what is fated; neither burnt sacrifice nor libation of offerings without fire will soothe intense anger away.” Many would-be prophets professing to know the future continue to emerge as the pandemic rages. As predictions pile up, we now recognize that over the past decade we failed to listen to multiple warnings.

Who are the Cassandras of this moment? What would it entail to heed their advice?

The author is a Harvard alumnus and works for an investment bank in Mumbai. He is also a member of the Young Scholars Initiative at the Institute for New Economic Thinking, founded by George Soros et al.