Kshama virasya bhushanam (Forgiveness bejewels courage) is an ancient Sanskrit aphorism. It is cited less in our times than it used to be. Today the gold standard for courage is musculature.

In the year 1959, Jawaharlal Nehru had been prime minister of India, its first, for twelve years and E.M.S. Namboodiripad, chief minister of Kerala, its first, for just over two. After a so-called ‘direct action’ organised against the new government triggered by its radical land reforms and education policies, Nehru was led to conclude that the EMS-led communist government of that state should be dismissed. Dismissed? Yes, that is right. And, calling the EMS government “an astonishing failure”, he did have it dismissed, using Article 356 of the Constitution of India.

EMS’ government was, in point of fact, the first non-Congress government to have taken office — after the general elections of 1957 — in the whole country. The world, not just India, was struck by the democratically delicious irony of a communist government having been elected to office, peacefully, emphatically, through a free and fair election, defeating India’s party of the freedom struggle, the party that was ruling India and all the other states of the Union, led by one whom everyone acknowledged to be the rosebud in the arbour of the world’s democrats, Nehru.

Kerala, with its high literacy and virile press, electing a communist government had made news, big news as something of a ‘first’. But not everyone celebrated. Understandably, conservatives and the religious orthodoxies in Kerala did not. And no less understandably, India-watchers in US’s ruling establishment did not either. ‘Alarm bells’, it is said, rang in Washington when Kerala’s democratic choice of communism came to be known.

EMS’ ministry was compact, with eleven members: C. Achutha Menon, a seasoned communist lawyer as finance minister, Joseph Mundassery, a Malayalam littérateur as education minister, and V.R. Krishna Iyer, the brilliant lawyer and legal activist, as law minister. And it had set about doing some pioneering things, audacious things, exactly as Nehru’s Congress government at the Centre was doing, in its own style.

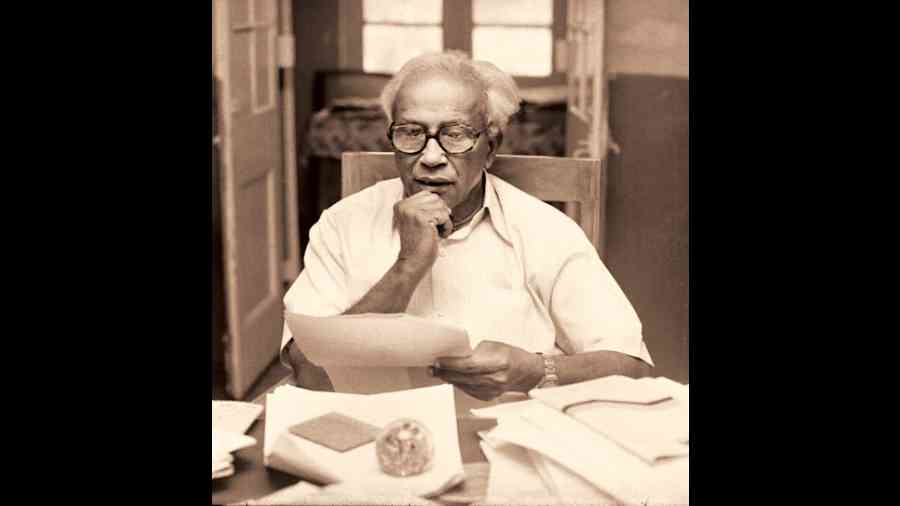

Agatha Christie’s first murder mystery is called The Mysterious Affair at Styles, the last word being a noun, referring to a house in England. What happened in Kerala during the movement against EMS’ government was essentially about styles, about the way that may be adopted for introducing progressive reforms and overcoming entrenched resistance to them. What happened was also pretty mysterious and ended in what may be termed the constitutional extermination of the 1957 election result for Kerala. But this column is not about that mystery and its grim ending. It is about the man who emerged from it in its lead role — E.M.S. Namboodiripad (EMS, for short), the 25th anniversary of whose death occurs today.

That year — 1959 — was, for EMS, a landmark year. Born in 1909, he was fifty — in his prime as the first chief minister of his newly-born state. That year — 1959 — was for Nehru a landmark year too. Born in 1889, he was seventy — as the first prime minister of new India. Did EMS nurse and show deep resentment at what had been done to undo his election, his chief ministership? Of course, he did. Who would not? But there is such a thing as grace, as civility, as plain decency.

The Times of India brought out that year a handsome volume of tributes to Nehru on his seventieth birthday. There is no finer publication on that remarkable man than that book, containing articles — all freshly written — by world leaders and national ones, compilations of vintage photographs and cartoons by TOI’s peerless caricaturist, R.K. Laxman. One of the articles in it is by the justsacked EMS.

He starts by placing a handicap on his own path: “’Would you call Prime Minister Nehru’s Government an astonishing failure, as he called your Government of Kerala in a recent statement?’ — this was one of the questions that was put to me by a journalist at a press conference held in Delhi after the Communist Ministry had been dismissed. I did not answer that question for several reasons, one of these being that it would be wrong to make such over-simplified assessments of a government that has several achievements to its credit.”

He then lists, with brevity and precision, three of these achievements. First, in the international sphere, Nehru’s role in creating the ‘Bandung Spirit’ (non-alignment). Second, in the development sphere, Nehru’s lead in the formulation of India’s Five Year Plans. Third, in the sphere of the nation’s personality, Nehru’s emphasis on the secular character of the State.

This three-point praise was, in table-tennis parlance, EMS’ equivalent of an elegant service by tossing the ball upward without any spin. And this was to be followed by his striking the ball on its descent real hard and real targeted so that it first touches his (the server’s) court in a personal reference and then lands smashingly on the receiver’s court in a devastating critique.

“How is it possible,” he asks, “for one to ignore all these… when one sees them in contrast to the medievalism, obscurantism and ideological backwardness shown by the leaders of certain other newly independent but under-developed countries ?” — the ball has been tossed up without a spin in a ping-pong display of kshama virasya bhushanam.

“… it would be difficult,” he writes, “to refrain from a reference to the recent developments in Kerala” — the ball is on its descent.

“I would not dwell at great length on the unconstitutionality either of the ‘direct action’ organised from below by the Congress, or of Central intervention” — the ball is level with his raised racket.

“I would only point out here how dangerous a precedent this can become in other States and under different circumstances” — the ball has landed on the receiver’s court emphatically.

Nehru was, in a very essential sense, a historian. So was, I submit, EMS. He says further down the essay: “Our Indian Constitution cannot, by any means, be called more democratic or republican in spirit than, say, the Weimar Constitution of the post-First World War Germany. And, it was under the Weimar Constitution that Hitler was allowed to establish his ‘open-terror dictatorship’.”

The time that EMS wrote this piece was the time when Nehru’s prime ministership seemed irreplaceable. He writes in what, again using table-tennis analogy, may be called his smash: “The question ‘After Nehru What?’ which is on everybody’s lips today is, therefore, a magnificent tribute to Nehru’s incomparable role in India’s political framework as much as a regrettable commentary on the inner rot of the Congress machinery.”

Inner rot is no party’s monopoly today.

As the twenty-fifth anniversary of EMS’ death coincides with the seventy-fifth anniversary of our Independence and moves towards that of the Republic, all state governments, including that of Pinarayi Vijayan, the CPI(M) chief minister of Kerala, the Union government, and all leaders of political parties should heed EMS’ warning about the inner rot that power games generate.