Narendra Modi has a tremendous sense of theatre. Listening to him on Friday morning unfolding yet another masterstroke to rally the despondent, I happened to look over the balcony railing just in time to see a chauffeur from one of the other flats spit noisily into the middle of the paved drive before climbing into his master’s expensive limousine.

The crudeness of Indian reality and its contrast with Western theory may not be known to the professionals who think up the most poignant gestures. But remembering the controversy over the origins of Neil Armstrong’s first words on setting foot on the moon — “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” — and the many suggested sources, one cannot but wonder if the authors of tomorrow’s symbolic gesture to dispel the darkness were not unconsciously aware of Bishop Latimer’s deathless last words, “Be of good cheer, master Ridley, and play the man; we shall this day light such a candle in England, as I hope, by God’s grace, shall never be put out.”

Both prelates were burning to death when one tried to comfort the other. They had no afterwards to think of, only the hereafter. Here, it’s the afterward that is most worrying. Poetry inspires faith in Tagore’s promise to light “my lamp... and never debate if it will help to remove the darkness” but it becomes difficult to sustain faith when a gobble of spit shoots out from a neighbour’s mouth. Pictures of those historic five minutes of fervent applause, of blowing conch shells and clanging plates, pierced here and there by the shrill ululation of devotional ritual, showed balconies packed with the faithful. Where had the insistence on social distance disappeared?

Social distance is now a universal catchphrase. It’s captured in the ancient Hindu obligation that lingers in concepts like ento and jootha, signifying unclean in a ritual sense that doesn’t exclude the physical. There is no English equivalent. I like to think that a modern variant was devised by a great-great-aunt, a childless widow, who once accompanied her Anglicized Civilian brother and his Brahmo family on a holiday to Simultala. She had her own separate kitchen in the sprawling villa so that maintaining a distance, social or anti-social, presented no difficulty. It was different when they were picnicking by the gurgling Nilabaran river. As a breeze picked up, my grandmother, who would have been one hundred and forty this year, remembered her aunt — the childless widow I am speaking of — frantically urging them to move away with their unclean food and vessels because the grass carried contamination. Her original Bengali is much more vivid.

There is a sense of that in Advaita Malla Barman’s Titash Ekti Nadir Naam, which I have read only in Kalpana Bardhan’s translation. As the young fisherman, Kishore, refuses a bigger piece of fish “as vehemently as he can, she [the hostess] cleverly touches the bowl audibly to his plate, so that Kishore now will have to eat it, as it cannot be served to someone else and will go to waste otherwise.” It had become ento, violating the crucial gap of social distance. I ran into that predisposition once in a sweet shop by unthinkingly placing my sal leaf plate of singara on the glass counter. A howl of protest from the opposite corner of the shop prompted the counter assistant to suggest I use the window ledge.

I moved away at once but how do Calcutta’s thousands of pavement eateries that serve rice, dal, egg curry and varieties of what passes for ‘chow’ to millions of workers maintain social distance? Mumbai’s Dharavi slum alone doesn’t cram humanity together; such is the lifestyle of the country. The problem rears up in even more fearsome guise at the prospect of business being resumed and public transport catering again to millions of workers, students and others. India has been suspended in an artificial limbo since March 25. Sooner or later, it must again pick up the threads of life and work. The community infection that the authorities now proudly deny will become inevitable in the sweaty congestion of buses and trains.

That is why the hysteria of TV channels over the March 13-15 gathering at a Nizamuddin West mosque in New Delhi seems so contrived. Without the government’s nod and a wink, perhaps more, the TV channels would not suddenly have woken up a fortnight later to the supposed perils they didn’t even think worthy of reporting at the time. Of course, it is the media’s duty to explore and assess any possible medical threat. But as Mamata Banerjee stressed when she denounced the uproar as ‘communalization’, the Union health secretary had affirmed on March 13 that “there is no epidemic of Covid-19 in the country.” Why then the belated hullabaloo? Although the Shaheen Bagh and other protests against a misunderstood Citizenship (Amendment) Act were provocative and unjustified, anything that smacks of an official communal agenda would be worse, making mockery of India’s mammoth effort to counter the pandemic.

It’s a truism to repeat that the poor suffer most. Space and time are luxuries that not many can afford. Instead of being kicked around — literally — by a power-drunk petty bureaucracy, the streams of home-bound migrant labourers should either be accommodated in transit camps or sent home in the fleets of trucks and lorries at the command of the paramilitary and military forces. In fact, now is the time to inject meaning into that phrase beloved of politicians — ‘on a war footing’. Humanity demands that the military be authorized to take charge of feeding, clothing, housing and transporting workers whose labour is indispensable to the economy.

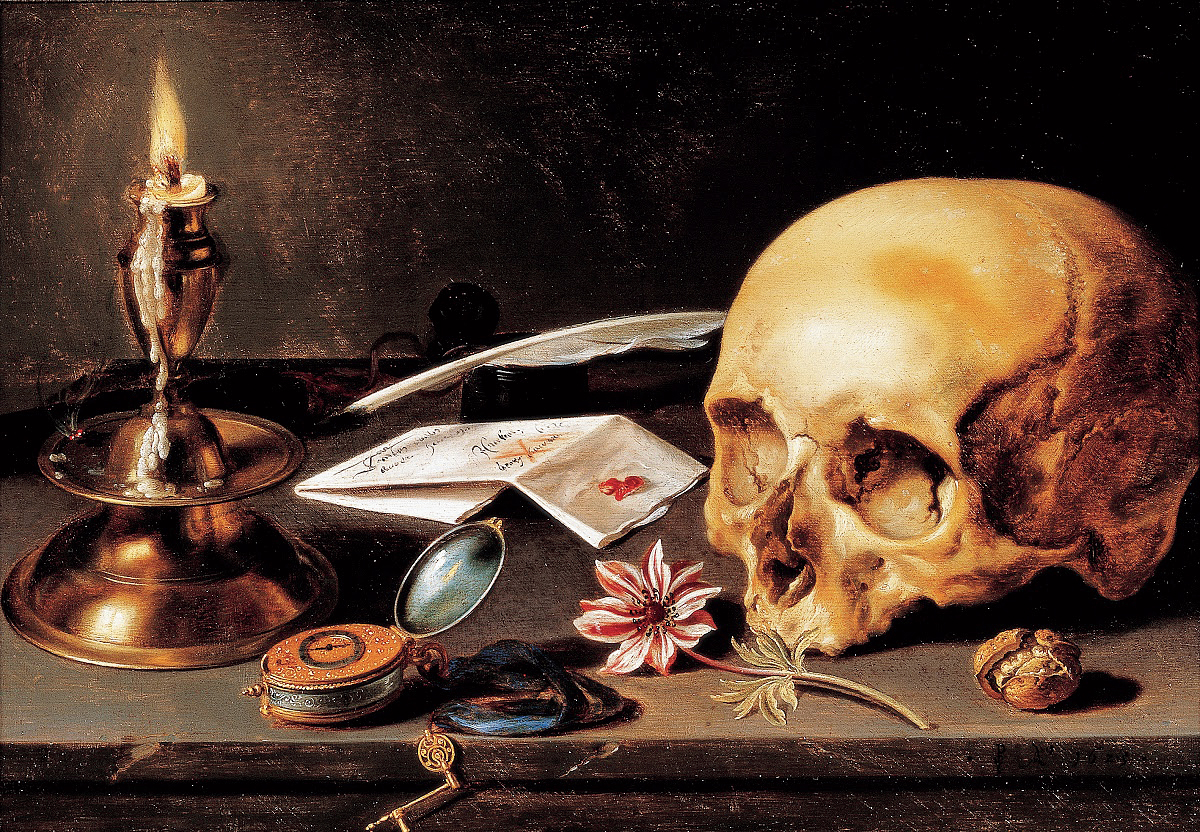

The Covid-19 pandemic invites comparison with the Black Death — bubonic plague — that struck England in a series of massive eruptions from 1331 right up to 1750. The plague, which also originated in China, was a local affliction. Covid-19 is global. Five thousand miles and nearly 700 years separate them. The link is the young shoot of hope. One saved England, the other could change the world. A new and recognizably better and healthier London emerged when the final echoes of the doleful call of “Bring out your dead!” that Samuel Pepys, the diarist, noted had died away.

Although the Great Fire of London ruined many merchants and property owners, there rose after it an English renaissance in the arts and sciences. Attempts had already been made to prepare for post-plague reconstruction by limiting the number of lodgers a family could take, and instilling a sense of civic pride by making householders clean the streets outside their property while State-employed scavengers cleared the worst of the mess. London was largely rebuilt over the next 10 years. The new streets were wider. Pavements flanked them. Open sewers were abolished, wooden buildings and overhanging gables banned. Brick or stone were mandatory and design and construction were regulated. Having overcome adversity, Londoners had a greater sense of community and confidence.

As Czech medical supplies land in Madrid, Cuban doctors help Italians, 20,000 doctors and nurses flock to Britain’s much-maligned National Health Service and the World Health Organization compliments India for eradicating polio and smallpox, there is every reason to hope that this ordeal will also leave mankind with a greater understanding of interdependence. The Elysium where “no infected individual can find another individual to infect” to quote Partha P. Majumder, president of the Indian Academy of Sciences, in this newspaper will remain elusive so long as driving swanky cars goes hand in hand with indiscriminate spitting. Beyond the vaccine, India needs better housing, improved public transport, effective sanitation, modern medicare and caring governance far more than public relations gimmicks and political agendas. For now, we live with the awareness that the worst is yet to come.