After a resounding electoral mandate, the narrative of the habitual dissenters invariably changes. The theory that caste would be the most formidable defence against majoritarianism collapsed in a heap by the afternoon of May 23; the elaborate conviction that contemporary India has got over its earlier fixation with stability and prefers patchwork coalitions that reflect the federal impulse has also taken a battering; also punctured was the self-serving conspiracy theory that the introduction of a paper trail would inevitably expose the vulnerability of the electronic voting machines and pave the way for the return of paper ballots.

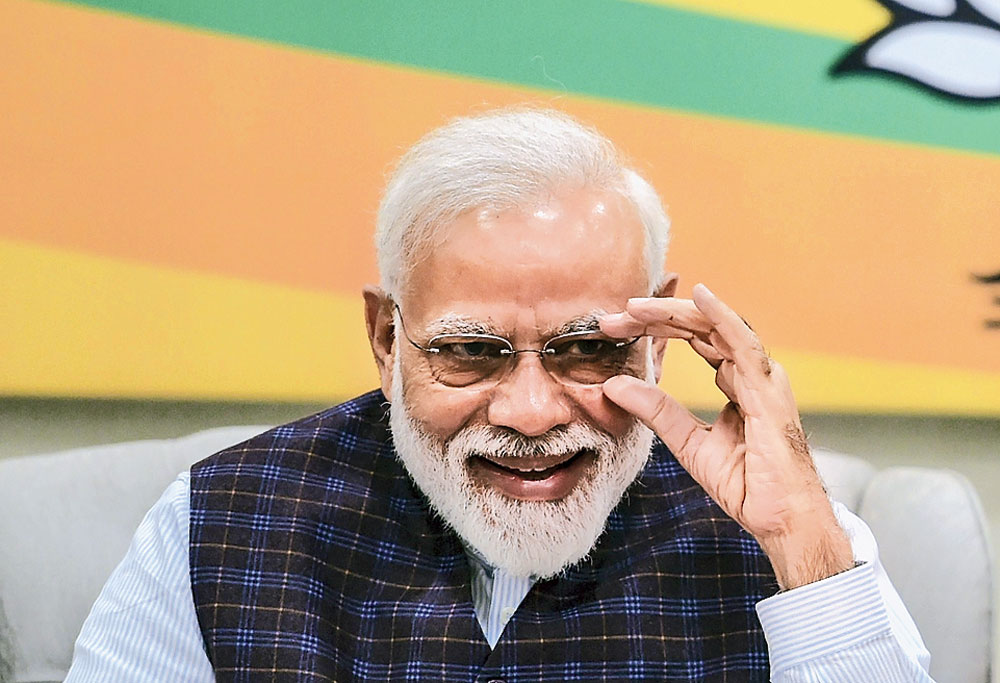

However, certain theories have a habit of lingering on, thanks in no small measure to the comfort they provide to their proponents. In this session of Parliament, the chattering classes were stirred from their deep depression by a feisty intervention of a new member from West Bengal. In a brief intervention that attracted the attention of the English language media, the MP identified — with the help of a poster on sale at Washington’s Holocaust Museum — seven symptoms of fascism that were discernible in the India of Narendra Modi.

Fascism is a loaded term, a term that may have originated with Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, but which has been suitably modified to signify anything that is perceived to be disagreeable. Anything which does not connote niceness — the ideal of contemporary liberal thought — is, by implication, fascist. It is also cross-cultural and wonderfully multinational. A recent issue of a left-wing fortnightly published from Chennai, for example, has a very long interview with an academic that argues that every country gets the fascism its deserves. This seemingly profound observation was accompanied by the quiet admission that while there are fascist tendencies in the increasingly Hindu-ized polity, the ruling dispensation sees no compelling need to smash and abolish the liberal framework that was constructed by the Constitution in 1950.

This, however, is an unfashionable position. It is far more eye-catching to equate the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh with Hitler’s Brown Shirts — Italian fascism never gets more than a passing mention because of its sheer incompetence — and Modi’s captivating oratory with Hitler’s demagoguery. What grab the eyeballs are suggestions that the lumpen gangs of beef vigilantes that specialize in terrorizing Muslim meat traders are somehow as sinister as the SS guards of a concentration camp. What adds to the offence is the fact that surgical strikes against a country that nurtures terrorists and secessionists are greeted with euphoric flag-waving celebrations that leave their mark on electoral outcomes. Didn’t Hitler, they ask, rise to power using the democratic route?

The latest version of fascism-search focuses on the subversion of institutions. It is claimed that important institutions of the country — the Election Commission, the Comptroller and Auditor General and even the judiciary — have become compliant arms of a saffron executive led by India’s own version of Hitler. An appendage of this identification of compromised institutions is the claim that the general election was won on the strength of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s formidable control over the media. The media, it is claimed, has shed all pretensions of fearless independence and is today a nationalist cheerleader for the saffron forces. It too belongs to the camp of those who sold out.

Most Indian readers and TV viewers who are often quite exasperated by the shrillness of competing points of view during studio discussions would probably find this assertion ridiculously overstated. There may be a lot of things wrong with the Indian media — print and web-based and electronic. These are the stuff of everyday conversations, quite understandably so, because — as with cricket — nearly every middle-class individual has a view on how the media should conduct itself. However, even while there are allegations of bias against individual publications, portals and channels, it is hardly the case that people are bereft of choice. Indeed, with smartphones adding another dimension, it may well be said that India as a country is over-exposed to the media, perhaps even more than many of the democracies in the West. Almost every taste is catered to and at a ridiculously affordable price.

The 2019 general election was a test of media freedom. The campaign was covered exhaustively by the entire media to the point of exasperation. Almost every speech of the two main campaigners — Prime Minister Modi and the (then) Congress president, Rahul Gandhi — was covered, often through live telecasts. In addition, the other stalwarts, ranging from the BJP president, Amit Shah, to chief ministers of the regional parties, received considerable attention. There was no attempt to black out either the Congress’s ‘Chowkidar Chor Hai’ utterances or Modi’s snide asides against the naamdars of the world. There were opinion polls and exit polls, and individuals chipped in with their there-is-no-wave conclusions. Every journalist with a keyboard or a microphone made his or her assessments of constituencies, regions, states and country and there were spirited exchanges on television. The unofficial WhatsApp network had its own narratives, and conspiracy theories and fake news too did the rounds. Everyone sold their wares and at the end of the day the voters made their decision. I believe that it was, under the circumstances, an informed choice and certainly far more informed than the time when campaigning was a local matter and access to media limited.

That is why the suggestion by an organization that India ranks 140 out of 180 in press freedom — ahead of Pakistan, North Korea, China, Russia and Turkey but below Myanmar, the United Arab Emirates and the Western democracies — strikes me as being odd and highly subjective. The sheer scale of the media in India and the fact that it is a growth industry would suggest that the environment for its growth is real. Yet, this dodgy ranking has become the basis for a belief that the media is somehow ‘controlled’ by political rulers.

Earlier this month, I attended a conference on media freedom in London jointly hosted by the foreign ministries of Canada and the United Kingdom. India wasn’t directly assailed for snuffing out the free media — unlike Myanmar, Russia and even Bangladesh — but there were endless snide comments, mainly centred on Modi — a figure journalists feel should be hated. Mainstream journalists also hate President Donald Trump with a passionate reciprocity of feeling. However, hatred of Trump does not necessarily extend to the conviction that media freedom in the United States of America is under threat.

After the conference, I returned with the conviction that the threats to media freedom in India are highlighted for the consumption of Western monitoring organizations that love to believe this is how third world countries behave. India, of course, is no longer third world, although it isn’t the high-cost first world either. It is a country where market economics — that is what drives the market leaders — coexists uneasily with a media that operates as an instrument of extortion and even blackmail. Local journalists are often threatened by the local political neta; infrequently they are even murdered. But the reasons aren’t always gloriously noble.

That’s because the media in India is itself driven by different compulsions, ranging from honest profit to promoting political parties and plain trading on information. It is the traders who feel threatened and beleaguered by the Modi government’s indifference to the principle that government must court media. They see it as fascism and broadcast it as such, thereby fuelling Western gullibility. So much so that a journalist of modest insignificance claimed to have been offered political asylum by a UN official because he dared to call out the sangh parivar’s fascism at an international conference.

It’s a shame he didn’t take up the offer and trigger a new media downgrade of India.